Statement on Management Accounting

Key Principles of Eective

Financial Planning and Analysis

About IMA

®

(Institute of Management Accountants)

IMA, named 2017 and 2018 Professional Body of the Year by The

Accountant/International Accounting Bulletin, is one of the largest

and most respected associations focused exclusively on advancing the

management accounting profession. Globally, IMA supports the profession

through research, the CMA

®

(Certied Management Accountant) program,

continuing education, networking, and advocacy of the highest ethical

business practices. IMA has a global network of more than 125,000

members in 140 countries and 300 professional and student chapters.

Headquartered in Montvale, N.J., USA, IMA provides localized services

through its four global regions: The Americas, Asia/Pacic, Europe, and

Middle East/India. For more information about IMA, please visit

www.imanet.org.

Statements on Management Accounting

SMAs present IMA’s position on best practices in management accounting.

These authoritative monographs cover the broad range of issues encountered

in practice.

© July 2019

Institute of Management Accountants

10 Paragon Drive, Suite 1

Montvale, NJ, 07645

www.imanet.org/thought_leadership

About the Authors

Lawrence Serven is an internationally recognized authority on enterprise performance

management (EPM). He is the author of Value Planning: The New Approach to Building Value

Every Day (J. Wiley & Sons) and is the founder and former CEO of XLerant, Inc., a leading EPM

software company. He can be reached at (203) 977-3856 or lawr[email protected].

Kip Krumwiede, Ph.D., CMA, CSCA, CPA, is the director of research for IMA. Prior to joining

IMA, Kip was a management accounting professor and also worked for two Fortune 500

companies. Kip has published numerous articles in both practice and academic journals. He can

be reached at (201) 474-1732 or [email protected]g.

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ............................................................................................ 3

Introduction ..................................................................................................... 3

Scope ............................................................................................................ 5

Does FP&A Matter? ............................................................................................ 5

Identifying Best- and Worst-Performing Organizations .................................................... 6

The 12 Principles of FP&A Used by Best-Run Companies ................................................. 6

Fundamental Principles – Building a Firm Foundation ....................................................................7

Principle 1: Develop a strategic long-range plan and identify specic initiatives and

projects/plans to execute it. ................................................................................. 7

Principle 2: Identify resources needed to implement projects/plans and put them in

the budget. ....................................................................................................8

Principle 3: Understand how operational plans will drive nancial results and monitor

progress of those plans. ......................................................................................9

Principle 4: Quickly identify the business reasons behind plan-to-actual nancial variances. ........9

Principle 5: Make course adjustments when falling behind on nancial or operational goals. ..........9

Accountability Principles – Building a Culture of Accountability .....................................10

Principle 6: Cascade both nancial and nonnancial operational targets down the

organization to more specic targets. ..................................................................... 10

Principle 7: Hold people accountable for delivering nancial results and link to

nancial incentives. .......................................................................................... 11

Principle 8: Hold people accountable for delivering operational results and link to

nancial incentives. .......................................................................................... 12

Advanced Principles – Taking FP&A to the Next Level ................................................12

Principle 9: Identify what drives business success and develop key performance

indicators (KPIs) for those drivers. ......................................................................... 12

Principle 10: Establish long-term and short-term targets for the KPIs. ................................ 13

Principle 11: Develop initiatives and operational projects to achieve KPI targets. ................... 13

Principle 12: Monitor results of KPIs and link to nancial incentives. .................................. 13

Key Principles of Eective Financial Planning

and Analysis

Table of Contents (continued)

Support for the 12 Principles ................................................................................14

The People Side of FP&A .................................................................................................................. 14

Understanding the Underlying Business...................................................................... 14

Building Effective Working Relationships Outside of Finance and Accounting ......................... 15

Understanding the Specic Area or Department They Are Supporting .................................. 15

Communication Skills ........................................................................................... 16

Technical Skills ................................................................................................... 16

Key Competencies .............................................................................................. 17

Selling the Value of Improved FP&A Practices to Top Management ....................................17

Step 1. Decide to measure the benets of better FP&A. ................................................... 18

Step 2. Dene the measures and collect data. .............................................................. 18

Step 3. Calculate the net value of improved FP&A. ......................................................... 20

Step 4. Rene and evaluate measurement process. ........................................................ 20

The Role of Technology in FP&A .............................................................................21

Where to Start .................................................................................................22

Conclusions .....................................................................................................23

Figures and Tables

Figure 1: What is FP&A? .........................................................................................4

Table 1: Summary of the 12 Key Principles of Effective FP&A ..............................................7

Table 2: Guidelines to Help Identify FP&A Technology Enablers .......................................... 21

Appendixes

Appendix 1: Survey Demographics and Results ............................................................. 24

Appendix 2: Developing an ROI for an FP&A Improvement Initiative .................................... 29

Appendix 3: Assessment of FP&A Practices ................................................................. 30

Further Reading ...............................................................................................33

Glossary of Terms ..............................................................................................34

Key Principles of Eective Financial Planning

and Analysis

3

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Executive Summary

Financial planning and analysis (FP&A) is a decision-making platform that includes reporting

and analysis, planning and budgeting, forecasting, and nancial modeling, and is a big part of

the management accounting body of knowledge. This SMA provides the principles of effective

FP&A organized into 12 principles and how to prioritize them, and details what the best-run

organizations do differently with FP&A. It also discusses the role of technology, the competencies

needed, how to get started, and how to “sell” the need for FP&A improvement to top

management. Appendix 1 provides survey evidence supporting the 12 principles.

In general, the best-performing organizations take a more rigorous approach to FP&A:

• They have tightly integrated all the components of FP&A.

• They have merged operational and nancial planning.

• They track progress of initiatives designed to improve the operational numbers just as

closely as they monitor nancial results.

• They hold people accountable for delivering results, including linking pay with

performance.

• They translate strategy into action and make sure initiatives are properly resourced

and accounted for in the budget.

• They are agile enough to make course adjustments when they identify the need.

Introduction

Financial planning and analysis (FP&A) is a decision-making platform that includes reporting

and analysis, planning and budgeting, forecasting, and nancial modeling. FP&A is a big part

of the management accounting body of knowledge as represented in the IMA Management

Accounting Competency Framework.

1

Few processes within the purview of a CFO have so

much potential to create—or destroy—business value than FP&A. How a company allocates its

resources will impact its success or its failure. Even if an organization has the right strategy, if

the budget does not reect those priorities and properly fund tangible initiatives, the strategy

will likely not succeed. Beyond money, if people are not actually spending their time executing

the plan, it simply will not happen. Executing the plan requires that people know what the plan

is and their role in executing it. While aspects of FP&A may seem routine, such as budgeting or

monthly variance reporting, they are all links in the chain of the value creation process.

(See Figure 1.)

Unfortunately, many companies are not achieving the full potential of their FP&A activities.

A study by American Productivity & Quality Center (APQC) found that just 40% of nance

executives from large organizations rated their FP&A as effective.

2

Two-thirds of the executives

1

IMA Management Accounting Competency Framework, April 2019, bit.ly/309rjw8.

2

Mary Driscoll, “Why is Financial Planning and Analysis Falling Flat?” CFO.com, March 19, 2015, bit.ly/2JA8cq0.

4

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

said that their nance teams are too busy doing basic nancial management duties such as

periodic forecasting and actual-vs.-budget analysis. KPMG has published a report suggesting that

it is the “nancial” in nancial planning and analysis that reduces the effectiveness of the FP&A

function. Too much focus on forecasting and budgeting within a scal year with an emphasis on

meeting short-term targets takes time away from the “planning and analysis” that is needed to

help the company develop and execute its strategy.

3

Add to that the evolving socioeconomic

and competitive issues that companies now face—shifting geopolitics, regulatory environment,

consumers’ shrinking wealth, increasing global competition, rate of business failures, and

technology revolutions—FP&A teams must not only analyze the past business environment but

also somehow integrate the changing global landscape into their analysis.

4

This SMA discusses principles and execution of effective FP&A practices, organized

into 12 principles, and how to prioritize them. It details what the best-run organizations do

differently with FP&A and also discusses the role of technology, needed competencies of the

people facilitating the process, suggestions for how to get started, and ways to persuade

top management of the need for FP&A improvements. Appendix 1 provides survey evidence

supporting the 12 principles.

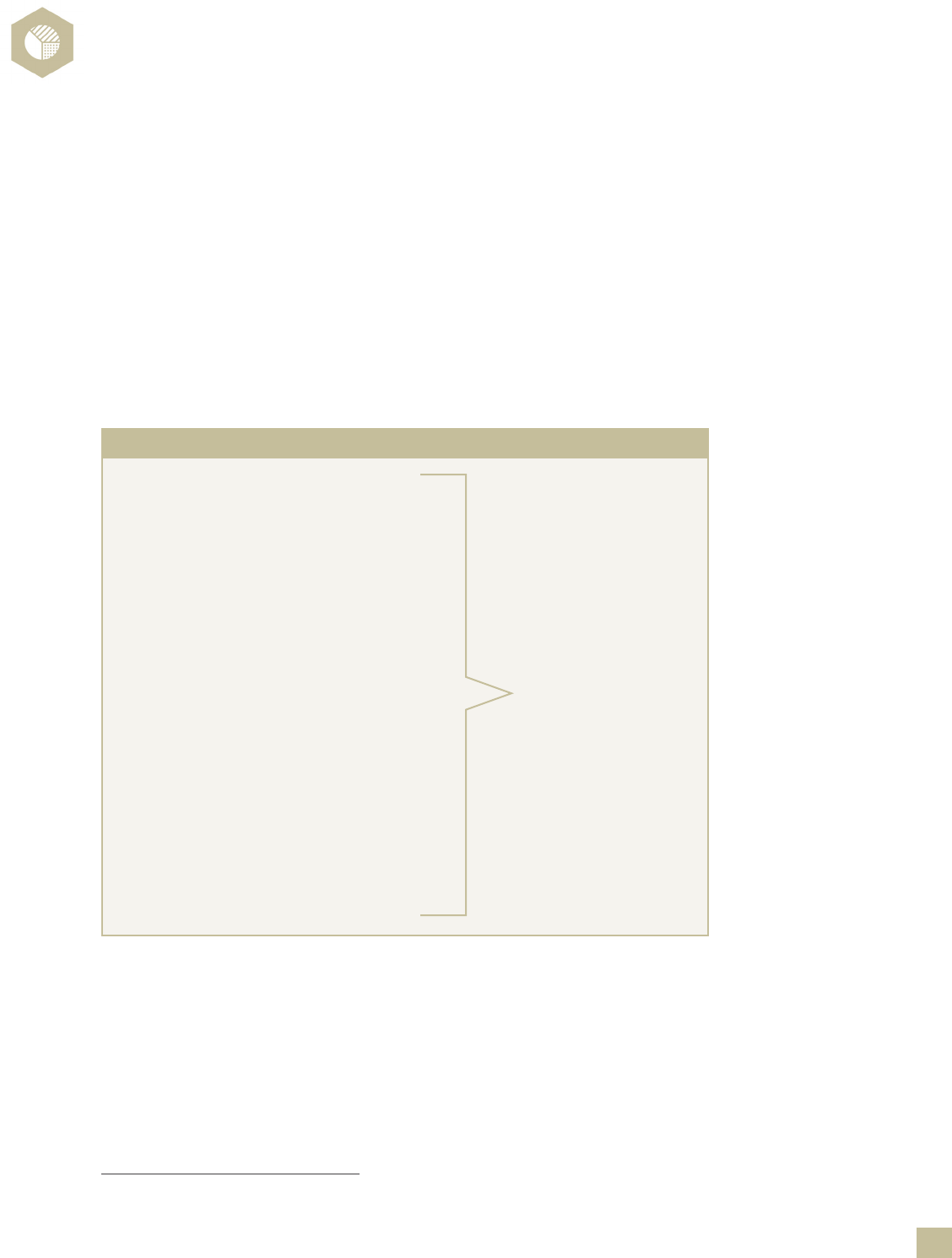

Reporting and Analysis

3 Operational reporting

3 Financial reporting

3 KPIs

3 Dashboards

3 Variance analysis

3 Drill through/roll up/drill across

Planning and Budgeting

3 Annual operating plan (AOP)

3 Budgets

3 Head count planning

3 Long-range planning

Forecasting

3 Rolling forecasts

3 Trend analysis

3 Predictive analytics

Financial Modeling

3 What-if analysis

3 Scenario analysis

Figure 1: What Is FP&A?

FP&A IS A

DECISION-

MAKING

PLATFORM

3

David McCann, “Why you should take the ’F’ out of FP&A,” CFO.com, September 28, 2017, bit.ly/2M6wmdX.

4

Kasthuri V. Henry, “The FP&A Squad: Financial Agents for Change,” Strategic Finance, April 2012, pp. 37-43,

bit.ly/2VYpymY.

5

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Scope

As illustrated in Figure 1, this SMA denes FP&A to include reporting and analysis, planning and

budgeting, forecasting, and nancial modeling. FP&A goes beyond traditional budgeting and

forecasting and focuses on planning and execution. Forecasting and budgeting are certainly

important, especially in communicating to the organization if it is on track to achieve its business

outcomes or to raise warning ags. But forecasting results is not the same as building a plan to

actually achieve them. Planning and execution are what will determine success.

This SMA is primarily addressed to nancial and management accounting professionals

and executives involved in any aspect of FP&A, from analyst to CEO. It is not an examination

of specic forecast modeling techniques or an assessment of methodologies like zero-based

budgeting. It focuses on the underlying core principles driving successful FP&A. Unfortunately,

many of today’s popular FP&A methodologies (such as rolling forecasts, zero-based budgeting,

and beyond budgeting) usually bypass these core principles or implicitly assume they are already

in place.

Does FP&A Matter?

The value that FP&A delivers to an organization depends on how well it is performed. If done

well, it has the potential to drive shareholder and stakeholder value by:

• Driving planning and execution of the strategy.

• Better management of expenses and risk analysis.

• Generating ideas for new business opportunities.

• Ensuring the optimal allocation of resources (how time and money will be invested for

maximum results).

The concept of variability underlies risk management and FP&A concepts. Risk can be

dened as uncertainty where at least some of the possibilities involve a loss, catastrophe, or

other undesirable outcome.

5

Thus, the degree of uncertainty of each aspect of the business

must be considered and may determine the expected variances between actual and budget.

Expected protability for relatively stable industries, such as equipment leasing and universities,

is more predictable than for other more dynamic industries, like technology and construction.

Thus, there is a greater need for strong FP&A wherever there is greater uncertainty.

On the other side, poor FP&A can lead to undesirable outcomes:

• Waste of the organization’s resources (time and money).

• Reduced chance that nancial and operational goals will be achieved.

• Increased likelihood that departments will act at cross purposes.

• Reduced chance that the strategy will be properly executed.

• Continued deals with lower to no protability.

5

Douglas W. Hubbard, How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of “Intangibles” in Business, Third Edition, Wiley,

Hoboken, N.J., 2014.

6

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

A controller with a poor-performing company in the media and entertainment industry

summarized the consequences of poor FP&A: “Increased chance of misallocation of resources,

difculty analyzing the performance of the company due to misaligned or lack of proper

parameters, and increased chance of corruption and collusion leading to undetected fraud.”

Those companies that have experienced the downside of poorly run FP&A are probably less

likely to want to invest more time and attention to it. But the consequence can be a downward

spiral. Poor FP&A leads to less time and resources invested in it, which leads to a further erosion

of condence, performance, and results. Rather than stay with the status quo, take advantage of

FP&A to create value and consider the core principles, practices, and action items discussed here.

Identifying Best- and Worst-Performing Organizations

Many of the observations, quotes, and recommendations proffered in this report are based on a

research study developed by comparing the survey results of respondents working in best- and

worst-performing organizations. To identify best-performing enterprises, we chose organizations

that reported they (1) consistently meet or exceed the targets they set for themselves as a

company/institution and (2) consistently meet or exceed the results of their competitors. It is

important to note that both criteria are met, not just one or the other. Admittedly, this method

of classication has limitations, but this criteria represent what virtually every CEO is trying to

achieve. The results of the research study are contained in Appendix 1.

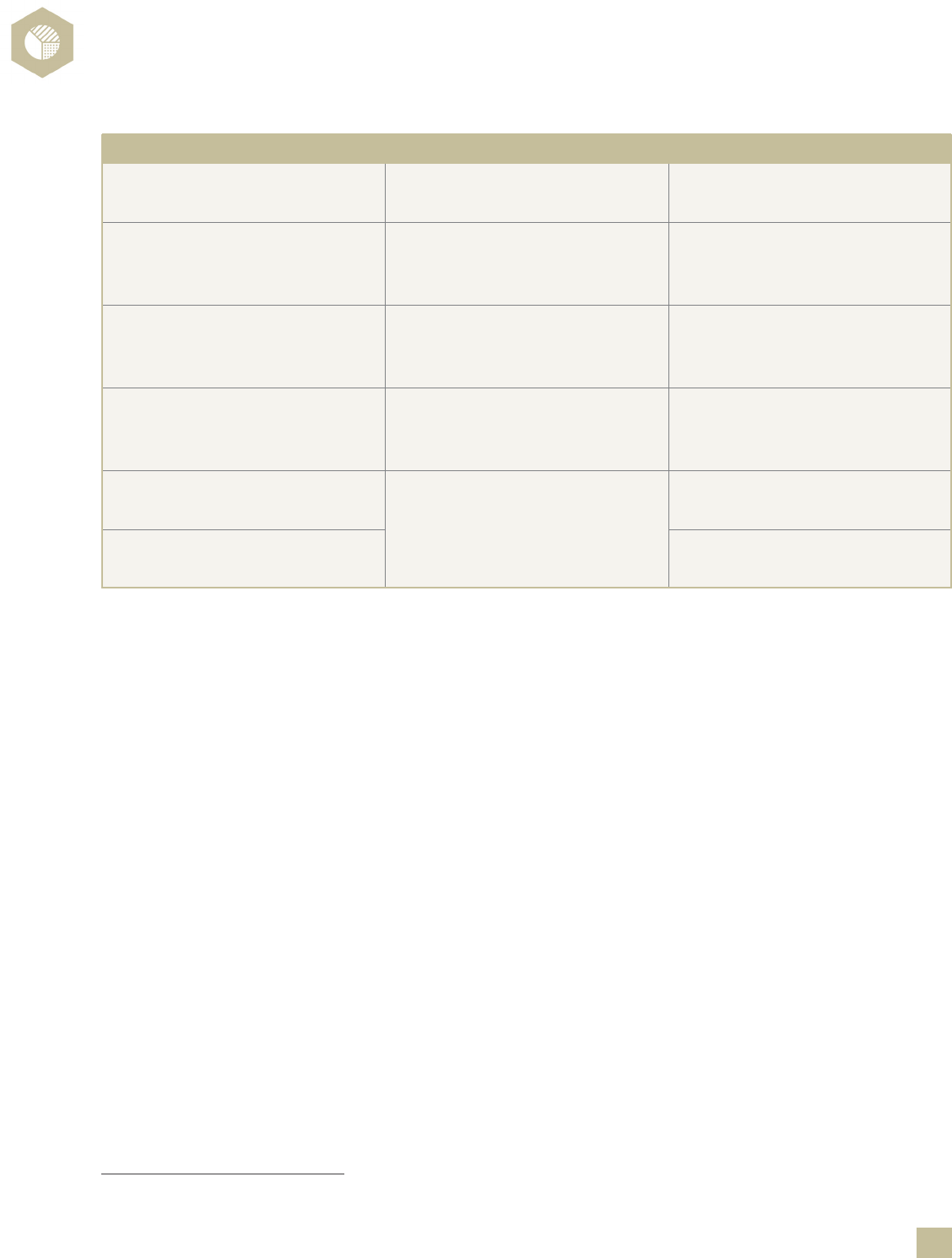

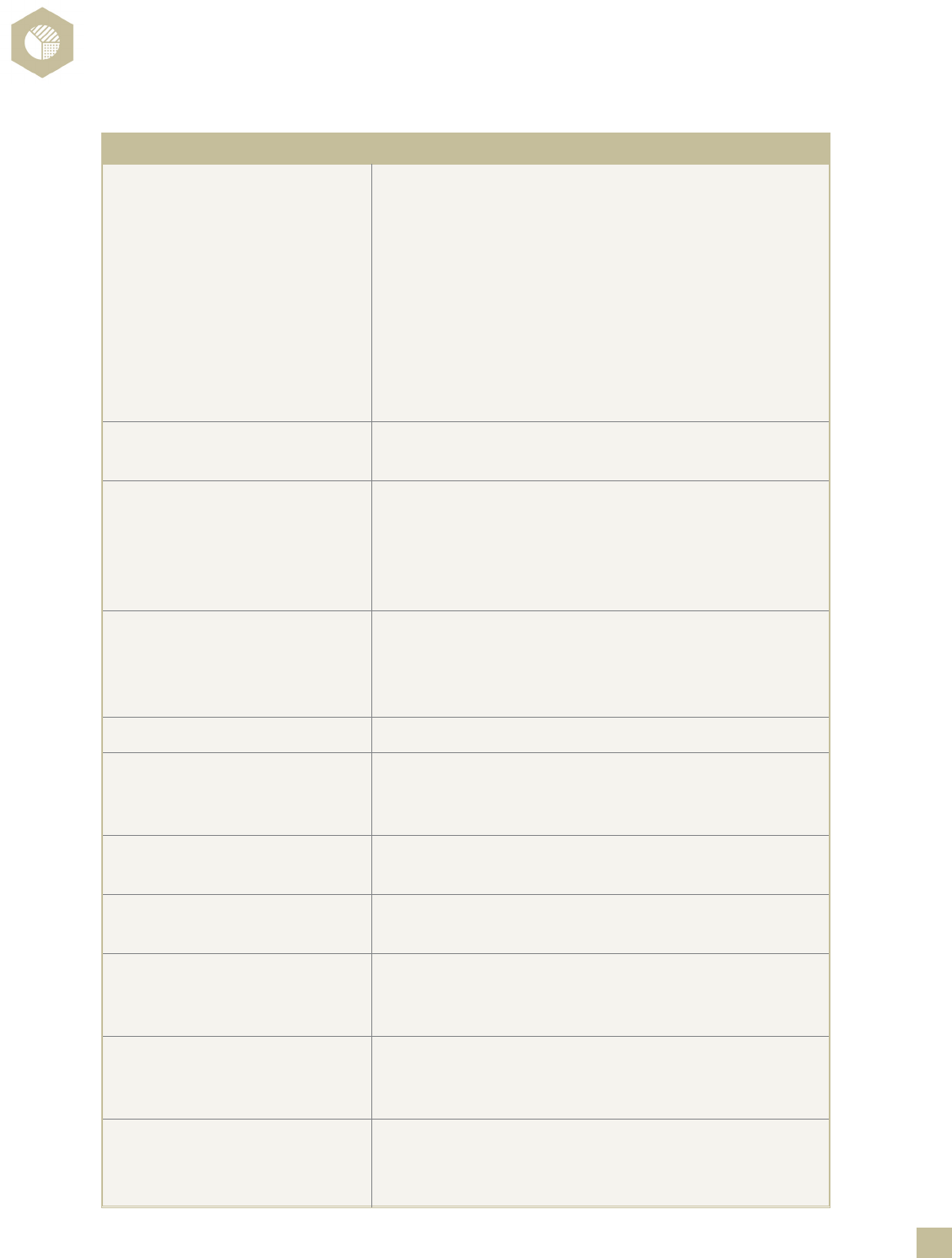

The 12 Principles of Effective FP&A Used by Best-Run Companies

This SMA discusses and recommends 12 key principles of FP&A best practices. While any one

principle, if properly implemented, will likely yield positive results, it is the way these principles

reinforce each other that will more fully deliver on the promise of effective FP&A. Of course,

determining an FP&A improvement road map includes tailoring the key principles to meet the

unique current circumstances and state of FP&A in the organization.

Many organizations may say, “We sort of do these principles today.” But that is not really

the test. The real test is how well the principle has been deployed and with what type of rigor

and discipline. Beyond that, the bigger question to answer is: How integrated are the principles

as a whole system? Table 1 presents a summary of the 12 key principles of effective FP&A.

7

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Fundamental Principles – Building a Firm Foundation

The rst ve principles are designed to provide a rm foundation for FP&A. They encompass

translating strategy into actionable plans, making sure those plans are properly resourced,

consciously linking operational performance and nancial results, quickly identifying variances and

the reasons behind them, and making course adjustments. These principles, if properly executed

and adhered to, should get an organization started down the path of effective FP&A practices.

Principle 1: Develop a strategic long-range plan and identify specic initiatives and

projects/plans to execute it.

Every company or institution has its own way of creating a strategy. A complete discussion

of determining strategic priorities and execution is beyond the scope of this SMA.

6

Strategic

planning should be anchored to the organization’s mission, vision, and core values. It typically

begins with a scan of the external environment using a framework such as Porter’s Five Forces,

followed by a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis. A gap analysis is

performed with respect to where an organization wants to go compared to its current position.

Based on these analyses, organizational goals are set and initiatives are put in place. We will

begin at the point where an effective strategy has been developed. If an organization is not at

that point, it should work on that rst.

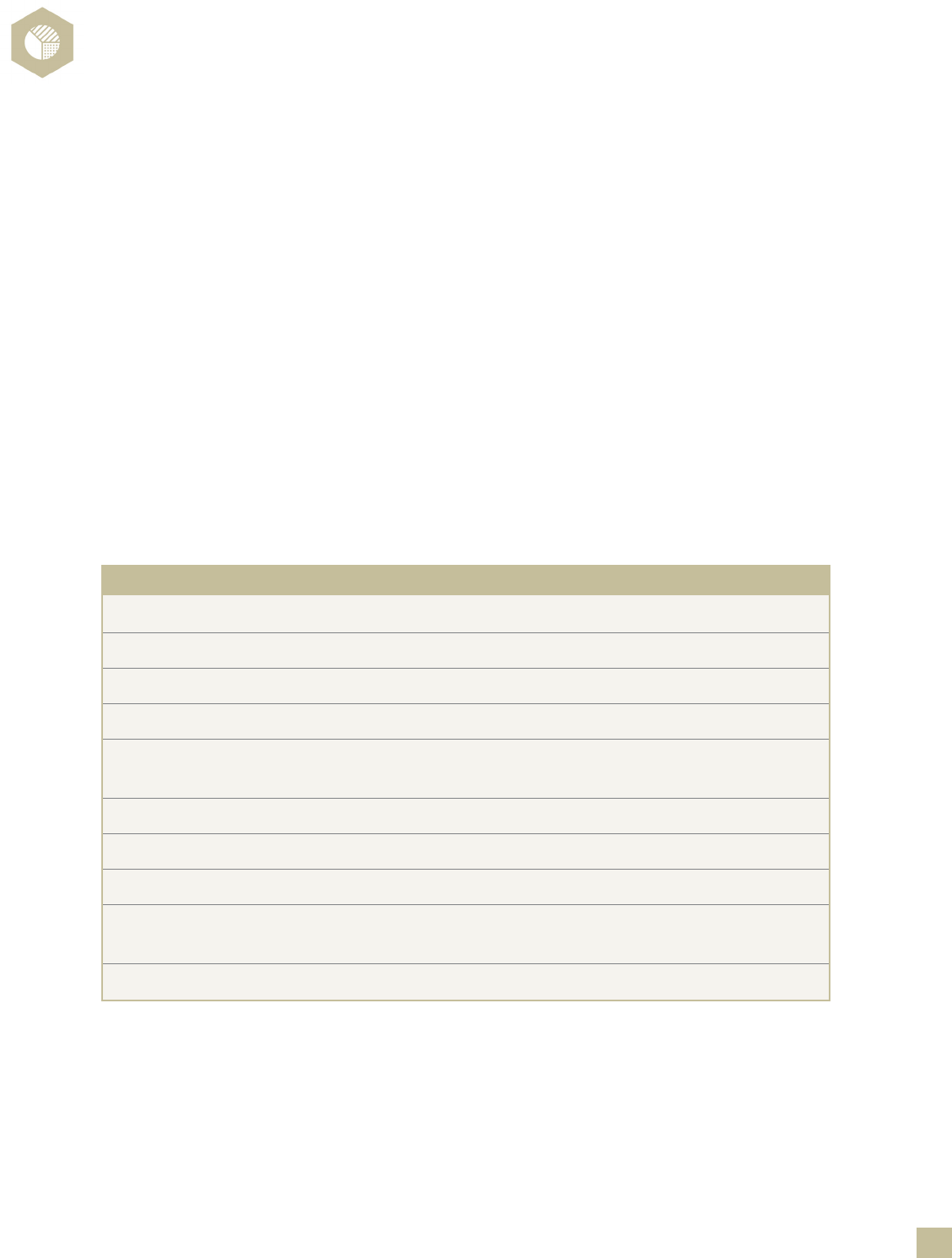

Fundamental Principles –

Building a Firm Foundation

P1: Develop a strategic long-range plan and

identify specic initiatives and projects/

plans to execute it.

P2: Identify resources needed to implement

projects/plans and put them in the

budget.

P3: Understand how operational plans will

drive nancial results and monitor

progress of those plans.

P4: Quickly identify the business reasons

behind plan-to-actual nancial variances.

P5: Make course adjustments when falling

behind on nancial or operational goals.

Accountability Principles –

Building a Culture of Accountability

P6: Cascade both nancial and nonnancial

operational targets down the organization

to more specic targets.

P7: Hold people accountable for delivering

nancial results and link to nancial

incentives.

P8: Hold people accountable for delivering

operational results and link to nancial

incentives.

Advanced Principles – Taking FP&A

to the Next Level

P9: Identify what drives business success

and develop key performance indicators

(KPIs) for those drivers.

P10: Establish long-term and shorter-term

targets for the KPIs.

P11: Develop initiatives and operational

projects to achieve KPI targets

P12: Monitor results of KPIs and link to

nancial incentives.

Table 1: Summary of the 12 Key Principles of Effective FP&A

6

For an excellent reference on strategy planning and competitive analysis, see HBR’s 10 Must Reads on Strategy,

Harvard Business Review Press, Boston, Mass., 2011; a great way to develop these skills is IMA’s CSCA

®

(Certied in

Strategy and Competitive Analysis) Learning Series and certication, available at www.imanet.org/csca-credential.

8

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Whatever the strategy, the best-run companies:

• Have a long-range plan with a differentiation strategy (such as a cost leader).

• Identify specic initiatives to achieve the strategic plan (for example, continuous

improvement initiative, reducing scrap and defective products to reduce waste, and

launching a new product.

• Translate those specic initiatives into shorter-term operational projects that can be

executed over the coming scal year (for example, streamlining the delivery process,

Six Sigma, and root cause analysis).

This principle makes a difference in an organization’s success. A customer support

professional from a small “best-performing” chemical facility in the Middle East commented,

“Effective FP&A can help management to measure the protability of transactions through any

level of projects, per customer, per sector, per product, or per line of production, to nd more

than one alternative to improve the protability.” On the other side, an internal auditor from a

“worst-performing” media and entertainment company said, “FP&A should be more connected

in terms of dealing with different divisions/departments and more involved and aggressive in

terms of communicating the nancial impacts of each operational project, especially if the plan is

misaligned from the beginning.”

Principle 2: Identify resources needed to implement projects/plans and put them in

the budget.

Many well-conceived projects that could in fact drive the desired outcomes of the plan do not

come to fruition. The most common reason is insufcient resources, including both money and

people’s time. This happens when those people developing or leading these projects fail to

identify the specic resources needed to do the project. Instead they say, “We will just do it.”

Another common pitfall is that the budgeting process is often disconnected from

the strategic planning process. Management may develop great plans during a retreat and

“commit” to a project. But it is during the budget process when real decisions about the

allocation of resources actually get made. The best-performing organizations:

• Identify the resources (money and people) needed to execute the operational projects

that will drive results (such as investment in new technology to improve the processing

time, consulting fees related to design and implementation, and staff time required).

• Incorporate those resource requirements into the budget.

A respondent from a best-performing manufacturing company commented, “[FP&A]

effectively motivates resource management applications, putting both nancial and human

resources in the right place and in the right amounts.” Another said, “Effective FP&A can guide

the efcient usage of limited resources in the best way possible. [It] can control the behavior of

approving parties to have a mind-set of evaluate and analyze rather than approve only.”

9

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Principle 3: Understand how operational plans will drive nancial results and monitor

progress of those plans.

The best-performing organizations know that operational decisions and actions will impact their

nancial results. What is different is that these organizations make those connections explicit:

They clearly understand how their operational projects will impact their nancial results, and they

monitor the progress of those projects.

Typically, there is a monthly review process that compares nancial performance to

planned performance. But that monthly review process should also include an update on key

projects to make sure they are on schedule. If a project is delayed, nd the business explanation

for the delay. An FP&A professional in a small food and beverage “best-performing” company

in China mentioned how strong FP&A “provides sound support for business decisions, timely

measuring of output making it easy to adjust, and the ability to estimate project impact before it

is carried out.”

Principle 4: Quickly identify the business reasons behind plan-to-actual nancial variances.

While variances are often seen as something to avoid, they can be extraordinarily helpful in

understanding what’s happening in the business. Comparisons, however, rarely tell the whole

story. Without a real business plan, all the nancial analyst can say is something like, “We have

a -2% variance in revenue because we did not sell as much as we forecasted.” There’s very little

business insight offered in that statement.

In contrast, the best-performing companies quickly and condently:

• Identify plan-to-actual nancial variances.

• Identify the business reasons for plan-to-actual variances.

For example, suppose there was a real plan to grow revenues by 8%, but a key

marketing campaign launch date was delayed and a promotional event did not draw the

response rate anticipated. Best-performing companies delve much deeper into those issues.

What caused the delay in the marketing campaign? If it was an advertising agency issue, maybe

the company needs a new one? If the root cause was that the marketing person leading the

campaign left the company on short notice, perhaps there is a succession planning issue. The

analysis can reveal real business issues and facilitate continuous improvement in the enterprise.

One respondent commented, “Diving deep into the numbers gives you a detailed picture of

the company. Mostly FP&A helps me understand where we currently stand. The environment is

highly dynamic, however, so your plans are dated soon after accomplished.”

Again, the frequency of variance analysis depends on the degree of controllability and

variability of the results. Investing in systems that support this type of analysis will provide many

benets, even for smaller rms.

Principle 5: Make course adjustments when falling behind on nancial or operational goals.

Rather than just adjusting their expectations downward, the best-performing rms are agile.

They are not just focused on nancial progress but also on the progress being made on

10

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

operational goals as well. They are proactive about getting back on track. On the other hand,

FP&A reporting at the worst-performing rms is often just nancial reports showing variances.

A respondent from a worst-performing company said, “FP&A needs to disseminate not only

accurate information but ‘actionable’ information—meaning, not only provide quantitative data

but qualitative as well. Moreover, the reports are based on historical data with no qualitative or

quantitative information besides the ‘slap on the wrist’ if you are going over your budget. They

do not understand there is a difference between being proactive vs. reactive.”

An agile company does more than just forecasting. Planning for success is what drives

value; merely forecasting success does not. Of course, forecasting is still a vital function that

serves as an early warning system and should provide an unbiased projection. Gaps between

the forecast and the plan should prompt a dialogue regarding the underlying business issues

causing the gaps.

Keep in mind that forecasts should not focus exclusively on the nancials. The progress

of the initiatives and project plans should also be assessed. This type of analysis requires

an understanding of the business and the initiatives, which goes above and beyond the

understanding of nancial models and may require additional training and development for

FP&A staff.

Accountability Principles – Building a Culture of Accountability

The next three principles are designed to help foster a culture of accountability. As good as any

plan is, it takes people to implement it. People do care if the organization achieves its goals, but

they care even more about achieving targets they own, especially if there is economic incentive

to do so. In this section, we discuss how to foster a culture of accountability.

Principle 6: Cascade both nancial and nonnancial operational targets down the

organization to more specic targets.

The best-performing organizations integrate nancial and operational planning. This extends to

the cascading of goals down through the organization. Higher-level goals (such as growing sales

by 1,000 units) are broken down into incrementally smaller goals and potentially further broken

down to an individual level (so the 1,000-unit sales growth cascades down into regions, districts,

and salespeople). Cascading of goals is a critical element of building accountability. While some

companies cascade nancial targets, the best-performing organizations cascade operational

targets as well.

The study found that public companies are more likely to cascade nancial goals from

high to low organizational levels than privately held companies or nonprots. One reason could

be that public rms have an especially high need to reach nancial goals for stockholders and

analysts. On the other hand, they are not more likely to cascade operational targets than private

companies or nonprots.

11

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Principle 7: Hold people accountable for delivering nancial results and link to nancial

incentives.

The best-performing organizations translate strategy into actionable initiatives and then further

rene specic projects. They hold people accountable for delivering nancial targets but go

a step further by linking those results to nancial incentives. So “being accountable” in these

organizations takes on deeper and more personal meaning than simply being called out for

failing to deliver on a commitment. More specically, the best-performing companies:

• Clearly identify those people who are responsible for delivering the nancial targets in

the annual plan or budget.

• Hold these people clearly accountable for delivering on those nancial targets.

• Provide those same people with nancial incentives that are tied to achieving their

nancial targets.

One issue to address is how to handle events that affect nancial performance but

are out of the control of those accountable for meeting the targets. To remedy this, make

controllability a key consideration for performance appraisals and nancial incentives. For

example, do not hold the sales director responsible for returns based on quality failures. Another

example is not to over-allocate executive overhead to departments for performance evaluations.

It is important to select appropriate performance measures. In general, good individual

performance measures should:

• Align employees’ goals with that of the organization’s key success drivers.

• Yield relevant information about the actions or decisions of the employee (i.e., high

controllability and low interdependency).

• Be easy to understand, measure, and communicate.

• Be available on a timely basis.

Keep in mind there are no perfect performance measures. There are always trade-offs.

Ideally, it is optimal to tie incentives to goals that are specic, measurable, actionable, relevant,

and time-bound (SMART).

Further, “accountability” should mean responsibility for leading the way to reaching

nancial targets. Those given this responsibility should be in the best position to enable the

organization to reach the goals and, if they are not achieved, be most knowledgeable about

what happened and why. Companies that use accountability to blame and penalize those who

do not achieve their nancial goals are creating an environment of distrust and responsibility-

shirking, and encouraging nger-pointing. It is critical that incentives avoid “gamesmanship,” or

motivating managers to optimize their own performance at the expense of the organization. Best

performers foster a culture where those accountable feel free to report what really happened so

the organization can learn from the experience and reach its goals in the future.

Generally, incentives should be based on both nancial and nonnancial targets and

include both individual and company-wide metrics. Also, targets could be adjusted to the

relative performance of other companies in the industry.

12

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Principle 8: Hold people accountable for delivering operational results and link to

nancial incentives.

This principle goes back to the theme of operational and nancial plans being tightly integrated

in the best-performing organizations. Accountability is not just about hitting the nancial targets,

it is also about achieving the operational targets that ultimately drive the nancials. Because

operational changes drive nancial performance, the best-performing organizations:

• Identify people who are responsible for delivering specic operational targets

(for example, give the head of manufacturing responsibility for delivering a 5%

productivity improvement goal).

• Hold them accountable for delivering the operational targets (for example, assign

milestone delivery dates to key members of a project team to review progress on

their goals).

• Provide them with nancial incentives tied to achieving their operational targets

(such as meeting operational targets is included in the bonus calculations).

Companies can use a strategy map to ensure operational goals are clearly linked to

nancial outcomes in a cause-and-effect linkage. Metrics should include both leading and

lagging indicators of performance that ultimately lead to desired nancial outcomes.

Advanced Principles – Taking FP&A to the Next Level

The last four principles focus on business drivers and integrating them into FP&A. An

organization’s strategy should focus on moving the key drivers in the right direction. To do that,

an organization must have a rm understanding of what drives success in the business, dene

measures for those drivers, and establish targets for them. At that point, strategy becomes

“practical” in the sense that it is focused on those things that will drive its success.

Principle 9: Identify what drives business success and develop key performance indicators

(KPIs) for those drivers.

The best-performing organizations codify or formalize what drives success in their business with

associated measures so they become widely shared and understood. More specically, these

companies:

• Identify what drives success in their business.

• Develop clear measures for those drivers.

For example, in the high-tech industry, innovation is considered a driver of success. The

best-performing organizations take that driver and develop a clear measure for it, such as the

percentage of sales coming from products introduced in the past two years. These measures are

often referred to as key performance indicators (KPIs). KPIs should be tracked not for the sole

purpose of having something to put on a dashboard or scorecard, but because they have been

determined to drive success. The best-performing organizations also have specic actionable

plans for achieving success on those KPIs.

13

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Each industry has unique KPIs that drive success in that industry. For example, in the

hotel industry, customer loyalty, occupancy, and achievable room rates are frequently cited as

drivers of success. The question then becomes how to measure those drivers. Customer loyalty

can be measured by an index used to assess to what extent a customer would recommend that

hotel. Combining the occupancy rate and average room rate determines revenue per available

room, another common way to assess the hotel’s success.

Principle 10: Establish long-term and short-term targets for the KPIs.

As discussed in the previous section, the best-run organizations do a better job of identifying

and measuring what drives their success. Instead of loosely conguring aspects of FP&A, the

best-performing organizations tightly integrate them. To leverage their KPIs, these companies:

• Establish long-term targets for KPIs.

• Establish short-term (usually annual) targets for those measures.

In doing so, they develop a path between where they are now and where they want to

be. Further, they put those drivers to work by establishing both long-term and short-term targets

for those drivers. They have a vision of where they want to be on those measures in the long

term but also “make it real” by establishing short-term targets.

Principle 11: Develop initiatives and operational projects to achieve KPI targets.

Once best-performing organizations have dened their drivers and set targets, they:

• Establish strategic initiatives to achieve the long-term targets.

• Identify operational projects and plans to achieve the short-term targets.

This underscores the theme that the likelihood of achieving a goal increases with clear

plans, rather than simply wishful thinking. It is critical to both develop strategic initiatives to

achieve organizations’ long-term targets and establish actionable operational tactics to achieve

related shorter-term targets.

Principle 12: Monitor results of KPIs and link to nancial incentives.

Lastly, to help build accountability, organizations should:

• Monitor results of KPIs for progress toward their documented goals.

• Tie incentives to achieving the goals.

To avoid gaming the system and motivating managers to optimize their own

performance at the expense of the organization, incentives should be based on both nancial

and nonnancial targets and include both individual and company-wide metrics. Unfortunately,

compared to the other principles, relatively fewer organizations tie incentives to achieving goals.

Again, it is optimal to tie incentives to SMART goals.

14

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Support for the 12 Principles

Appendix 1 provides demographics and results of the study and shows support for the value of

the 12 principles. We found the best-performing companies are much more likely to be following

the principles and related practices compared to middle- and worst-performing groups. The best

performers are following more of the specic practices on average than the other groups: best

(9.1), middle (7.4), and worst (5.1). The practices that most distinguished the best performers

from the rest are:

• Variances: quickly and condently identify plan-to-actual nancial variances

(Principle 4).

• Responsibility: clearly identify people who are responsible for delivering nancial

targets in our annual plan (Principle 7).

• Accountability: hold these people clearly accountable for delivering the nancial

targets (Principle 7).

• Operational: provide nancial incentives to those who have responsibility for

delivering operational targets (Principle 8).

• Targets: establish long-term targets for KPIs (Principle 10).

• Initiatives: develop strategic initiatives to achieve the KPI long-term targets

(Principle 11).

The People Side of FP&A

People manage the FP&A process, and, in many respects, the process is only as good as the

people managing it. Key FP&A skills and capabilities include:

• Understanding the underlying business.

• Building effective working relationships outside of nance and accounting.

• Understanding the specic area or department they are supporting.

• Communication skills.

• Technical skills (for example, accounting, working with spreadsheets, and so on).

Understanding the Underlying Business

If FP&A staff are to become trusted advisors and partners in the business, they need to have a

rm understanding of the underlying business. They need to know how the business is run, the

major inuences or levers of the business, who the customers are and how they buy, and the

strengths and weaknesses of competitors. For example, one of the authors was hired as a new

cost analyst at a factory making expensive food-processing equipment. One of his assignments

was to track the costs of each project and estimate the nal protability. Although each project

was specically designed by engineers, there were always parts of the manufacturing process

that could take more (or less) time than planned or parts of the product that were more (or less)

expensive than planned. It was imperative that he understand the manufacturing process and

employees to know what questions to ask.

15

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Crucial to the business-partner role of FP&A employees is a solid knowledge of the

business and its operations. This is how they can earn trust and build credibility. That trust and

credibility are shattered when employees are perceived as having only supercial knowledge

and, conversely, built up when they demonstrate in ways small and large that they are students

of the business.

As we have seen in the 12 principles outlined in this report, the best-performing

organizations fuse together the operations and the nancials of the business. That means it is not

enough for FP&A employees to understand the nancial side; they need to know the operational

side as well if they are ever going to be able to connect the two. A respondent from a worst-

performing company lamented, “FP&A needs to better understand the underlying business;

moreover, they need to understand the cost drivers of the development process and try to come

up with solutions instead of delivering problems.”

Building Effective Working Relationships Outside of Finance and Accounting

To successfully build working relationships, it is essential to establish credibility. The people

on the front lines know better than anyone else what is going on in the business, and it is the

FP&A professionals’ job to learn and communicate that. They will be able to offer a real business

explanation and insight if they have built good working relationships and are connected to and

aware of what is going on around the company.

It is not enough to know that prot came in less than expected because cost of goods

sold was higher than planned. That is an accounting answer. Instead, discussions with the

production manager might reveal the company faced a stock-out of a key material that had to

be air-shipped at considerable cost to meet customer demand. Further business analysis may

reveal that the demand forecast was off. To help safeguard that this does not happen again, the

analyst might meet with the sales manager and determine this is another reason to implement

the new sales and operational planning process proposed the previous month and currently

under review. All of these ndings are more probable through good working relationships with

those outside of the nance department.

Understanding the Specic Area or Department They Are Supporting

Besides understanding the business, FP&A professionals also should understand the issues

and language of the departments they support. For instance, the challenges of the logistics

department are quite different than those of marketing or human resources. Each functional area

needs FP&A professionals to understand its unique challenges and how it runs its side of the

business.

Many of the more successful FP&A professionals will take practical steps to get to know

the department they serve, such as attending weekly staff meetings or facilitating monthly

reviews of plan vs. actual results. That way when the plan (or forecast) cycle starts up again, they

are already part of the team.

16

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Communication Skills

FP&A professionals need to be able to communicate effectively with the rest of the organization.

Consider the monthly management reporting package that provides variance analyses to help

executives understand what happened in the business and why. Ask yourself: How clear are the

variance explanations? Could anyone in the organization read it and understand what is being

communicated? Consider all the exhibits, reports, and templates used in the annual plan or

monthly forecast. Do people outside of the nance department understand them and what they

are used for? Are there actual business decisions being made based on these reports? If not, is

that an indication of their lack of utility? To nd out, ask the report recipients.

Verbal communication also happens while gathering facts. For example, to nd an

explanation for a nancial variance, asking the right questions in the right way and avoiding

ambiguity and forcing clarity can make all the difference in getting the best explanation.

Likewise, using verbal skills to clarify an information request can avoid a lot of misunderstanding

and rework. FP&A employees should take responsibility for communication and ensure all sides

understand what is being asked and why.

FP&A staff members often make presentations during the planning process, as well as

during monthly reviews, comparing actual results to the forecasts for the period. How those

presenters express this information can either help executives grasp the issues quickly or leave

them confused. One common complaint is that an FP&A staff member will display a chart

crowded with data in small font and begin by saying “As you can clearly see…” The presenter

has not adequately provided context for what is on the slide nor explained what is on it. They

have jumped right in, assuming the audience knows much more about what they are looking at

than they actually do.

Technical Skills

The number of technical skills that all management accounting professionals are expected to

have keeps increasing. Excel, nancial modeling, forecasting and budgeting, variance analysis,

cost and protability management, data analytics, return on investment (ROI) and net present

value (NPV) development and analyses, accounting, and reporting are just the start. Other

emerging technology skills include process automation, articial intelligence (AI), business

analytics, data security and storage, and data visualization.

Another emerging technical skill is project planning. This includes knowing how to

develop a project charter (dening the goals, scope, approach, team structure, and so on) and a

project plan (like a Gantt chart) with activities, tasks, resource estimates, milestones, and dates.

A respondent from a best-performing company said, “Effective FP&A can ensure coordination

of initiatives, projects, and programs.” While FP&A professionals might not be leading the

project, they may be tasked with managing it from a reporting and control perspective. Project

management skills include being able to update the project plan as necessary, manage the

progress reporting process, and facilitate meetings.

17

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Beyond traditional nancial modeling, the ability to develop a business case is another

skill that is increasingly required. A business case includes how the investment would advance

the strategy of the organization, the resource requirements, the estimated implementation

timeline, alternatives considered and why the team chose a certain path, and how to package

and present the plan.

Key Competencies

In the study, we compared the best-performing organizations against the worst-performing in six

key FP&A skill areas. We found the following key competencies that most distinguished those in

the best-performing group from the other groups (in order):

• Building effective working relationships outside of nance/accounting.

• Understanding the specic area/department they are supporting.

• Written communication.

• Verbal communication.

A study participant from a large best-performing nancial services company in the U.K.

described their people with these competencies: “The business partners in our organization

are the key to everything—they know how to complete the annual planning requirements for

marketing, they can get letters of intent through for mergers and acquisitions, they understand

the systems and processes and people necessary for human resources, they do the revenue

walks (modeling) to calculate growth, etc.”

For more on specic key competencies of FP&A professionals, see the “Strategy,

Planning & Performance” domain section in IMA’s Management Accounting Competency

Framework.

Selling the Value of Improved FP&A Practices to Top Management

Convincing top management of the value of improving FP&A can be more difcult than

expected. It is difcult to measure the benets of most administrative initiatives, such as

improving the FP&A process. Most leaders consider the benets of “intangibles” to be too

difcult—if not impossible—to measure, so they do not measure them, which leads to little to

no improvement in the FP&A process. Like other more tangible operational improvements, they

want to see the ROI rst.

So how do we measure the expected value for investing in FP&A? If we dene

measurement as “a quantitatively expressed reduction of uncertainty based on one or more

observations,” virtually anything can be measured.

7

By dening specically what an improvement

in FP&A would look like, we can estimate the operational and even nancial benets. Here are

four steps to do so.

7

Much of this section is based on two sources: (1) Douglas W. Hubbard’s book How to Measure Anything: Finding the

Value of ‘Intangibles’ in Business and (2) “Measuring the ROI on FP&A,” a presentation given by Gavin Black, Bill Sayer, and

Amber Bowden, at the Association for Financial Professionals (AFP) Annual Conference, October 27, 2013, Las Vegas, Nev.

18

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Step 1. Decide to measure the benets of better FP&A.

There are several potential direct and indirect benets of improved FP&A. Direct benets,

in which something should noticeably improve, include (1) identifying improvement projects,

(2) determining if planned improvements were accomplished, (3) identifying process strengths

and weaknesses, and (4) establishing priorities for future investment. Indirect benets can include

increasing communication between the FP&A team and the rest of the organization, better

understanding of the potential value of the FP&A function, and more effective FP&A outputs.

To measure the benets of better FP&A, identify likely benets, who will benet, and

from whom you need buy-in. In other words, make a case for the improvement with supporting

evidence. You will need to estimate the cost in people’s time and money, as well as what current

practices could be reduced. Be aware from the start of expected challenges and how to address

them. Common challenges include lack of support and resources, time constraints, measuring

the value of “intangible” benets, and dening the scope of the measurement. If all this sounds

doable, proceed to the next step.

Step 2. Dene the measures and collect data.

Dening the measures means agreeing on what improved FP&A would look like and how it can

be observed (for example, improved speed, cost, quality, satisfaction, motivation, inuence, and

engagement). A good place to start is talking with all the key players and asking them to identify

ways that better FP&A could help optimize the decision-making process. Talk about current and

past management decisions and how the various FP&A principles discussed in this SMA could

make a difference.

In his book, How to Measure Anything, Douglas W. Hubbard recommends that before

we decide how to measure something, we rst must clarify the measurement problem by asking

the following questions.

8

a. What is the decision this measurement is supposed to support?

Before deciding what to measure, the rst step should be to identify the problem and decision

for which you intend to use the measurement. For example, if you want to measure employee

engagement, rst decide why you want to measure it. Is the purpose to help improve quality

of work or change hiring and development practices? Or if you want to measure the value of a

proposed FP&A improvement initiative, is the purpose to decide whether to implement a new

FP&A system or to improve the staff’s data analytics skills?

b. What specically would the thing being measured look like as it relates to the decision

being asked?

The key to measuring something that seems hard (or impossible) to measure is to ask what

it would look like specically. For example, if your decision purpose is to measure employee

engagement to help decide whether to improve hiring and development practices, what would

be observable signs of improved employee engagement? Potential answers could be less

8

Hubbard, 2014.

19

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

absenteeism, more ideas generated, fewer defects, or other specic observable actions relating

to engagement and strategic or operational goals.

If the purpose is to measure the value of a proposed FP&A improvement initiative to

improve the staff’s data analytics skills, potential measures might be the before and after impact

levels of FP&A reports, process improvements identied, forecast accuracy, and new business

opportunities identied.

Unfortunately, the contributions of the FP&A team are often not readily apparent. They

are more commonly noticed when there is a mistake or lack of information rather than when they

are helpful and accurate. But to measure the impact of a potential FP&A improvement initiative,

we need to be specic about what we would be looking for. What does improved FP&A look

like? Here are some examples of observable items.

Accurate and timely nancial reporting:

• Impact of FP&A reports for the monthly executive business review meeting.

• Timely internal and corporate parent close.

• Effective compensation support.

Process improvement analysis:

• New ways to improve efciencies and cost savings.

• Identifying waste, fraud, and abuse.

• Terminating expired or ineffective contracts and expenses.

• More or better metric reporting.

Business support and analysis:

• New business development opportunities identied.

• Improved forecast accuracy.

• Better cash management to achieve net positive interest cash ows.

Once you agree on what better FP&A would look like and how to observe it, you next

need to identify how to collect the data. Potential sources of data include the various information

systems, human resources, interviews, minutes of meetings, focus groups, surveys, and so forth.

It may also take a different mind-set among the key players. Unfortunately, not every measure

has readily available data such as units produced. But if you have dened what you are looking

for, then observing that thing becomes a measure. For example, how often have we observed

the FP&A team identifying new business development opportunities? To measure the impact

of FP&A reports for the monthly executive business review meeting, the observation may be

answering the question, “Are we using FP&A analysis more in our strategic decisions?” Or “Are

more/deeper questions being directed toward the FP&A team?”

c. What is the value of additional information?

Information adds value to the extent that it reduces uncertainties in decision making. Knowing

the value of the information helps us to not only identify what to measure but how to measure it.

Sometimes just a few observations can reduce the level of uncertainty signicantly, and collecting

20

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

additional observations may have diminishing benets. There is also the cost-benet side of

collecting additional measurement information. If the decision outcome relates to deciding

whether to invest in an opportunity that could net $1 million per year, it would probably make

sense to spend $10,000 to collect the additional information to help reduce the potential risk of

making a poor decision. On the other hand, if the potential outcome is $10,000, then it would

probably not make sense and a simpler way should be found to reduce the risk of a poor decision.

Step 3. Calculate the net value of improved FP&A.

Calculating the value of intangibles like the potential value of an FP&A investment is easier said

than done. An important contributor in this area was Enrico Fermi.

9

The Fermi method means

to decompose the measurements into specic questions leading to a quantitative decision

model. We break up the estimated costs/benets into things we can observe, such as “Is it more

than X?” The monetary values for each benet or cost by year can themselves be decomposed

further into more variables.

Applying the Fermi method to calculate the value of improved FP&A analysis, such

as an efciency improvement, could be done by multiplying the number of people working

in the improved process, the cost of each person per year, the percentage of time spent on

some unproductive activity, and the percentage of that unproductive time that was eliminated.

Appendix 2 provides an example of estimating the net value and ROI for an FP&A improvement

initiative. Remember that the rst year for most initiatives includes up-front investments that

lower the net value for the rst year. Thus, the analysis should extend beyond the rst year

depending on the time frame of the expected benets. To get the needed buy-in from the key

players on the estimated benets and costs, the analysis should be logical and the estimated

benets should clearly exceed the expected costs.

Step 4. Rene and evaluate the measurement process.

Estimating the costs and benets of FP&A improvement initiatives can improve over time

through periodic reviews, satisfaction with the process, post-project audits, and continued

working together with other departments and upper management to rene the estimation

process. Estimating skills can be improved through calibration techniques.

10

If estimates of

benets are shown to be reliable over time, top management is more likely to sign off on future

improvement initiatives.

9

Fermi (1901-1954) was a physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1938 for his work on nuclear energy.

He was also a master estimator with a knack for nding intuitive ways of measuring things that seemed too

complex to measure.

10

Hubbard, 2014.

21

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

The Role of Technology in FP&A

FP&A is a decision-making platform, and technology needs to enable this platform. It should

meet reporting and business intelligence needs, as well as planning and budgeting, in an

integrated system. One respondent in a best-performing company said, “Due to the real-time,

interconnectivity of our systems, we know exactly where we are at all times.” In the study, we

found the best-performing organizations are slightly more likely to use dedicated FP&A tools

than the worst-performing organizations. And those rms primarily using an FP&A application

are signicantly more likely to identify plan-to-actual nancial variances and the reasons for them

than those rms primarily using Excel. The rationale behind this could be that the FP&A process

on the whole is more rigorous and operationally focused in the best-performing organizations.

Technology that enables the process would help free up FP&A professionals to focus on those

value-added activities.

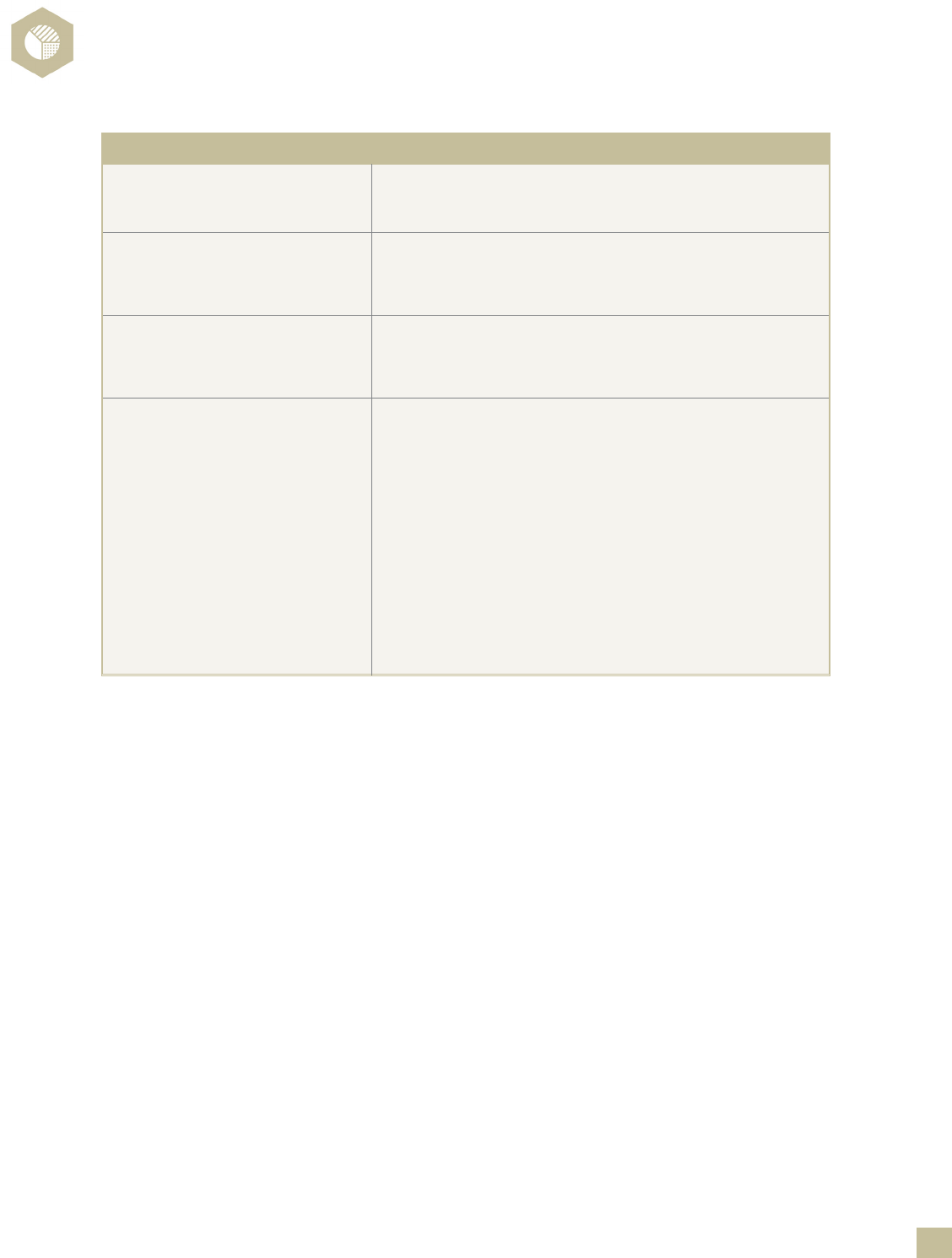

Table 2 provides some guidelines to help identify technology enablers required to

support the 12 principles.

1. System should integrate with or natively include project management software (such as MS Project).

2. System should accommodate both long-term and short-term planning.

3. System should support the use of nonnancial or statistical/operational data.

4. System should support the use of narratives to capture the business reasons behind key variances.

5. The system should support scenario planning and what-if analysis to model key potential changes

in the business.

6. The system should support predictive analytics to anticipate key changes.

7. The system should make it easy to “zip or unzip” goals at any level.

8. The system should capture both nancial and operational goals.

9. The system should integrate with human resources and performance management systems to capture individual

goals, track achievement, and calculate rewards.

10. The system should integrate with or provide dashboard capabilities.

Table 2: Guidelines to Help Identify FP&A Technology Enablers

22

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Where to Start

The easiest place to start is with an assessment of the current state of FP&A in your organization.

Appendix 3 provides the same survey questions used in our study of FP&A practices. It will not

only help you assess your company’s FP&A practices, it will also provide guidance for making

improvements to the process. For comparison, Figure A2 reports the specic practices within the

12 principles that most differentiated the best performers from the rest in the study.

In addition to the assessment, below are some specic action items to consider for

getting started:

• Redesign the planning calendar to better synchronize strategic planning with the

annual operating plan.

• Facilitate a workshop for executives to document “what drives success in this

business” and follow up with proposed measures for those drivers.

• Take preliminary steps to document the linkages between those drivers and the

business’s nancial model.

• Establish annual operating plan objectives by identifying outcomes and timing.

• For the rst year, “start small.” Incorporate just two or three signicant projects

into your annual operating plan/budget and use these to build up experience and

condence in linking operations to nancial outcomes and tracking the project

progress.

• Establish a real follow-up mechanism (at least quarterly, if not monthly) to evaluate

progress answering the question, “Are we doing and achieving what we set out

to do?”

• Work with the human resources department to understand the current variable

compensation structure and open up a dialog regarding incorporating relevant

principles.

• Download the IMA Management Accounting Competency Framework and use it as a

starting point to understand what a competency model is and how to apply it to your

FP&A organization.

• Institute a rotation program to bring operational people into FP&A (and vice versa).

• Train staff in basic project management (for example, how to develop a project plan

with activities, tasks, and milestones).

• Provide training for nance staff with FP&A responsibility in building effective working

relationships with those outside the nance department.

• Develop or join an FP&A principles roundtable group to share and learn from others’

experience.

23

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Conclusions

The question “Does FP&A add value?” is a little like asking “Does marketing add value?”

Marketing itself is neither useful nor a waste of time: It is how well marketing is done and how

effective it is that matters. Likewise, the value FP&A delivers to an organization depends on how

well it is performed.

In this SMA, we have discussed 12 principles of effective FP&A supported in a related

study. The best-performing organizations tend to take a much more rigorous approach to FP&A:

• They integrate all the components of FP&A.

• They merge operational and nancial planning and have a deep understanding of

how operational metrics drive their nancial results.

• They track progress of initiatives designed to move the operational numbers in the

right direction just as closely as they monitor nancial results.

• They hold people accountable for delivering results and link pay with performance.

• They translate strategy into action and make sure initiatives are properly resourced

and accounted for in the budget.

• They tie incentives to SMART goals.

• They make course adjustments when they identify the need to get back on track.

If nothing else, FP&A professionals can benet greatly by honing their relationship skills.

Building effective working relationships outside of the nance department—and understanding

the underlying business and the departments they are supporting—will go a long way in

becoming business partners. Further, the burden is on FP&A staff to learn how to communicate

effectively with the rest of the organization. Without it, decision makers will go elsewhere to

get the information and analysis they need. Ask those outside the nance department if they

understand the purpose of the exhibits, reports, and templates used in the annual plan. If so, do

they use them in managing the business? If not, nd out why.

FP&A has the potential to provide valuable decision support for the many decisions

made during the planning process and as the strategic plan is executed. But it takes investing

time to get to know the specic areas it supports, develop relationships, and build trust and

rapport to provide business analysis specic enough to make a difference.

24

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Appendix 1: Survey Demographics and Results

How We Conducted the Study

In April 2017, IMA

®

(Institute of Management Accountants) sent survey invitations to more than

25,000 global nancial executives and managers with experience in their company’s FP&A

practices. We received 839 responses, a 3.3% response rate. We eliminated 139 incomplete

responses, leaving 700 usable responses from a wide variety of industries. Both large and small

companies were represented, with 20% having more than $1 billion in revenue, 26% between

$100 million and $1 billion in revenue, and 54% below $100 million in revenue. Almost half had

more than 500 employees and 19% had more than 5,000.

Survey Demographics

The survey covered both for-prot companies (87.6%) and not-for-prot institutions (12.4%). The

majority of the not-for-prot institutions were colleges and universities (42%), 501(c)(3) (20%),

and nongovernmental organizations (13%). Roughly two-thirds of respondents were in nance/

accounting/FP&A, with the rest from other areas including executive management (9%) and

manufacturing/operations (7%).

In terms of industries, manufacturing was well represented, as was retail, nancial

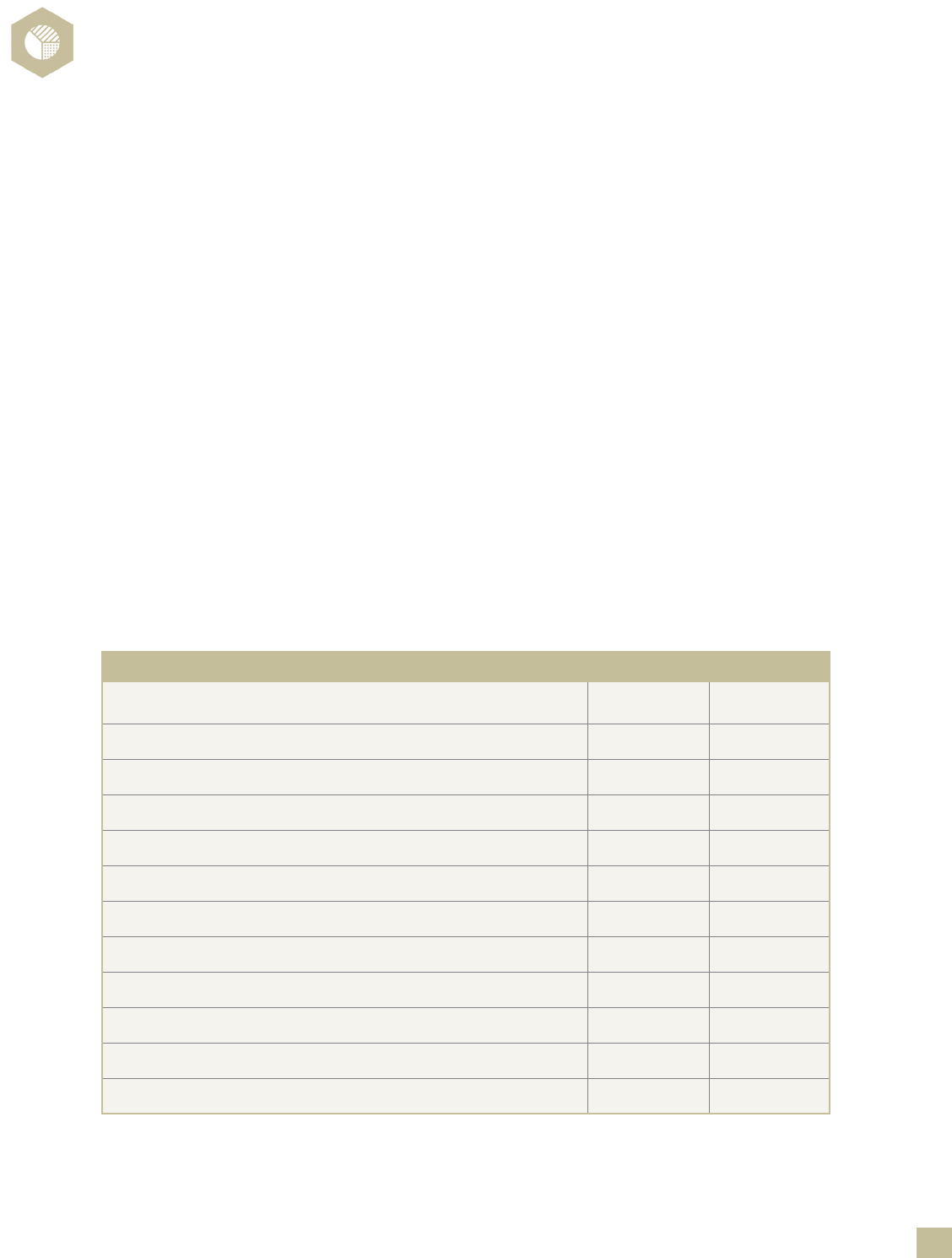

services, and technology (see Table A1).

No. Percent

Manufacturing: Aerospace, Automotive, all other Manufacturing 110 16%

Retail: Apparel, Consumer Packaged Goods (CPG), Wholesale/Retail 41 6%

Financial Services: Banking, Insurance, Brokerage, Investment 67 10%

Technology: Biotech, Computer, Software, Technology, Telecom 72 10%

Construction and Real Estate 41 6%

Utilities and Transportation 68 10%

Business Services: Advertising, Consulting, Legal, Publishing 51 7%

Healthcare: Facilities, Payers, Providers, Supporting Products, and Services 48 7%

Other 116 17%

No response 86 12%

Total 700 100%

Table A1: Industries

25

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

Survey Results

We dened the best-performing enterprises as those that reported they (1) consistently meet

or exceed the targets they set for themselves as a company/institution, and (2) consistently

meet or exceed the results of their competitors. Of the 700 usable responses, 367 were from

organizations that met the criteria for “best performers.” We dened the worst-performing rms

as those organizations that reported just the opposite. They both (1) consistently fail to meet or

exceed the targets they set for themselves as a company/institution, and (2) consistently fail to

meet or exceed the results of their competitors. There were 138 organizations that fell into the

“worst performers” category. The remaining 195 were categorized as “middle performers.”

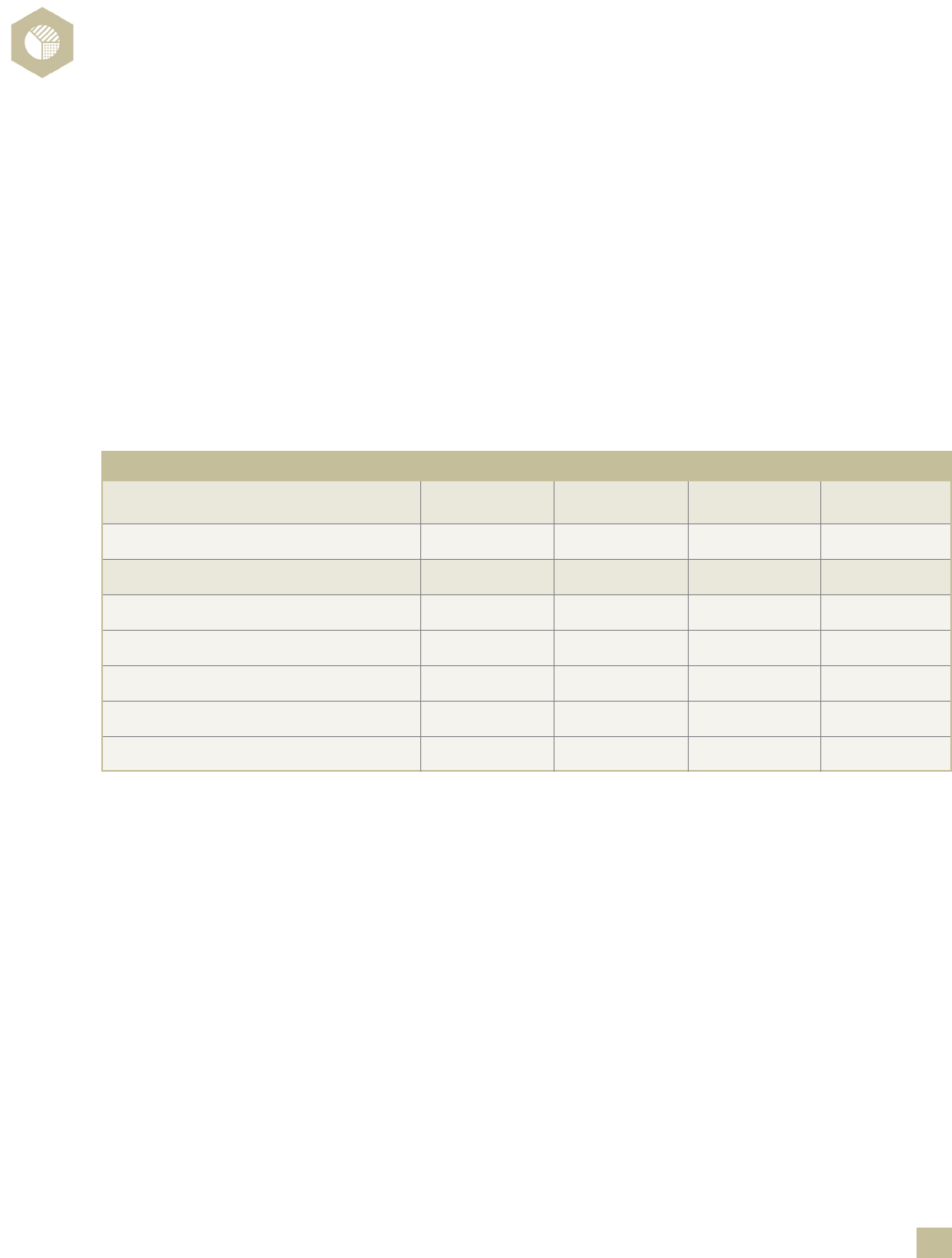

Table A2 shows that best performers overall outpace the other groups on revenue

growth rates, protability, and market share.

Medium- to large-sized companies were more likely to recognize the value of FP&A.

Further, those companies primarily using FP&A software rather than spreadsheets were also

more likely to recognize this value of FP&A.

Results of Survey Study on the 12 Principles of Effective FP&A

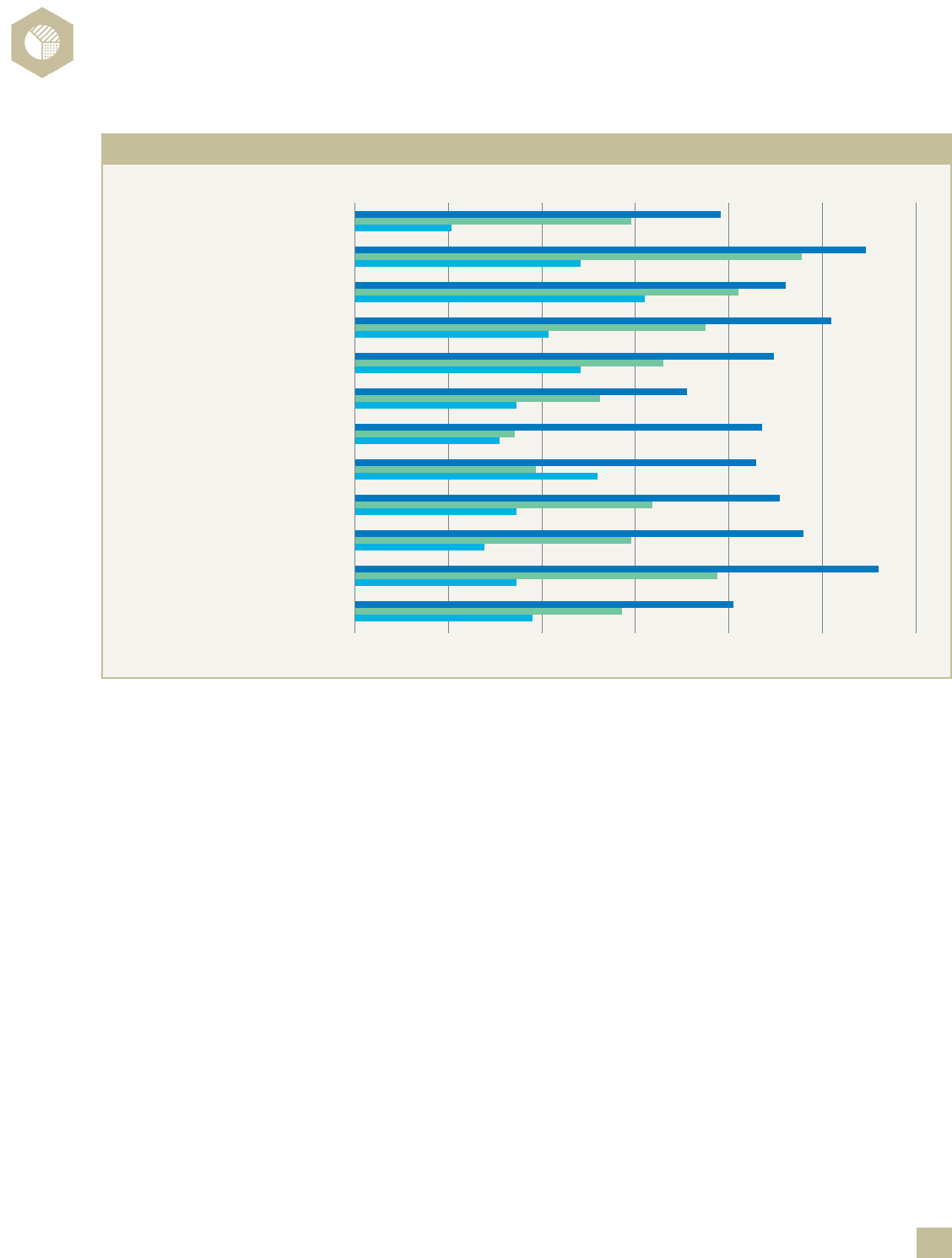

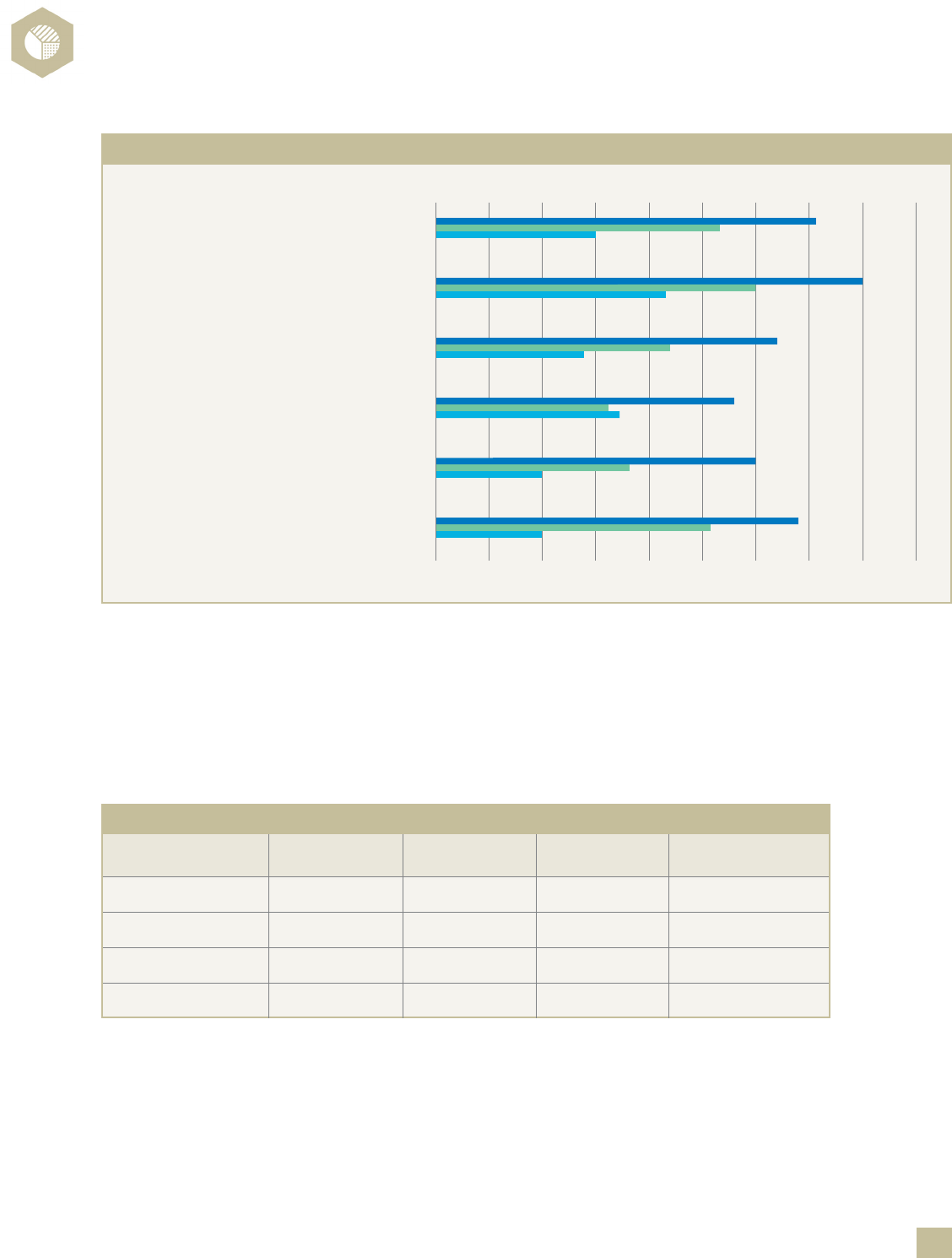

Figure A1 compares the percentage of those who “completely agree” from best, middle, and

worst performers for each specic practice within each of the 12 principles. As shown, the best

performers more often implement each principle. The principles that most distinguish the best

performers from the rest are P2, P4, P7, P8, P9, P10, and P11. Based on Chi Square tests, all

differences between the three performance groups are statistically signicant at p< 5% except

for P3.

Best Performers Middle Performers Worst Performers All Companies

Total number of respondents 367 195 138 700

Over the past ve years

Average revenue growth rate 10.5% 9.5% 7.5% 9.6%

Revenue growing faster than competitors 94.1% 90.1% 71.7% 88.5%

Protability better than competitors 79.0% 56.9% 36.8% 64.3%

Market share better than competitors 72.5% 53.3% 35.9% 59.8%

Realizes the full potential of FP&A (1-100; mean) 65.6 58.2 46.5 59.7

Table A2: Growth Rates, Protability, and Market Share for Best vs. Worst Performers

26

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

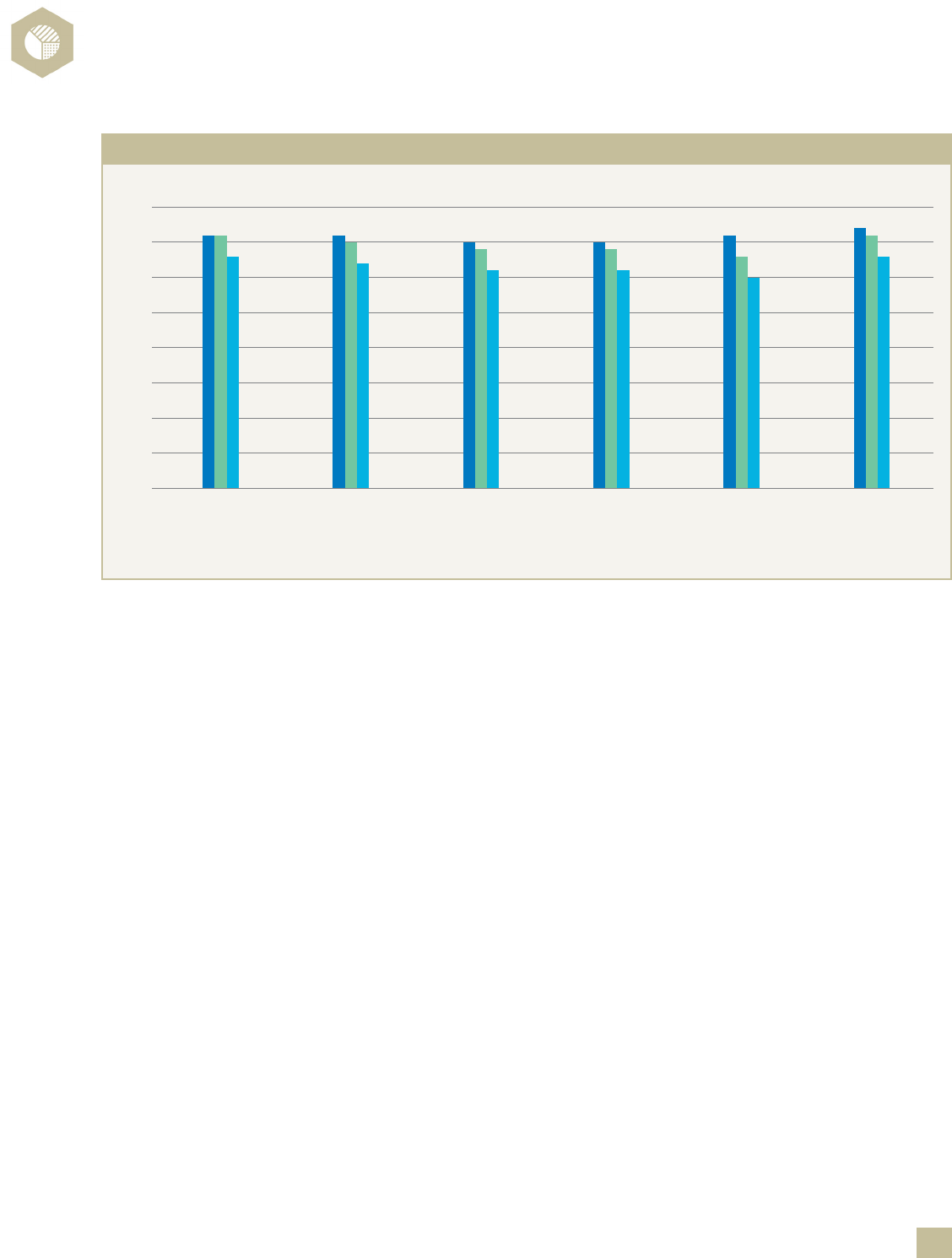

Figure A2 compares the percentage of those who “completely agree” from best,

middle, and worst performers for specic practices within the 12 principles that most

differentiate the best performers from the rest. The key differentiator practices were identied

based on univariate Chi Square tests and multivariate binary logistical regression analysis

comparing best performers against worst performers and best performers against middle

performers for all practices. All differences between best- and worst-performing rms are

statistically signicant at p< 5% in the Chi Square tests.

0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30%

P1: Strat plan with projects

*P2: Budget resources needed

P3: Operational drives nancial

*P4: Identify variances and reasons

P5: Make course adjustments

P6: Cascade targets down

*P7: Accountable for nancial

*P8: Accountable for operational

*P9: Identify success drivers and KPIs

*P10: Long/short-term KPI targets

*P11: Projects to achieve KPI targets

P12: Link KPIs to nancial incentives

Figure A1: Percent Who “Completely Agree” with All Practices within Each Principle

n Best n Middle n Worst

Note: Survey respondents were asked to what degree they agreed or disagreed with each statement: 1=completely disagree;

2=somewhat disagree; 3=somewhat agree; 4=completely agree. Each question for each principle can be found in Appendix 3.

27

PLANNING &

ANALYSIS

Key Principles of Effective Financial

Planning and Analysis

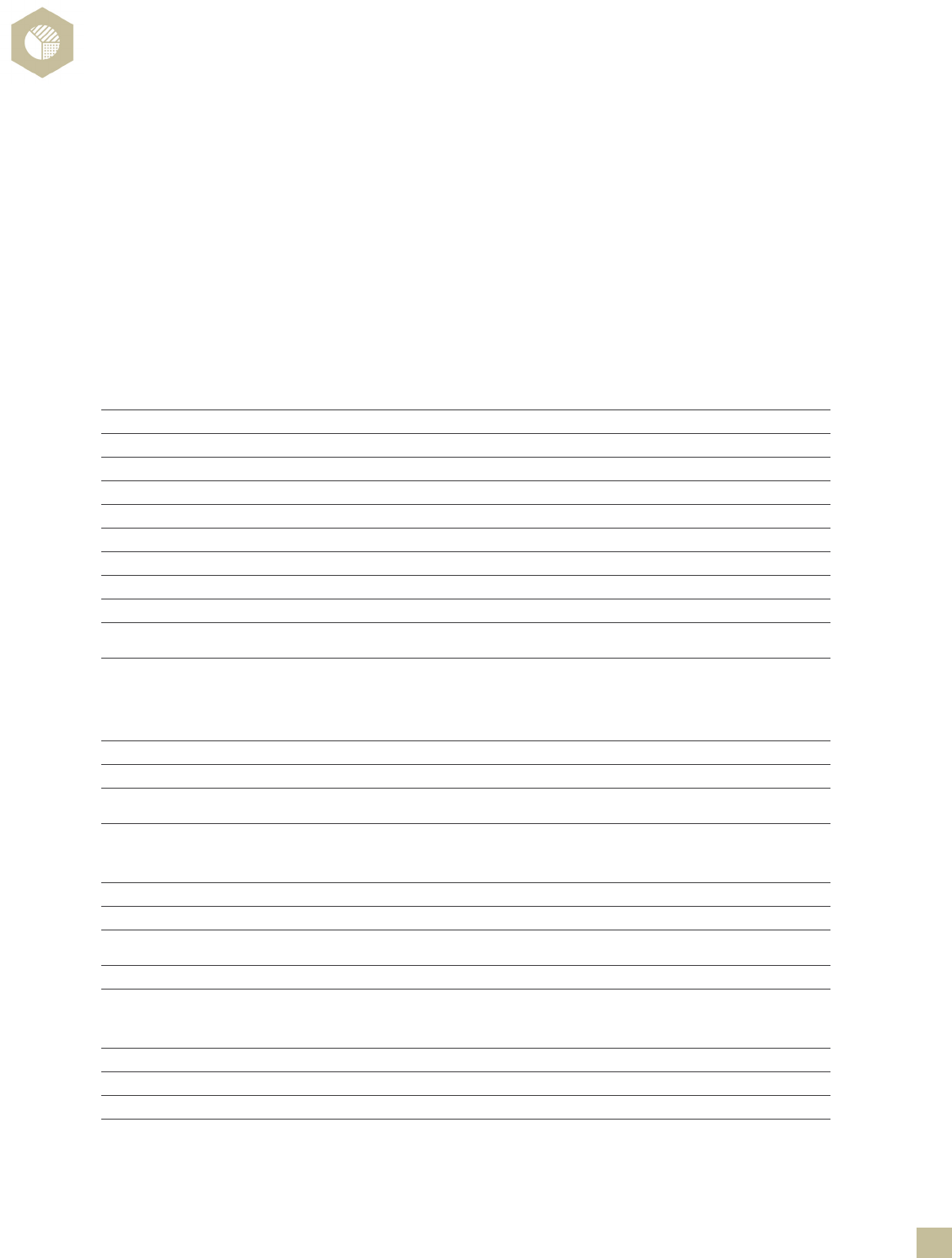

Table A3 compares the number of practices that the respondents from best, middle, and

worst performers answered “completely agree” to when asked if they followed each practice

and suggests the more practices followed, the better the FP&A outcomes. The differences

among the groups are statistically signicant at p< 5% in ANOVA analysis.

0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40% 45%

P4: Quickly and condently identify plan-to-actual

nancial variances

P7: Clearly identify people who are responsible for

delivering nancial targets in our annual plan

P7: Hold these people clearly accountable for

delivering nancial targets

P8: Provide nancial incentives to those who have

responsibility for delivering operational targets

P10: Establish long-term targets for KPIs

P11: Develop strategic initiatives to achieve the

KPI long-term targets

Figure A2: Percent Who “Completely Agree” with Specic FP&A Practices

n Best n Middle n Worst

Note: Survey respondents were asked to what degree they agreed or disagreed with each statement: 1=completely disagree;

2=somewhat disagree; 3=somewhat agree; 4=completely agree. Each question for each principle can be found in Appendix 3.

Performance Group Mean Standard Deviation Median Range

Best performers 9.1 9.83 7 0-29

Middle performers 7.4 8.31 4 0-28

Worst performers 5.1 6.87 7 0-26

All companies 7.8 9.02 4 0-29

Table A3: Number of Practices for Each Performance Group