WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

INEQUALITY

IN A RAPIDLY

CHANGING

WORLD

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS

The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital

interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and

national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates

and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environmental data and information on which

States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of

policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental

bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii)

it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks

developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level

and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities.

NOTE

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in the present publication

do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the

United Nations concerning the legal status of any country or territory or of its authorities, or

concerning the delimitations of its frontiers. The term “country” as used in the text of this

report also refers, as appropriate, to territories or areas. The designations of country groups in

the text and the tables are intended solely for statistical or analytical convenience and do not

necessarily express a judgement about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the

development process. Mention of the names of rms and commercial products does not imply

the endorsement of the United Nations. Symbols of United Nations documents are composed

of capital letters combined with gures.

ST/ESA/372

United Nations publication

Sales No. E.20.IV.1

ISBN 978-92-1-130392-6

eISBN 978-92-1-004367-0

Copyright © United Nations 2020

All rights reserved

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

I

The World Social Report 2020: Inequality in a rapidly changing world comes as we

confront the harsh realities of a deeply unequal global landscape. In North and South

alike, mass protests have ared up, fueled by a combination of economic woes,

growing inequalities and job insecurity. Income disparities and a lack of opportunities

are creating a vicious cycle of inequality, frustration and discontent across generations.

The World Social Report 2020 documents deep divides within and across countries

despite an era of extraordinary economic growth and widespread improvements in

living standards. The report also underscores how gender, along with ethnicity, race,

place of residence and socioeconomic status, continue to shape the chances people

have in life.

In some parts of the world, divides based on identity are becoming more pronounced.

Meanwhile, gaps in newer areas, such as access to online and mobile technologies,

are emerging. Unless progress accelerates, the core promise of the 2030 Agenda

for Sustainable Development – to leave no one behind – will remain a still distant goal

by 2030.

The inequality challenge is global, and intimately connected to other pressing issues of

our times: not only rapid technological change, but also the climate crisis, urbanization

and migration. In many places, the growing tide of inequality could further swell under

the force of these megatrends.

The World Social Report 2020 sends a clear message: the future course of these complex

challenges is not irreversible. Technological change, migration, urbanization and even

the climate crisis can be harnessed for a more equitable and sustainable world, or they

can be left to further divide us.

Governments are key players in creating more equitable societies, protecting the most

vulnerable from the negative effects of these trends and ensuring that their benets

as well as adaption costs are broadly and equitably shared. But, in our increasingly

interconnected world, the decisions of other countries can constrain national

policy-making.

International cooperation is more important than ever.

FOREWORD

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

II

As we enter a Decade of Action to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, the

United Nations system will be at the forefront of the ght against inequality, linking

global principles and policy know-how to local action.

The start of the Decade of Action coincides with the seventy-fth anniversary of the

United Nations. To mark this important occasion, we are opening a global conversation

on building the future we want. In a world of dramatic global changes, I encourage

people to express their views on how enhanced international cooperation can help build

a fair globalization.

The World Social Report 2020 frames the debate on how to curb inequality in these

turbulent times. Together, we must challenge the status quo and take action to tackle

deep-seated as well as emerging inequalities once and for all.

António Guterres

Secretary-General

of the United Nations

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

III

The World Social Report is the agship publication on major social development

issues of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) of the United Nations

Secretariat.

The 2020 report was prepared by a team managed by Wenyan Yang in the Division

for Inclusive Social Development, under the guidance of Elliott Harris and Daniela Bas.

The report’s core team, led by Marta Roig, included Maren Jiménez, Alex Julca, Hiroshi

Kawamura, Martijn Kind, Yern Fai Lee, Jonathan Perry and Julie Pewitt. Valuable inputs

were provided by other colleagues in DESA, including Astra Bonini, Clare Menozzi,

Vinod Mishra and Shantanu Mukherjee. The team is grateful to Eduardo Moreno and

his team at UN-Habitat for their valuable inputs to chapter 4 of the report.

The analysis contained in the report is based in part on background papers

prepared by independent experts Aaron Benavot and Kathleen Newland. The

collection and analysis of household survey data conducted by Bin Lian was

extremely important. Sabina Alkire, Corrine Mitchell and their team at the Oxford

Poverty and Human Development Initiative graciously provided data on the

multidimensional poverty index.

The team is particularly grateful to Francisco Ferreira, Carlos Gradín, Stephane

Hallegatte, Kenneth Iverson, Alfredo Jefferson, Christoph Lakner, Hitoshi Osaka,

Heriberto Tapia, Narasimha Rao, Julie Rozenberg and Brian Walsh for their guidance

and advice during the preparation of the report. The team would also like to thank

Jeni Klugman, Jorge Rodríguez as well as those DESA colleagues who provided

comments to the draft report during the formal review process.

At an early stage, the team also beneted from consultations on new research

on inequality with Robert Andersen, Bea Cantillon, Lucas Chancel, Miles Corak,

Hai-Anh Dang, Vidya Diwakar, Anirudh Krishna, Leslie McCall, Abigail McKnight,

Pippa Norris, Celine Thévenot and Stephen Younger.

The report was skillfully edited by Lois Jensen. Camilo Salomon provided the cover,

publication and graphics design.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

IV

Foreword II

Acknowledgements IV

Explanatory notes XII

Executive summary 2

Introduction 16

1. Inequality: where we stand today 19

Key messages 20

Introduction 21

A. Economic inequality 21

1. Income inequality across countries 22

2. Trends in economic inequality within countries 26

a. Regional trends 26

b. Labour and capital 31

c. The impact of policy 32

B. Inequality of opportunity 34

1. Group-based disadvantage, poverty and income inequality 37

2. Trends in group-based inequality 40

C. The price of inequality 45

1. Slower economic growth and poverty reduction 45

2. Limited upward mobility 46

3. Captured political processes, mistrust of institutions and growing unrest 48

D. Conclusions 52

Annex 1: Measuring economic inequality 53

Annex 2: Group-based disparities in access to electricity and sanitation 56

CONTENTS

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

V

2. The technological revolution: winners and losers 57

Key messages 58

Introduction 59

A. Technology, employment and inequality 60

1. Labour-saving and skill-biased technologies 61

2. Share of labour in national income: impacts of labour-saving technology 63

3. Wage divergence: impacts of skill-biased technology 65

B. Current technological divides and opportunities for inclusion 71

1. Technological divides and unequal access to basic services 71

2. New technologies and nancial inclusion 73

3. New technologies in other sectors 75

C. Policy considerations 78

3. Climate change: exacerbating poverty and inequality 81

Key messages 82

Introduction 83

A. Climate change through an inequality lens 84

1. Channels through which climate change exerts its effects 84

a. Livelihoods 84

b. Health and mortality 85

c. Agricultural production and food prices 86

d. Labour and economic productivity 86

2. Determinants of the uneven impacts of climate change 86

B. Unequal exposure and impacts across countries 88

C. Unequal exposure and impacts within countries 93

1. People living in poverty 93

a. Exposure 93

b. Susceptibility 94

c. Ability to cope and recover 95

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

VI

2. Other vulnerable groups 97

a. Smallholder farmers 97

b. Indigenous peoples 97

c. Rural coastal populations 98

D. Distributional effects of climate action: implications for policy 99

1. The effect of mitigation and adaptation policies on inequality 99

a. Mitigation policies 99

b. Adaptation policies 101

2. Promoting a just transition with equitable outcomes 104

a. A systems perspective 105

b. Climate action and social protection 105

4. Urbanization: expanding opportunities but deeper divides 107

Key messages 108

Introduction 109

A. Spatial inequalities: the rural-urban divide 109

B. An increasingly urban world 114

1. Inequality within cities: economic, spatial and social dimensions 115

2. Slums: home to more than 1 billion people 119

C. Policy implications: shared prosperity or rising inequality? 122

1. Cities that work for everyone 123

2. Coordinating, nancing and monitoring urban policies 125

5. International migration: a force for equality, under the right conditions 127

Key messages 128

Introduction 129

A. International migration and inequality among countries 130

1. Migration as part of the development process 130

2. The potential of migration to reduce inequality among countries 133

a. Migration of highly skilled workers 133

b. Migration of less-skilled workers 135

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

VII

B. International migration and inequality within countries 135

1. The impact of remittances on income distribution 136

2. Migrants and the functioning of labour markets 138

a. In countries of destination 139

b. In countries of origin 140

3. Group-based inequality and the immigrant experience 140

C. Maximizing the potential of international migration 142

D. Conclusions 146

Annex 3 146

6. Promoting equality and social justice in a changing world 147

Key messages 148

A. Managing global trends through an equality lens 149

B. Reducing inequality within countries: what experience can teach us 152

1. Expanding people’s access to opportunity 153

a. Education: the great equalizer? 153

b. Investing in work 155

2. Promoting redistribution and strengthening social protection 157

a. The potential of progressive taxation 158

b. Strengthening social protection 159

3. The political economy of redistribution 162

4. Tackling prejudice and discrimination 164

C. Reducing inequality in an interconnected world 166

1. A crisis in multilateralism? 166

2. Revitalizing multilateralism to reduce inequality 168

References 171

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

VIII

BOXES

1.1 Improved data sources to measure income inequality 24

1.2 Trends in global income distribution 25

1.3 Brazil: the decline of income inequality and the uncertain road ahead 28

1.4 Group-based disadvantages: measuring inequality of opportunity 35

1.5 South Africa: promoting inclusion amidst record high inequality 36

1.6 The challenge of measuring who is being left behind 39

1.7 Socioeconomic status and the intergenerational transmission 44

of disadvantage

1.8 China: rising inequality alongside greater social mobility 47

1.9 The United States: opportunity “hoarding” among high-income households 49

1.10 Inequality and the rise of populism 51

2.1 United States of America: higher-education wage premiums atten 69

2.2 India: Harnessing the potential of digital technologies for more 76

inclusive development

3.1 Climate change and migration: what we know so far 87

3.2 Mitigation and adaptation: preventing and preparing for climate change 89

3.3 Climate change and poverty-environment traps 100

3.4 Tempering public reaction to rising fuel prices: a balancing act 102

4.1 China: bridging the rural-urban divide 113

4.2 Brazil’s planned capital: from a utopian vision to a cautionary tale 115

4.3 Viet Nam: small cities home to large share of urban poverty 117

4.4 Gated communities, symbols of exclusion 119

5.1 The place premium 135

5.2 Lending a helping hand: migrant networks 137

5.3 The women that stay behind 143

6.1 The viability of a universal basic income: the jury is still out 162

6.2 The Rohingya in Myanmar: citizenship denied on the basis of ethnicity 165

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

IX

FIGURES

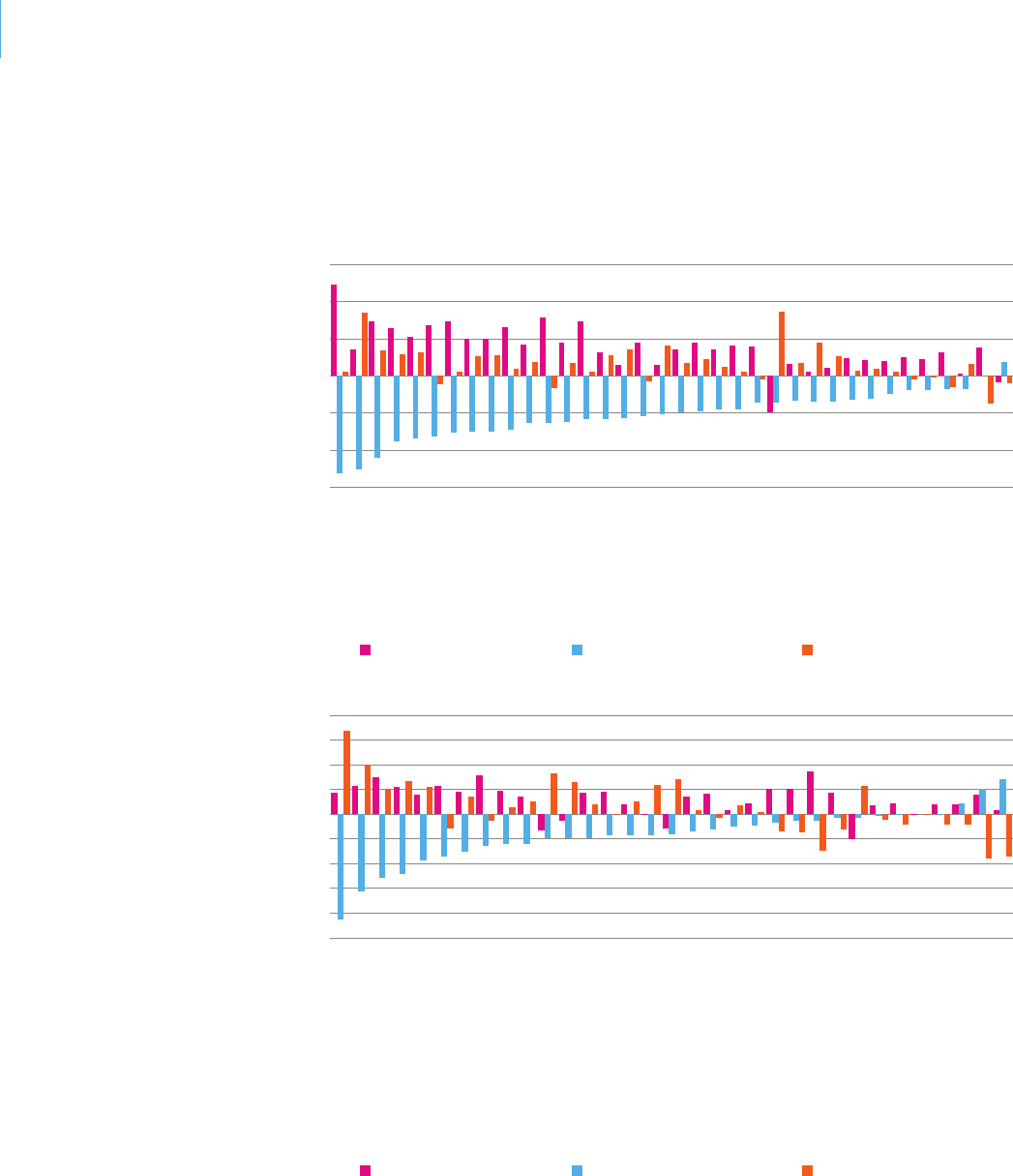

1.1 Mean incomes, top and bottom income deciles of selected 23

countries in 2015

B.1.1 Global growth incidence curve, 1988 to 2008 25

1.2 Share of income earned by the top 1 per cent, 1990 and 2015 30

1.3 Multidimensional poverty by ethnicity in selected countries 38

around 2010

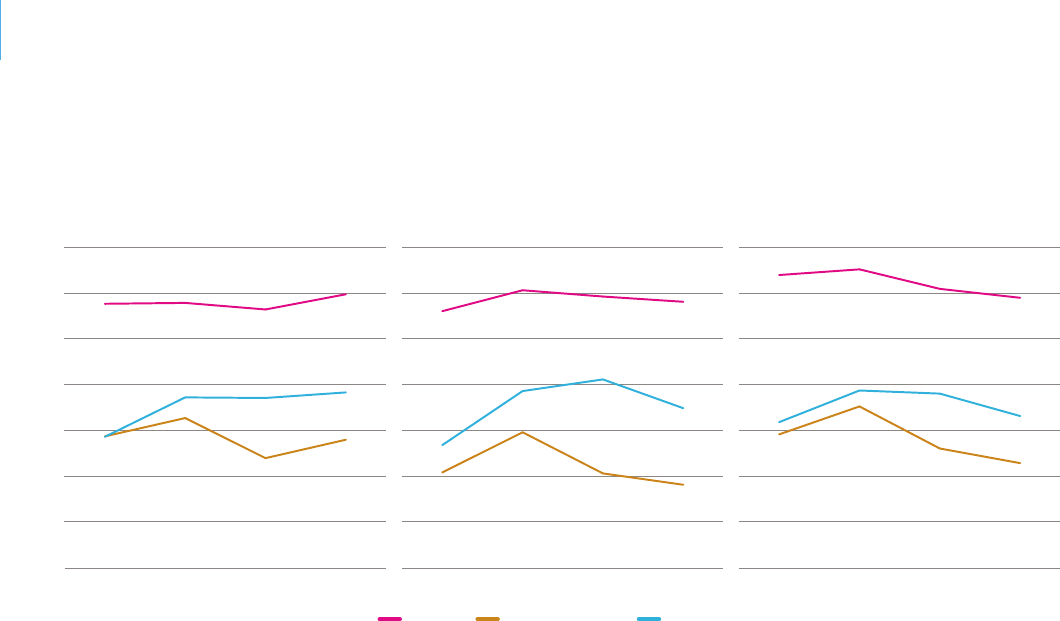

1.4 Recent trends in the proportion of stunted children by socioeconomic 41

status and ethnic group, 1990s to 2010s

1.5 Recent trends in secondary school attendance by socioeconomic 41

status and ethnic group, 2000s to 2010s

1.6 Prociency scores in mathematics, reading and science literacy, 42

by origin of student, 2009 to 2018

1.7 Percentage of adults who completed secondary or higher 43

education by disability status, 1990s to 2010s

1.8 Labour force participation rates by disability status, 1990s to 2010s 43

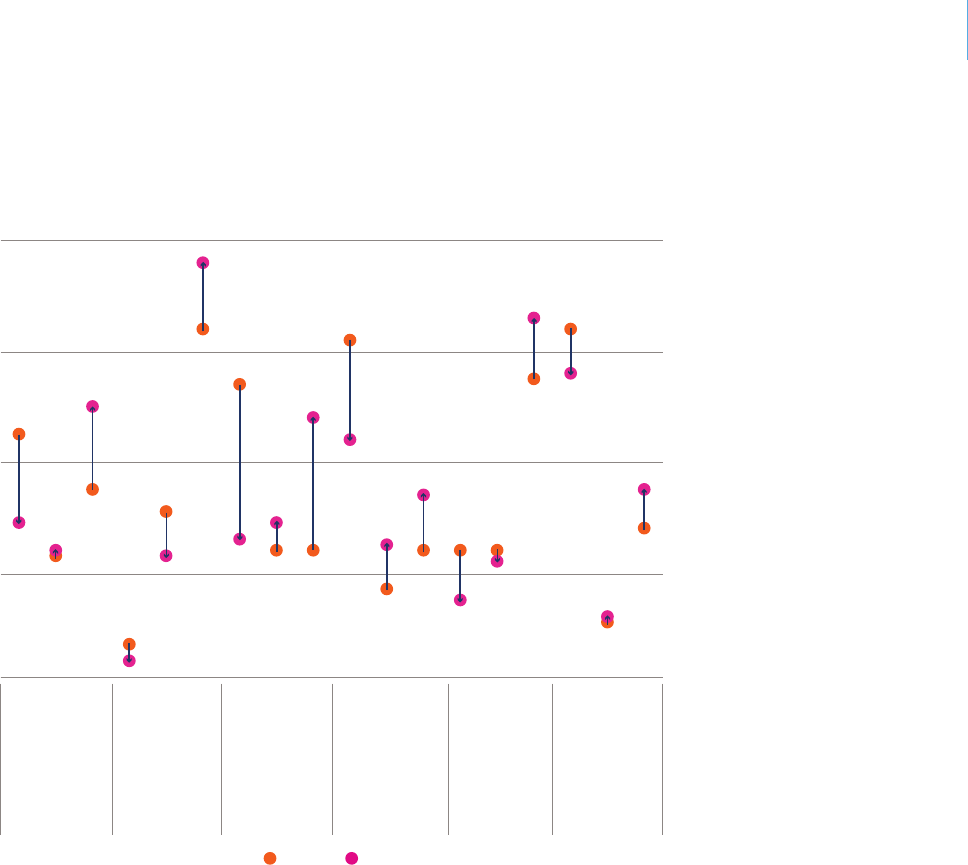

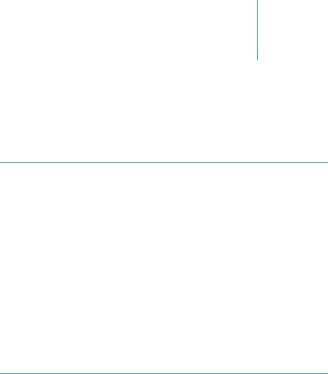

A.1.1 Recent trends in the proportion of households with access 56

to electricity, by household head characteristics, 1990s to 2010s

A.1.2 Recent trends in the proportion of households with access to improved 56

sanitation by household head characteristics, 1990s to 2010s

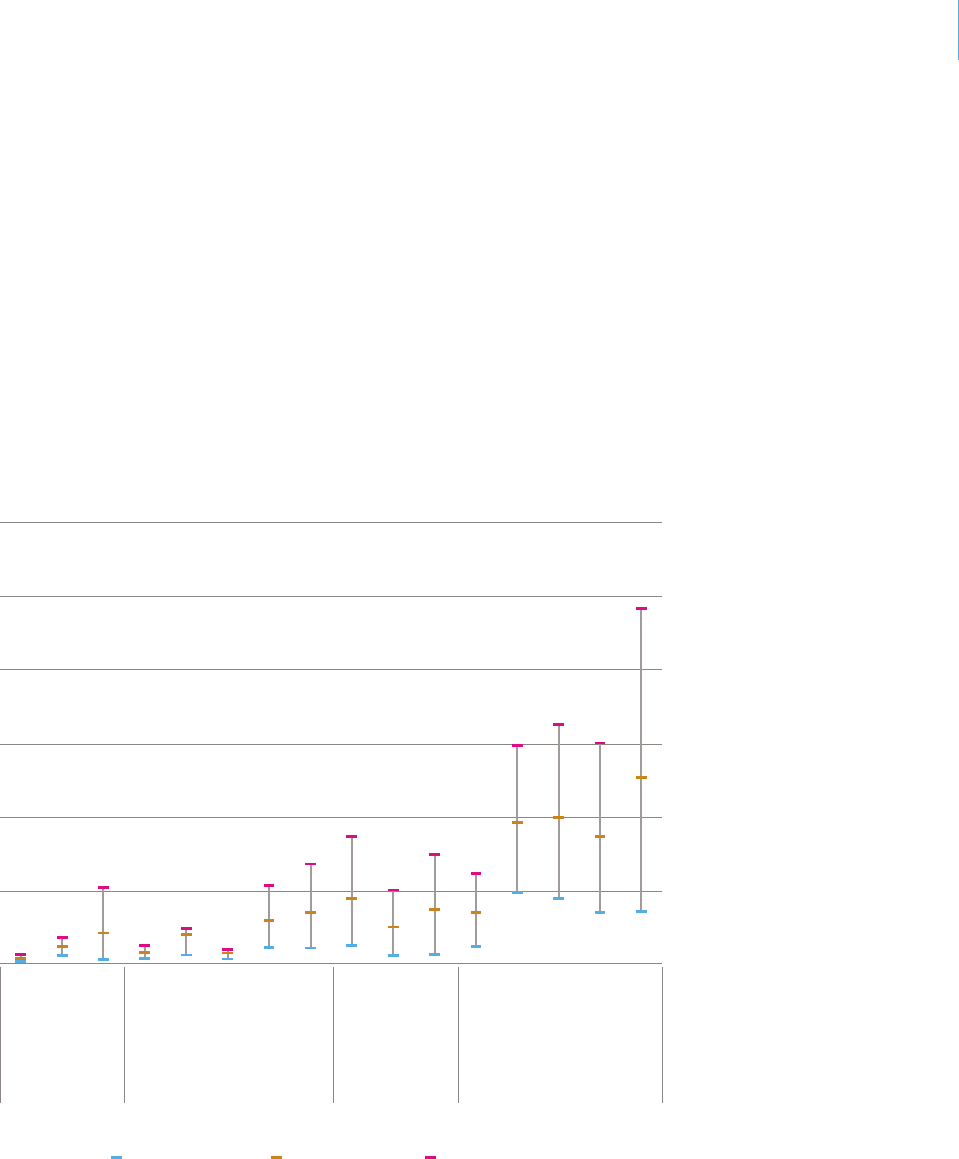

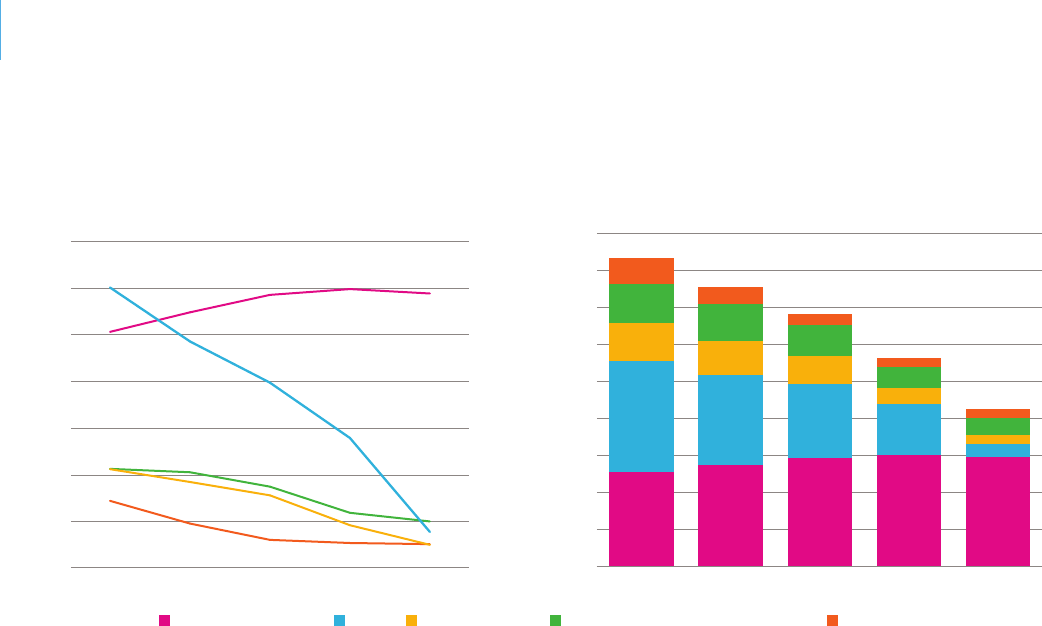

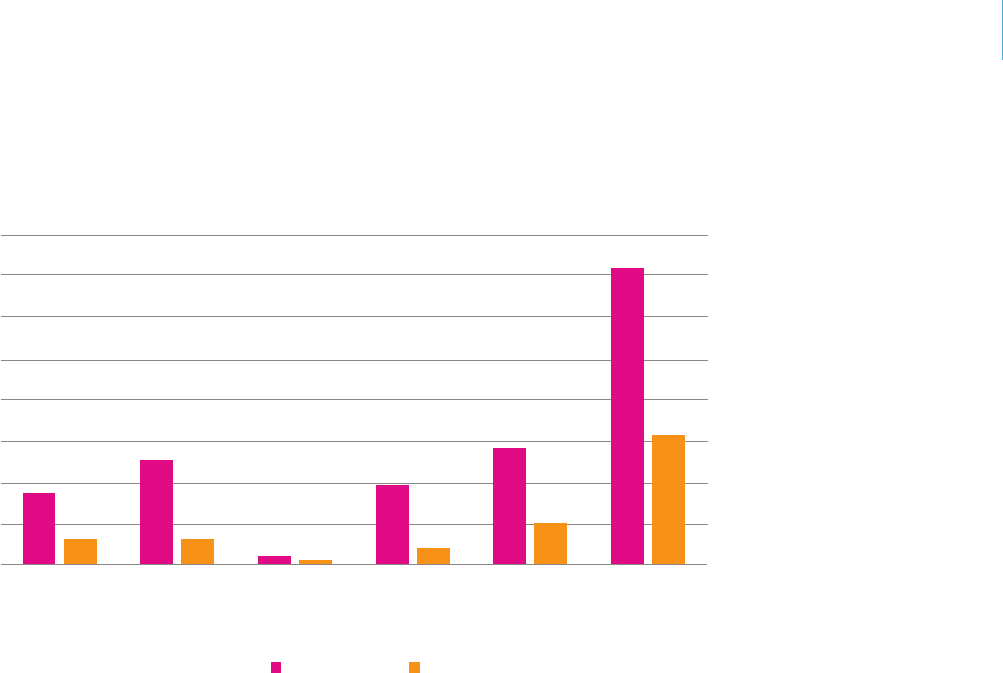

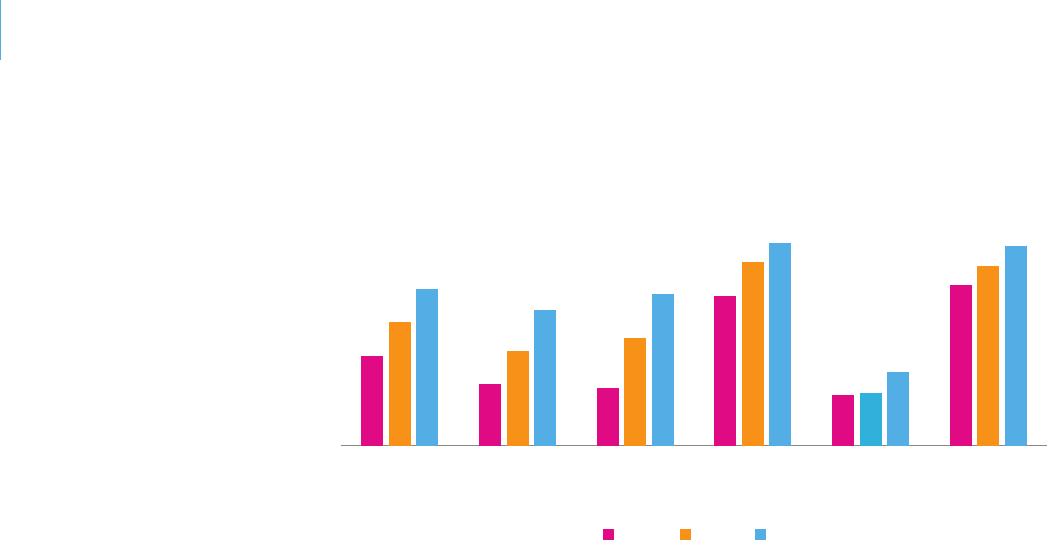

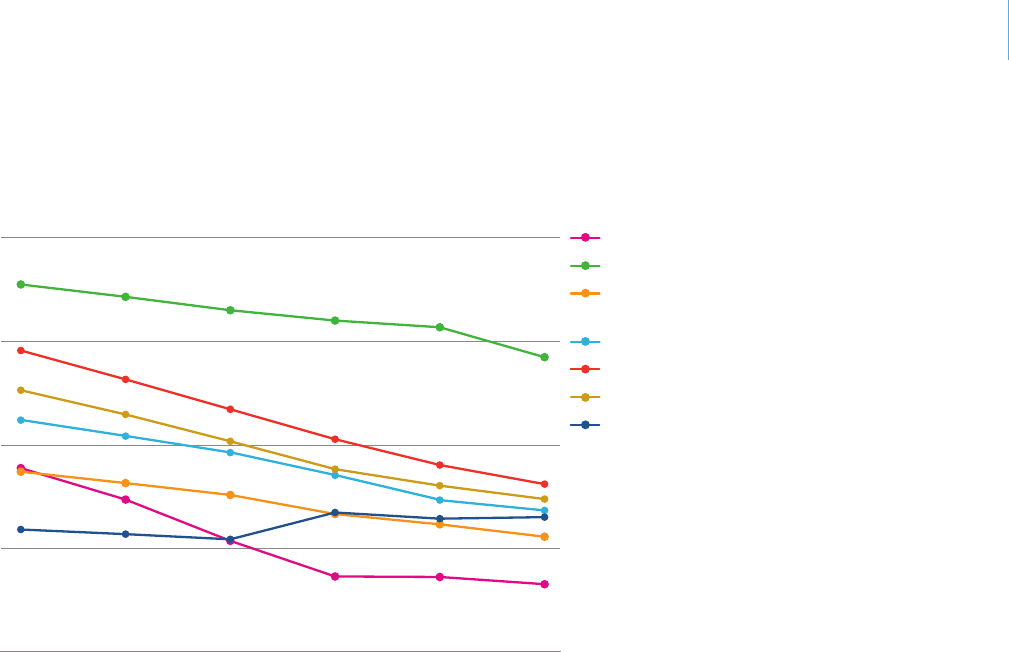

2.1 Total employment shares by sector and by region, 1991 and 2018 61

2.2 Wages by workers’ level of education relative to workers with 63

no degree, United States of America, 1980-2015

2.3 Polarization of labour markets: changes in employment shares by skill 66

level in high- and low-income countries, around 1995 and around 2015

2.4 Estimates of the share of jobs at risk of being lost to automation 70

as a result of articial intelligence and advanced technologies, by study

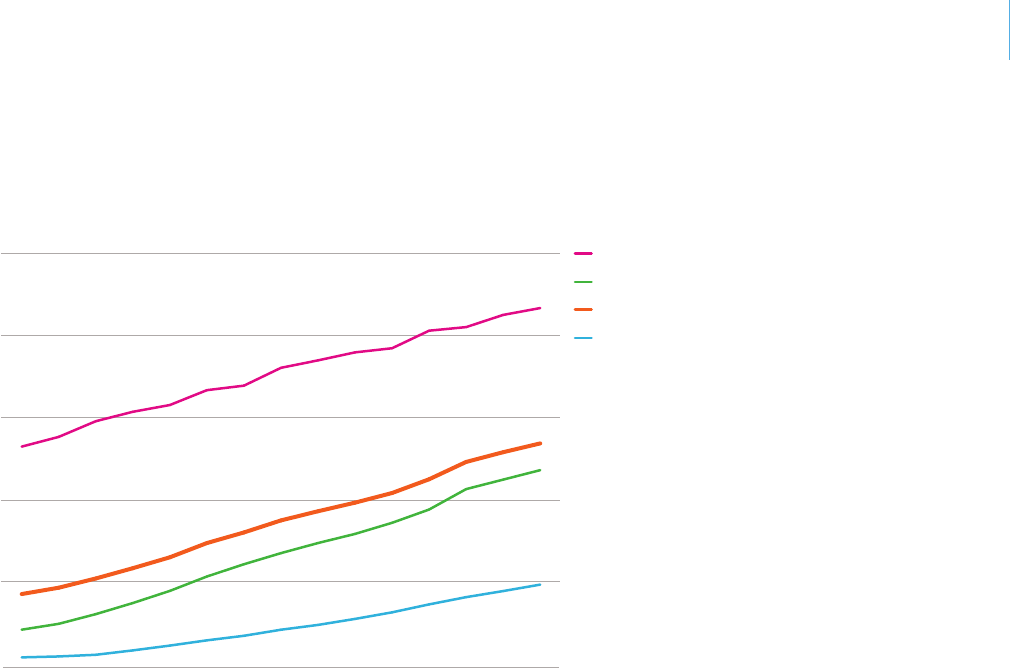

2.5 Levels and trends of people worldwide without access to electricity, 72

by selected countries and regions, 2000-2018

2.6 Percentage of the global population with access to the Internet 73

by country groupings, 2005-2017

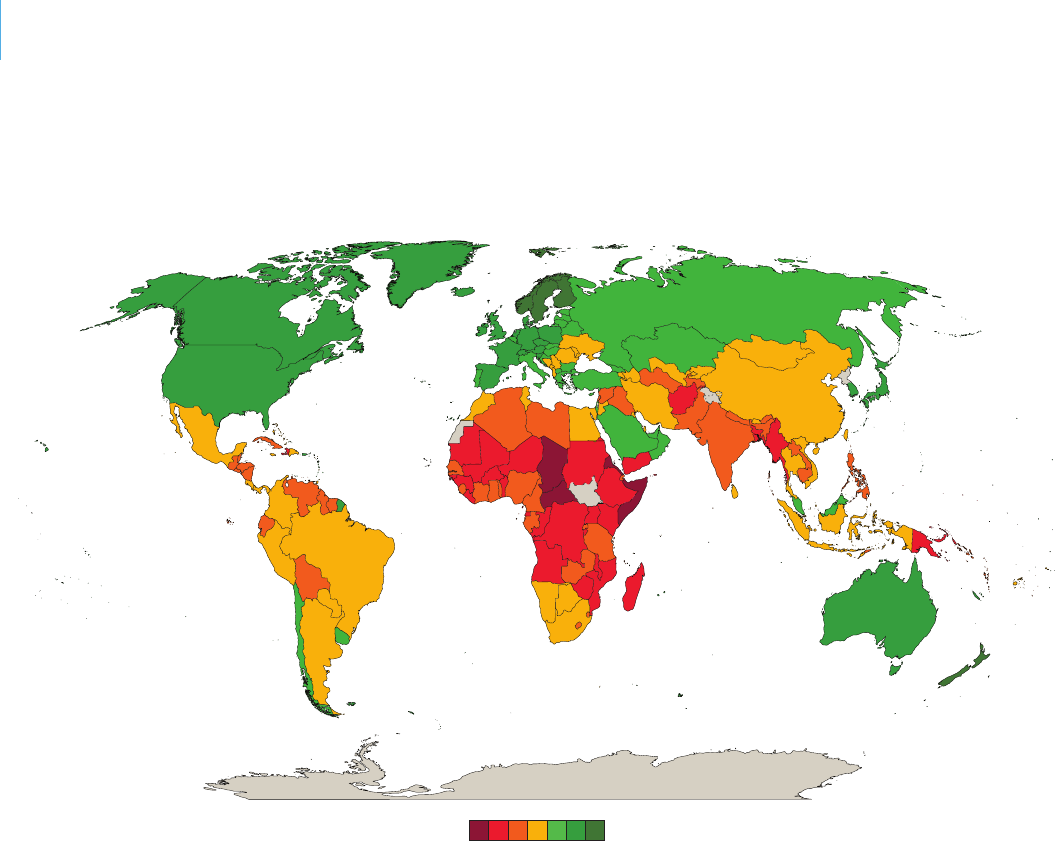

3.1 Climate risk by country, 2017 90

3.2 Climate-related economic losses by country income group, 1998-2017 92

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

X

4.1 Percentage of the population living in multidimensional poverty, 111

by region, 2018

4.2 Trends in four selected indicators of well-being for rural and 112

urban areas, 1990s to 2010s

4.3 Levels of urbanization in 1980, 2015 and projections to 2050 114

4.4 Proportion of urban population living in slums in developing 121

countries, 1990-2014

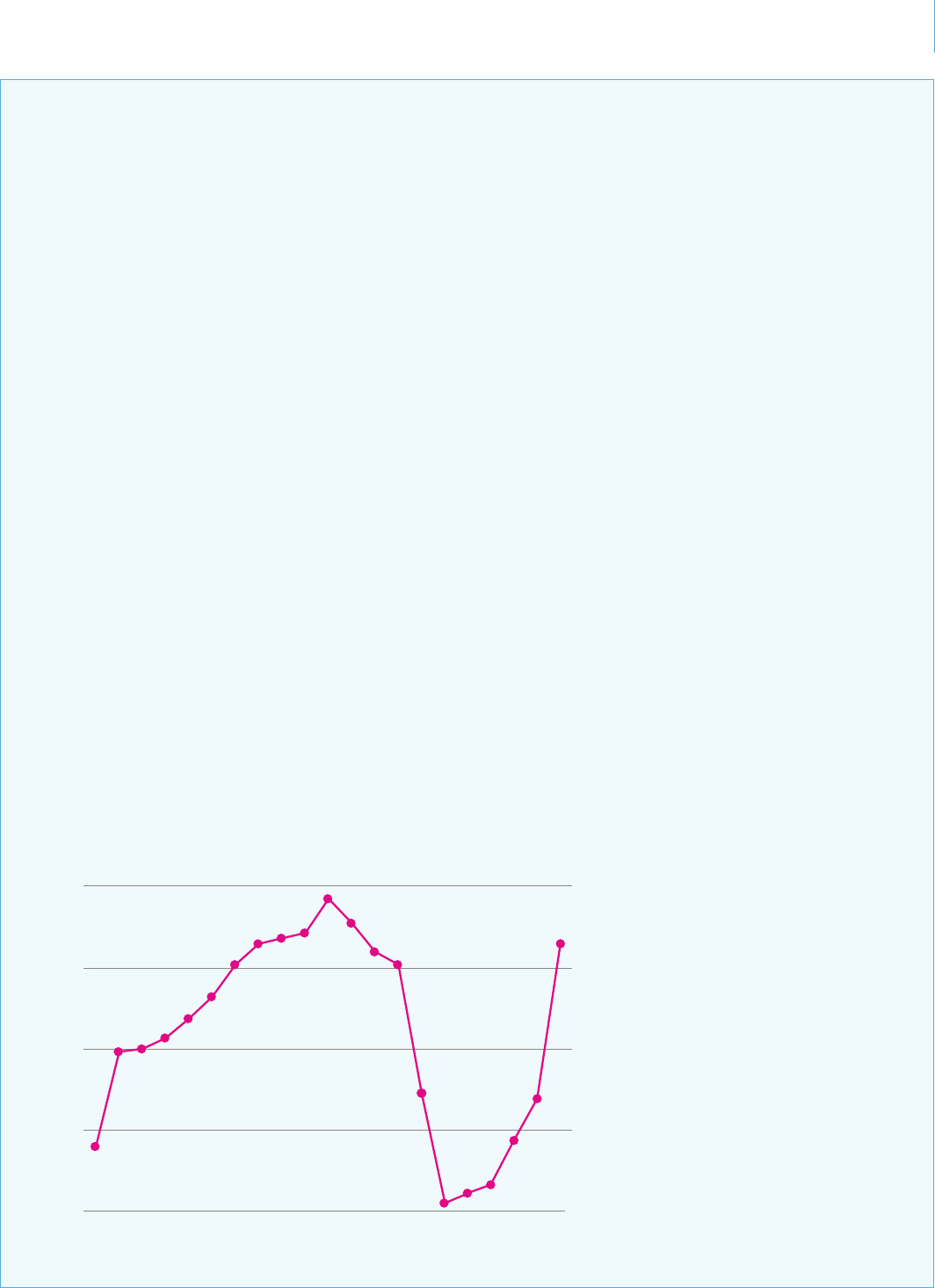

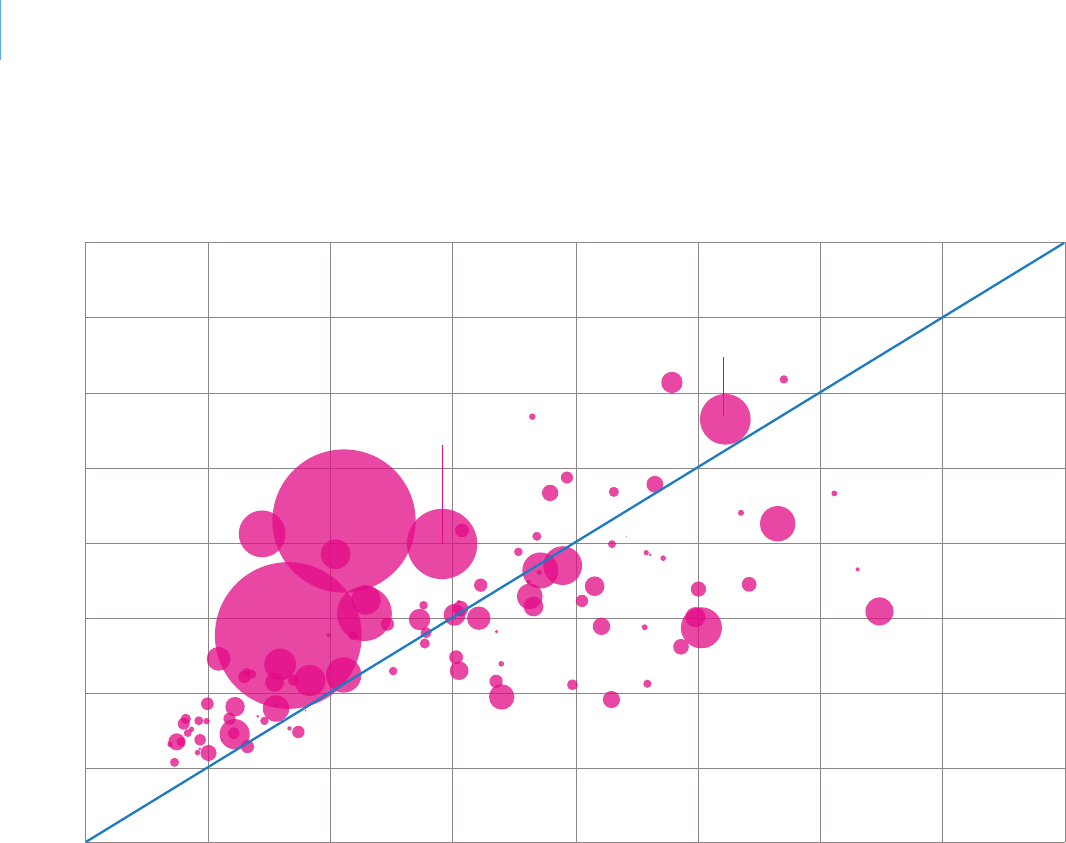

5.1 Migrants abroad by national income per capita, 2019 132

A.5.1 Emigration ratio by the Human Development Index of migrants’ 146

countries of origin, 2019

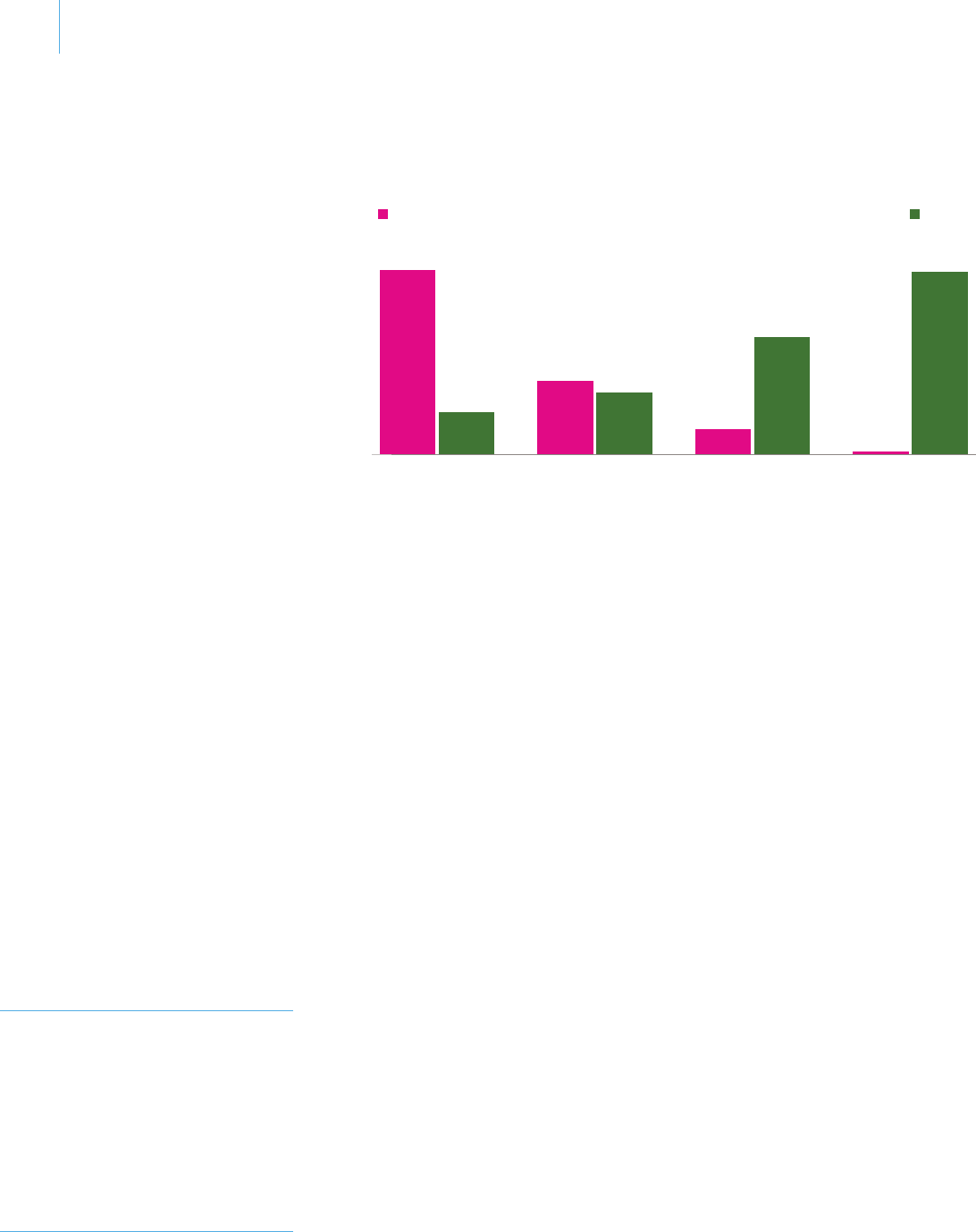

6.1 Impact of social insurance and social assistance programmes 160

on the Gini coecient of income in selected regions

6.2 Percentage of the global population with condence 167

in the United Nations

TABLES

1.1 Trends in income distribution by region, 1990 to 2016 27

2.1 Disparities in nancial account ownership by region, education, 74

income and gender, 2011-2017

3.1 Average ND-GAIN scores by country income group 91

4.1 Poverty share over proportion of total population by city size 116

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

XI

The following symbols have been used in tables throughout the report:

A hyphen (-) between years, for example, 1990-1991, signies the full period involved,

including the beginning and end years.

A full stop (.) is used to indicate decimals.

A dollars sign ($) indicates United States dollars, unless otherwise stated.

Details and percentages in tables do not necessarily add to totals, because of rounding.

When a print edition of a source exists, the print version is the authoritative one. United

Nations documents reproduced online are deemed ocial only as they appear in the

United Nations Ocial Document System. United Nations documentation obtained

from other United Nations and non-United Nations sources are for informational

purposes only. The Organization does not make any warranties or representations as to

the accuracy or completeness of such materials.

The following abbreviations have been used:

BEPS Base erosion and prot shifting

CRED Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters

DHS Demographic and Health Surveys

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

GDP Gross domestic product

GNI Gross national income

ICT Information and communication technologies

IEA International Energy Agency

ILO International Labour Organization

IMF International Monetary Fund

IOM International Organization for Migration

MICS Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys

MPI Multidimensional Poverty Index

ND-GAIN Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative

OECD Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

EXPLANATORY NOTES

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

XII

OPHI Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative

PISA Programme for International Student Assessment

PPP Purchasing power parity

SDGs Sustainable Development Goals

UBI Universal basic income

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

UN-HABITAT United Nations Human Settlements Programme

UN-ECLAC United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America

and the Caribbean

UN-ESCAP United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia

and the Pacic

UNESCO United Nations Educational Scientic and Cultural Organization

UNEP United Nations Environment Programme

UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

UNISDR United Nations Oce for Disaster Risk Reduction

UNU-WIDER United Nations University World Institute for Development

Economics Research

WID World Inequality Database

WIID World Income Inequality Database

WHO World Health Organization

WMO World Meteorological Organization

For analytical purposes, countries are classied as belonging to either of two categories:

more developed or less developed. The less developed regions (also referred to as

developing countries in the report) include all countries in Africa, Asia (excluding Japan),

and Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as Oceania, excluding Australia and New

Zealand. The more developed regions (also referred to as developed countries in the

Report) comprise Europe and Northern America, plus Australia, Japan and New Zealand.

The group of least developed countries comprises 47 countries: Afghanistan, Angola,

Bangladesh, Benin, Bhutan, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia, Central African Republic,

Chad, Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia,

Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, Kiribati, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Lesotho, Liberia,

Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Niger, Rwanda,

Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, Somalia, South Sudan,

Sudan, Timor-Leste, Togo, Tuvalu, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Vanuatu, Yemen

and Zambia. These countries are also included in the less developed regions.

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

XIII

This report uses the following country groupings or sub groupings:

Sub-Saharan Africa, which comprises the following countries: Angola, Benin, Botswana,

Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cabo Verde, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad,

Comoros, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Equatorial

Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau,

Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mayotte,

Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Réunion, Rwanda, Saint Helena, Sao Tome and

Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Togo,

Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Northern Africa, which comprises the following countries and areas: Algeria, Egypt,

Libya, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia, Western Sahara.

Central Asia, which comprises the following countries: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan,

Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan.

Eastern Asia, which comprises the following countries and areas: China, Hong Kong

Special Administrative Region, China, Macao Special Administrative Region, China,

Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Japan, Mongolia, Republic of Korea.

South-Eastern Asia, which comprises the following countries: Brunei Darussalam,

Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia, Myanmar,

Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Viet Nam.

Southern Asia, which comprises the following countries: Afghanistan, Bangladesh,

Bhutan, India, Islamic Republic of Iran, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka.

Western Asia, which comprises the following countries and areas: Armenia, Azerbaijan,

Bahrain, Cyprus, Georgia, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi

Arabia, State of Palestine, Syrian Arab Republic, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Yemen.

Eastern Europe, which comprises the following countries and areas: Belarus, Bulgaria,

Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Russian Federation,

Slovakia, Ukraine.

Northern Europe, which comprises the following countries and areas: Åland Islands,

Channel Islands, Denmark, Estonia, Faeroe Islands, Finland, Guernsey, Iceland, Ireland,

Isle of Man, Jersey, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Sark, Svalbard and Jan Mayen Islands,

Sweden, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Southern Europe, which comprises the following countries and areas: Albania, Andorra,

Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Gibraltar, Greece, Holy See, Italy, Malta, Montenegro,

North Macedonia, Portugal, San Marino, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain.

Western Europe, which comprises the following countries and areas: Austria, Belgium,

France, Germany, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Monaco, Netherlands, Switzerland.

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

XIV

Northern America, which comprises the following countries and areas: Bermuda,

Canada, Greenland, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, United States.

Latin America and the Caribbean, which comprises the following countries and areas:

Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Aruba, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bolivia

(Plurinational State of), Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba, Brazil, British Virgin Islands,

Cayman Islands, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Curaçao, Dominica, Dominican

Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Falkland Islands (Malvinas), French Guiana, Grenada,

Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Martinique, Mexico,

Montserrat, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Saint Barthélemy, Saint

Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Martin (French part), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines,

Sint Maarten (Dutch part), Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Turks and Caicos Islands,

United States Virgin Islands, Uruguay, Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of).

Oceania, which comprises the following countries and areas: Australia, American

Samoa, Cook Islands, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Micronesia

(Federated States of), Nauru, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Niue, Northern Mariana

Islands, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu,

Vanuatu, Wallis and Futuna Islands.

The group of small island developing States includes 58 countries or territories located

in the Caribbean (29), the Pacic (20), and the Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Mediterranean

and South China Sea (AIMS) (9). Further information is available at http://unohrlls.org/

about-sids/.

For the current 2020 scal year, low-income economies are dened as those with a

GNI per capita, calculated using the World Bank Atlas method, of $1,025 or less in

2018; lower middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita between $1,026

and $3,995; upper middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita between

$3,996 and $12,375; high-income economies are those with a GNI per capita of $12,376

or more:

Low-income economies: Afghanistan, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Central African

Republic, Chad, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Democratic Republic of the

Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, Liberia, Madagascar,

Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Nepal, Niger, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan,

Syrian Arab Republic, Tajikistan, Togo, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Yemen.

Lower-middle-income economies: Angola, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Bolivia (Plurinational

State of), Cabo Verde, Cambodia, Cameroon, Comoros, Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti,

Egypt, El Salvador, Eswatini, Ghana, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Kiribati,

Kyrgyzstan, Lao People's Democratic Republic, Lesotho, Mauritania, Micronesia

(Federated States of), Mongolia, Morocco, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Pakistan,

Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Republic of Moldova, São Tomé and Principe, Senegal,

Solomon Islands, State of Palestine, Sudan, Timor-Leste, Tunisia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan,

Vanuatu, Viet Nam, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

XV

Upper-middle-income economies: Albania, Algeria, American Samoa, Argentina, Armenia,

Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belize, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, China,

Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Equatorial Guinea,

Fiji, Gabon, Georgia, Grenada, Guatemala, Guyana, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Iraq,

Jamaica, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Lebanon, Libya, Malaysia, Maldives, Marshall Islands,

Mauritius, Mexico, Montenegro, Namibia, Nauru, North Macedonia, Paraguay, Peru,

Romania, Russian Federation, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa,

Serbia, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Suriname, Thailand, Tonga, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu,

Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of).

High-income economies: Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Australia, Austria,

Bahamas, Bahrain, Barbados, Belgium, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Brunei

Darussalam, Canada, Cayman Islands, Channel Islands, Chile, Croatia, Curaçao,

Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Faroe Islands, Finland, France, French Polynesia,

Germany, Gibraltar, Greece, Greenland, Guam, Hong Kong, SAR of China, Hungary,

Iceland, Ireland, Isle of Man, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kuwait, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania,

Luxembourg, Macao, SAR of China, Malta, Monaco, Netherlands, New Caledonia, New

Zealand, Northern Mariana Islands, Norway, Oman, Palau, Panama, Poland, Portugal,

Puerto Rico, Qatar, Republic of Korea, San Marino, Saudi Arabia, Seychelles, Singapore,

Sint Maarten (Dutch part), Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Sweden,

Switzerland, Taiwan, Province of China, Trinidad and Tobago, Turks and Caicos Islands,

United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, United

States of America, United States Virgin Islands, Uruguay.

Disclaimers for map in Figure 3.1:

The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not

imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the

United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its

authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed

upon by India and Pakistan. The nal status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been

agreed upon by the parties.

Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not

yet been determined.

A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom

of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning sovereignty over the Falkland

Islands (Malvinas).

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

XVI

QUOTE

1

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

Fifteen years ago, the Report on the World Social Situation 2005 warned that growing

inequality could jeopardize the achievement of internationally agreed development

goals. The report noted that the world was at a crossroads. If the vision of a shared

future was to be carried forward, world leaders had to seize every opportunity to take

bold and decisive action to reduce inequality (United Nations, 2005).

Inequality has since moved to the forefront of the policy debate. “Leave no one behind”

is the rallying cry of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Reducing inequality

within and among countries is Goal 10 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) –

with good reason. The extraordinary economic growth and widespread improvements

in well-being observed over the last several decades have failed to close the deep divides

within and across countries.

Powerful economic, social and environmental forces are affecting inequality. The

implications of these global forces – or megatrends – are broad and varied. Some can

help equalize opportunities, while others are exerting mounting pressure on income

inequality, mainly through their effect on labour markets.

This report examines the impact of four such megatrends on inequality: technological

innovation, climate change, urbanization and international migration. Technological

change can be an engine of economic growth, offering new possibilities in health care,

education, communication and productivity. But it can also exacerbate wage inequality

and displace workers. The accelerating impacts of climate change are being felt around

the world, but the poorest countries and groups are suffering most, especially those

trying to eke out a living in rural areas. Urbanization offers unmatched opportunities,

yet cities nd poverty and wealth in close proximity, making high and growing levels

of inequality all the more glaring. International migration allows millions of people to

seek new opportunities and can help reduce global disparities, but only if it occurs

EXECUTIVE

SUMMARY

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

2

WHETHER THESE

MEGATRENDS

ARE HARNESSED

TO ENCOURAGE

A MORE EQUITABLE

AND SUSTAINABLE

WORLD, OR

ALLOWED TO

EXACERBATE

DISPARITIES

AND DIVISIONS,

WILL LARGELY

DETERMINE THE

SHAPE OF OUR

COMMON FUTURE

under orderly and safe conditions. While these megatrends and the policies aimed at

managing them interact with each other in multiple ways, the focus of this report is

exclusively on the direct effect of each megatrend on inequality.

Whether these megatrends are harnessed to encourage a more equitable and

sustainable world, or allowed to exacerbate disparities and divisions, will largely

determine the shape of our common future.

INEQUALITY: WHERE WE STAND TODAY

For the rst time within the context of internationally agreed development goals, the

2030 Agenda includes targets to reduce inequality based on income.

Income inequality has increased in most developed countries and in some middle-income

countries, including China and India, since 1990. Countries where inequality has grown

are home to more than two thirds (71 per cent) of the world population. Yet growing

inequality is not a universal trend. The Gini coecient of income inequality has declined

in most countries of Latin America and the Caribbean and in several African and Asian

countries over the last two decades.

Despite progress in some countries, income and wealth are increasingly concentrated

at the top. The share of income going to the richest 1 per cent of the population

increased in 59 out of 100 countries with data from 1990 to 2015.

1

Meanwhile,

the poorest 40 per cent earned less than 25 per cent of income in all 92 countries

with data (United Nations, 2019a).

While economic inequality has grown within many countries, inequality among countries

is declining in relative terms. Strong economic growth in China and other emerging

economies in Asia has been the main driver of this decline. However, this convergence

is not evenly distributed, and the differences among some countries and regions are

still considerable. The average income of people living in Northern America is 16 times

higher than that of people in sub-Saharan Africa, for example. Meeting the targets

and Goals of the 2030 Agenda “for all nations and peoples” requires reducing these

stark disparities.

The 2030 Agenda also calls for ensuring equal opportunity and draws attention to

attributes and circumstances that affect access to opportunity, namely age, sex,

Two thirds of the world’s population live

in countries where inequality has grown

1

World Inequality Database. Available at https://wid.world/data (accessed on 6 November 2019).

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

3

disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion and economic or other status. While high and

growing income inequality is fuelling polarized political debates around the globe, a

consensus has indeed emerged that all should enjoy equal access to opportunity – that

one’s chances to succeed in life should not be determined by circumstances beyond an

individual’s control.

Major progress in fullling basic needs – through improved child health and increased

completion of primary education, for example – has moderated inequalities among

some population groups. However, unless progress accelerates, children from those

groups that are furthest behind will remain behind by 2030. At the rate of progress

observed from the 1990s to the 2010s, it will take more than four decades to close the

stunting gap related to ethnicity, for instance.

Evidence suggests that gaps in more advanced accomplishments persist or are

widening. For example, disparities in secondary school attendance by ethnic group,

wealth quintile and educational level of the household head have increased since the

1990s in developing countries with data.

2

Gaps in learning outcomes are large and

persistent as well.

Such inequalities have historical roots, but often continue even after the conditions that

generated them change. Ethnic minorities, for instance, often remain disadvantaged

even in countries where special efforts are made to promote their inclusion. Members

of groups that suffered from discrimination in the past start off with fewer assets

and lower levels of social and human capital than other groups. While prejudice and

discrimination are decried around the globe, they remain pervasive obstacles to equal

opportunity – and to the achievement of the SDGs.

Highly unequal societies are less effective at reducing poverty than those with low

levels of inequality. They also grow more slowly and are less successful at sustaining

economic growth. Disparities in health and education make it challenging for people to

break out of the cycle of poverty, leading to the transmission of disadvantage from one

generation to the next.

2

Calculations based on Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) data. For more

information, see chapter 1 of this report.

At the rate of progress observed from

the 1990s to the 2010s, it will take more

than four decades to close the stunting

gap between ethnic groups

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

4

Without appropriate policies and institutions in place, inequalities concentrate political

inuence among those who are already better off, which tends to preserve or even widen

opportunity gaps. Growing political inuence among the more fortunate erodes trust in

the ability of Governments to address the needs of the majority. This lack of trust, in

turn, can destabilize political systems and hinder the functioning of democracy. Today,

popular discontent is high even in countries that have fully recovered from the 2008

nancial and economic crisis and have beneted from steady growth in recent years.

Yet rising inequality is not inevitable. Inequality levels and trends differ among countries

that are at similar levels of development and equally exposed to trade, technological

innovation and even the effects of climate change. National policies and institutions

do matter.

THE TECHNOLOGICAL REVOLUTION:

WINNERS AND LOSERS

The world is in the midst of rapid, revolutionary and often disruptive technological

breakthroughs. Advances in biology and genetics, robotics and articial intelligence,

3D printing and other digital technologies are transforming economies and societies,

with unfolding and often unforeseen consequences.

For all its promise, technological change tends to create winners and losers. And

its current pace brings new and urgent policy challenges for navigating uncharted

territories. Much depends on how these policies play out, especially on the degree to

which Governments and international institutions address distributional effects and

maximize the benets and opportunities that new technologies can bring.

In the world of work, emphasis has focused largely on the potential implications of

technological change for job destruction. Yet technologies usually replace specic

tasks, rather than entire jobs. Often ignored is the fact that new technologies also

generate new jobs and tasks, including those necessary to use, test, supervise and

market new products and services.

At present, important differences are found across countries in how jobs are being

redesigned and tasks regrouped into new or existing jobs. Whether the automation of

tasks inevitably leads to the disappearance of jobs is as much a technological question

as it is an institutional one. Regulations and institutions inuence the protability of

regrouping tasks into new jobs and the ability of workers to upgrade their skills to take

on new responsibilities.

So far, highly skilled workers are beneting the most from new technologies.

Job disruption – and, at times, destruction – is affecting mainly low-skilled and

middle-skilled workers in routine manual and cognitive tasks. Moreover, in many

countries, the extraordinary gains brought about by new technologies are being

FOR ALL

ITS PROMISE,

TECHNOLOGICAL

CHANGE TENDS TO

CREATE WINNERS

AND LOSERS, AND

ITS CURRENT PACE

BRINGS NEW AND

URGENT POLICY

CHALLENGES

RISING INEQUALITY

IS NOT INEVITABLE.

NATIONAL POLICIES

AND INSTITUTIONS

DO MATTER

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

5

captured by a small number of dominant companies. If these trends continue,

they will lead to even greater polarization of the labour force, with less demand for

middle-skilled workers. They will also intensify wage inequality.

Automation has led to a reduction in jobs in routine-intensive occupations and is

likely to continue affecting them. However, there is no solid evidence to suggest that

recent technological advances have led to massive increases in joblessness or that

they will make work obsolete. Where new technologies are pushing wage and income

inequality higher, they are doing so mainly through increasing workforce polarization

and non-standard working arrangements that often lack the benets and stability of

regular jobs.

Digital innovation and articial intelligence are opening up opportunities in sectors

such as education, health and banking, with far-reaching implications for equality.

The use of the Internet and mobile phones, for instance, is enabling more people

in developing countries to access nancial services. Open online courses can help

democratize access to education. Mobile health applications make health-care

delivery and monitoring systems available to underserved areas and populations.

Improvements in data availability brought about by new technologies can enhance

governance and facilitate participation, helping individuals and groups to voice their

opinions and organize on behalf of common causes.

The potential of new technologies to foster sustainable development can only be

realized, however, if everyone has access to them. Regrettably, new technologies are

reinforcing various forms of inequality and creating new “digital divides”. Close to 87

per cent of the population of developed countries have Internet access, compared to

19 per cent in the least developed countries.

3

Access to basic technologies such as

mobile phones has improved rapidly, but gaps in access to the Internet and computers

persist. The potential of new technologies is particularly strong for youth, but it can

also widen the divide between younger and older people.

The speed of diffusion is important. Given the comparative advantage that “rst

movers” enjoy in many sectors linked to new technologies, gaps in access can push

poorer countries and disadvantaged groups further behind. Many of the benets

3

ITU Statistics (International Telecommunication Union). Available at www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/stat/default.aspx.

Highly skilled workers

are beneting the most

from new technologies

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

6

UNADDRESSED,

CLIMATE CHANGE

WILL INCREASE

INEQUALITY

WITHIN COUNTRIES

AND MAY EVEN

REVERSE CURRENT

PROGRESS

IN REDUCING

INEQUALITY

AMONG COUNTRIES

from new technologies that developing countries could realize may not materialize if

Governments and leading rms, which are often located in developed countries, fail to

reduce barriers to the entry and diffusion of such technologies.

The deployment of new technologies can exacerbate inequalities instead of reducing

them, even in contexts of broad accessibility. Gaps in education can widen, for

instance, if new technologies primarily benet those pursuing tertiary education,

or if they disproportionately improve the learning outcomes of children in wealthier

households.

In sum, as in any process of rapid structural change, technological innovation can

be disruptive. But its effects are not set in stone. Proactive policies and supportive

institutions can help ensure that technological dividends are broadly shared.

Three key policy interventions are called for. First, invest in skills that enable workers

to perform new tasks over a lifetime of changing work environments. Once-and-for-all

education at a young age is no longer sucient. Second, support people through work

and life transitions, including through universal access to social protection. Third,

strengthen efforts to bridge technological divides within and among countries.

CLIMATE CHANGE: EXACERBATING POVERTY

AND INEQUALITY

Climate change is accelerating environmental degradation and increasing the

frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, among other impacts. The effects

of both gradual environmental degradation and sudden shocks, such as hurricanes

and oods, disproportionately affect vulnerable populations. Whether they impinge on

infrastructure, livelihoods, resources, health or even the loss of lives and homes, these

impacts are by no means uniform across countries or population groups.

Rising temperatures have adversely affected economic growth in countries located in

the tropics, which tend to be poorer than countries located in more temperate climate

zones. They have made the world’s poorest countries poorer. The ratio between the

income of the richest and poorest 10 per cent of the global population is 25 per cent

The ratio between the income of the

richest and poorest 10 per cent of the

global population is 25 per cent larger

than it would be in a world without

global warming

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

7

larger than it would be in a world without global warming (Diffenbaugh and Burke, 2019).

Unaddressed, climate change may even reverse current progress in reducing inequality

among countries.

Within countries, people living in poverty and other disadvantaged groups – including

indigenous peoples and small landholders – are disproportionately exposed to climate

change. A majority of people in these groups live in rural areas and are highly dependent

on agricultural, shing and other ecosystem-related income. Their lives and livelihoods

are nely attuned to environmental conditions that are now changing rapidly. People

living in poverty are also more affected by infectious and respiratory diseases that

climate change will aggravate. Similarly, they are more susceptible to damage from

climate change than their richer counterparts living in the same regions. Finally, they

have fewer resources to help them cope with and recover from both sudden- and

slow-onset effects of climate change.

Climate change is affecting both the prevalence and depth of poverty, thereby

contributing to inequality. It is making it harder for people to escape poverty and is

increasing their vulnerability to falling into poverty, due to price shocks caused by

sudden changes in agricultural production, natural disasters and environmentally

triggered health problems. Estimates suggest that even under a low-impact scenario

where powerful mitigation and adaption strategies are successful, between 3 million

and 16 million people will fall into poverty by 2030 because of climate change. Under

a high-impact scenario, those gures could rise to between 35 million and 122 million

(Hallegatte and others, 2016).

Climate change is also having an impact on intergenerational inequality. The

disruptions caused by climate change are likely to reduce the livelihood opportunities

of future generations, especially in countries hardest hit, and exacerbate downward

intergenerational mobility.

Climate action and the transition to green economies bring opportunities to reduce

poverty and inequality. Economic restructuring brought about by the greening of

economies will result in the loss of lower-skilled jobs in carbon-intensive sectors.

However, with carefully designed adaptation strategies, it can result in the creation of

many new jobs worldwide and overall net gains.

A just, equality-enhancing transition towards green economies calls for the integration

of climate action with macroeconomic, labour and social policies aimed at job creation,

skills development and adequate support for those who will be harmed. Policies

aimed at reducing poverty and inequality, in turn, can help reduce the negative effects

of climate change and provide the means for low-income households to engage in

environmentally sustainable livelihoods.

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

8

THE CURRENT

SPEED OF

URBANIZATION

IN DEVELOPING

COUNTRIES AND

ITS EFFECTS

ON INEQUALITY

MAKES URBAN

GOVERNANCE

AND ADEQUATE

PLANNING

INCREASINGLY

URGENT

URBANIZATION: EXPANDING OPPORTUNITIES

BUT DEEPER DIVIDES

Geography matters. Where people are born and live has a lasting inuence on their

opportunities in life. Access to safe drinking water, electricity, health care, good

schools, decent work and other goals envisioned in the 2030 Agenda have a clear

spatial dimension. Regional inequalities within countries are often larger than

inequalities among countries.

Disparities between rural and urban areas stand out. The rural-urban divide is closing

in some countries but widening in others. The gap in levels of stunting among

children, for instance, has declined in 35 out of 53 developing countries with data –

and has increased in the remaining 18 – since the 1990s. The difference between the

percentage of urban and rural residents that have access to electricity has increased

in 23 out of 55 countries with data.

4

For the rst time in history, more people now live in urban than in rural areas. Over the

next three decades, all population growth is expected to occur in cities which will also

draw in rural populations through migration. This transformation has implications for

every aspect of sustainable development, including inequalities. Cities are catalysts

for economic growth, innovation and employment. However, urban areas are more

unequal than rural areas. In most cities and towns, areas characterized by high levels

of wealth and modern infrastructure coexist with pockets of severe deprivation, often

side by side.

The urban divide has economic, social and spatial dimensions. Economically, the Gini

coecient of income is larger in cities than in rural areas in most developed and

developing countries. Socially, rapid urbanization has led to growing concerns about

deteriorating health conditions. Even if maternal and child health are generally better

in urban than in rural areas, they are at times worse in urban slums and other poor

neighbourhoods of cities than in rural areas. Unregulated land and housing markets

as well as poor urban planning can concentrate disadvantages in specic locations

and lead to a vicious cycle of exclusion and marginalization. Slums are the most

visible symptom of exclusion in divided cities. In 2016, one in four urban residents, or

over one billion people, lived in slums.

4

Calculations based on DHS and MICS data. For more information, see chapter 4 of this report.

Income inequality is usually larger

in cities than in rural areas

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

9

Yet levels of inequality and poverty vary greatly by city, even within a single country.

Although spatial segregation and exclusion, based on income, race, migratory status

or other factors, are common to many urban areas, cities are unique, with different

histories and patterns. Inequalities have increased in some as they have grown and

developed but have declined in others.

In an increasingly urban world, innovative planning and city management are essential

to reduce inequality and achieve all other development goals. Too often, Governments

merely react to urbanization once imbalances in the process have become blatant. The

current speed of urbanization, especially in poor countries, makes urban governance

and appropriate urban design and planning increasingly urgent.

Four components are found in successful policy approaches to reduce inequality

and promote inclusive cities. First, secure housing and land rights, with a focus on

meeting the needs of people living in poverty, and provide equitable public services.

Second, improve spatial connectivity and promote public transportation to facilitate

equal access to the opportunities and amenities that cities offer. Third, promote

access to decent work and formal employment. Fourth, strengthen the political and

administrative capacities of local governments to respond quickly to increasingly

complex challenges, including those related to climate change.

INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION: A FORCE FOR EQUALITY

UNDER THE RIGHT CONDITIONS

International migration is a powerful symbol of global inequality, whether in terms of

wages, opportunities or lifestyles. Millions of people move each year across countries

and continents to seek better job opportunities, study, marry, reunite with family

members or ee conict or natural disasters.

Migration does not arise only from inequality or failed development: middle-income

countries send more migrants abroad than low-income countries. In general,

migration takes off once countries have started to grow economically and develop.

Industrialization and urbanization have long been associated with massive

displacements of people, mostly from rural to urban areas, but also across countries. As

countries develop, more people have the economic means to migrate. Improvements

in education and access to ideas, information and affordable transportation often

increase the desire and opportunities to migrate.

International migration generally benets most migrants and their countries of origin

and destination. Yet its costs and benets are not shared evenly across countries

or within countries.

In countries of origin, benets accrue through remittances and other transfers by

migrant communities abroad. Remittances help to reduce the scale and severity of

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

10

poverty in these countries and even contribute to the reduction of inequality among

countries. Indeed, more than 75 per cent of ocially recorded remittances were

received by low- and middle-income countries in 2018 (World Bank, 2019a).

Findings on the impact of remittances within countries are less conclusive. Wealthier

and more skilled migrants send remittances less often than less skilled migrants, but

the amounts wealthier migrants send are larger. Households at the lower end of the

income distribution are disproportionately affected by the high transaction costs of

sending money. Countries that restrict the immigration of less-skilled workers reduce

the ow of remittances and their potential levelling effect.

The impact of migration on the labour markets of destination countries are at the

core of current public debate. Concerns have been voiced over the negative effects

of immigration on wages, based on the belief that migrants compete directly with

native-born workers. However, less-skilled migrant workers often accept jobs that

non-migrants are not willing to perform, including in agriculture, mining, construction

and domestic work. Where migrants compete with less-skilled natives, immigration

may indeed exert downward pressure on already low wages and push inequality

higher. On the other hand, where they offer skills that are in short supply and services

that non-migrants are not willing to provide, migrants may contribute to the smooth

functioning of the labour market and even have a positive effect on employment.

In developing regions, the emigration of skilled workers is a cause for concern. It

can lead to shortages of professionals with key skills, such as teachers, doctors

and nurses. It can hamper economic growth and essentially subsidize richer

countries with highly trained workers. But positive feedback effects are possible

as well. Migrants abroad and those who return can generate flows of knowledge,

foreign direct investment and trade. In China, India and the Republic of Korea, for

instance, migrants abroad and returnees have been a driving force in the growth

of the software industry and other high-tech manufacturing industries. Whether

the emigration of skilled workers constitutes a net loss or a net gain – including

through the flows of knowledge and investment it generates – depends on the

country of origin. However, it is safe to assume that countries of destination may

gain, even more than sending countries, from the inflow of skills. Skilled migration

may contribute to rising international inequality if high-income countries, typically

countries of destination, gain more than low-income countries.

The 2030 Agenda highlights the role that migration can play in reducing inequality.

Yet the equalizing effects of migration are far from guaranteed. To a large extent,

the degree to which developing countries – and migrants themselves – benefit from

migration, and whether migration reduces or exacerbates inequalities, depends on

the conditions under which migration takes place.

TO A LARGE

EXTENT, THE

BENEFITS FROM

MIGRATION

DEPEND ON

THE CONDITIONS

UNDER WHICH

IT TAKES PLACE

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

11

Most destination countries in developed regions encourage the admission of highly

skilled migrants while offering few avenues for the legal entry of less-skilled or

educated migrants. Offering legal pathways for migration to less-educated workers

can benet both developed and developing countries. Moreover, actively promoting

their integration and that of their families, through access to health care, education

and other services, can benet society at large. Establishing mechanisms for the

formal recognition of educational credentials earned abroad would also help increase

migrants’ contributions. In order to ll specic job gaps, Governments in destination

countries may also consider funding training in countries of origin. Doing so would

equip migrants for success in destination countries and prevent shortages of skills in

their countries of origin.

The high cost of transferring money prevents people in poverty from fully reaping

the benets of migration. Meeting the SDG target of reducing the transaction costs

of migrant remittances to less than 3 per cent of the amount sent and eliminating

remittance corridors with costs higher than 5 per cent by 2030 can help workers and

their families keep more of their earnings.

PROMOTING EQUALITY AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

IN A CHANGING WORLD

The 2030 Agenda recognizes that major challenges are interrelated and require

integrated solutions. Without decisive action to manage megatrends in a

strategic and coordinated way, the world will see inequalities widen. Conversely,

addressing inequalities now will allow us to seize opportunities presented by these

transformative changes for the world as a whole and protect disadvantaged groups

from falling further behind.

Policymaking through an equality lens

The megatrends examined in this report are having an impact on the reduction

of inequalities and on the achievement of all other SDGs. However, their course

is not set. It is neither possible nor desirable to hold back technological change,

urbanization or migration, but their effects can be managed to encourage more

equitable and sustainable societies. Climate change cannot be turned around in the

short term and has already exacted significant and possibly irreversible changes.

Still, social considerations can be part of adaptation and mitigation policies as

countries transition to green economies.

The evidence summarized in this report shows that these megatrends can be

managed in ways that ensure their benefits are broadly shared and their negative

effects do not fall disproportionately on those who lack the resources to cope and

recover. Applying an equality lens to policymaking calls for policies and regulations

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

12

that leverage the potential of new technologies to reduce poverty and create jobs

while addressing existing technological divides. It requires policies that build

the resilience of people living in poverty to climate change. It means addressing

the spatial, economic and social divides within cities, making urbanization more

inclusive and ensuring that rural areas are not left behind. And it calls for facilitating

safe, orderly and regular migration and promoting its positive impacts.

Applying an equality lens also means that Governments should reconsider policies

that aggravate the harmful effects of these trends. While technological change

may have contributed to workforce polarization and increased wage inequality,

for instance, financial and labour market deregulation, declines in income tax

progressivity and weakened social protection have also exacerbated these trends

in some countries.

Finally, applying an equality lens means redoubling efforts to address the root causes

of inequality now.

Reducing inequality within countries: what experience can teach us

Mixed success in reducing inequalities within countries calls for a rethinking of

strategies. Clearly, no single set of policies is applicable to all countries and contexts.

Instead, this report highlights three building blocks of a coherent and integrated policy

strategy to reduce inequality in many of its dimensions.

Promote equal access to opportunities

Universal access to quality education, in particular, expands opportunities and

encourages a more equal distribution of capabilities. However, the educational system

has often served to reinforce inequalities rather than help to level the playing eld.

Supporting people in realizing their potential also requires the promotion of full

employment and decent work. Yet the contrast between looming and transformative

changes in the world of work and the preparedness of Governments and the international

community to manage them is stark. Governments can address these disconnects by

increasing investments in labour market institutions and policies and supporting new

forms of collective representation, ensuring that those who work under non-standard

employment contracts or outside the formal sector have a voice.

Institute a macroeconomic policy environment conducive to reducing inequality

Fiscal and monetary policies can encourage greater equity. In addition to their direct

impact on income distribution, they can also mobilize resources for social policies,

including social protection. The way in which taxes and expenditures are allocated is at

the heart of the social contract.

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

13

Universal access to effective social protection goes a long way towards reducing

poverty and inequality, as substantiated by the evidence presented in this report. Social

protection systems that provide unemployment and disability benets, child benets,

old-age pensions and access to health care offer income security at all stages of

the life cycle and minimize the risk of falling into poverty. Despite the value of social

protection systems in building a more equitable society, comprehensive coverage

was enjoyed by only 29 per cent of the world population in 2017 (ILO, 2017a).

Tackle prejudice and discrimination and promote the participation of

disadvantaged groups in economic, social and political life

Social and economic policies will have limited impact on inequality if societies

continue to discriminate on the basis of ethnicity, race, gender or other characteristics

that should have no bearing on achievement or well-being.

Ending prejudice and discrimination is a long-term process. It requires reforming

institutions and inuencing social norms and behaviours. Constitutional changes,

revision of discriminatory laws and policies, and the passage of new laws to prevent

discrimination and promote the well-being of excluded groups can lay the groundwork

for greater fairness.

However, all of these measures tend to challenge the status quo, and thus are likely to

encounter resistance. In most cases, inaction is due not to the lack of sound technical

advice or even adequate capacity. Rather, mobilizing support for policy responses

that affect the balance of power can be most dicult. Understanding the political

constraints to reducing inequality and devising ways to overcome them is key to

breaking the current stalemate.

In general, policy frameworks grounded in universalism have enjoyed broader support

than those focused narrowly on addressing the symptoms of poverty or disadvantage.

While reducing inequalities may require measures targeted at specic groups to meet

their special needs, a universal policy framework is necessary to address the root

causes of inequality and ensure that policies enjoy sustained popular support.

Reducing inequality in an interconnected world

Governments and other national stakeholders are key players in creating more

equitable societies. But large gaps in well-being and opportunities within and among

countries are a national as well as a global problem, demanding integrated, multilateral

solutions. One country’s action on climate change or international migration – or lack

thereof – has costs and benets for other countries. The imbalance between top

greenhouse gas-emitting countries and those suffering the most from the impacts

of climate change is a well-documented injustice. None of these issues can be

addressed unilaterally. Concerted, coordinated and multilateral action is also needed

MOBILIZING

SUPPORT FOR

POLICY RESPONSES

TO INEQUALITY CAN

BE CHALLENGING

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

14

to address other challenges that affect inequality within and among countries, namely

tax evasion, cross-border nancial ows, transnational crime, international trade and

intellectual property rights.

At this critical juncture, however, multilateralism is under attack and trust in public

institutions is flagging. Although the multilateral system may need adjusting,

current global challenges call for strengthening it, rather than dismissing it altogether.

Among other things, restoring trust in international problem-solving requires

multilateral institutions that give adequate voice to regions and countries with growing

influence in the global economy as well as to those groups and communities that

are being left behind.

It is increasingly clear that reducing inequalities strengthens not only the social

fabric but also the economic and environmental dimensions of sustainable

development. However, this awareness has not yet been translated into the necessary

normative changes. Instead, growing inequalities and overreliance on the capacity

of markets to bring about social justice threaten the social contract in many countries.

Beyond the urgent need to accelerate action, realizing the vision of the 2030 Agenda

requires a reconsideration of the policy priorities that have perpetuated inequality

as well as insecurity.

LARGE GAPS IN

WELL-BEING AND

OPPORTUNITIES

WITHIN AND AMONG

COUNTRIES ARE

NATIONAL AS

WELL AS GLOBAL

PROBLEMS,

DEMANDING

INTEGRATED,

MULTILATERAL

SOLUTIONS

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

15

The year 2020 marks the twenty-fth anniversary of the World Summit for Social

Development and the fth anniversary of the adoption of the 2030 Agenda for

Sustainable Development. The commitments made by world leaders, and the

ideals they represent, are milestones in the international pursuit of greater equity

and non-discrimination They are also a rearmation of the vision chartered with

the founding of the United Nations 75 years ago. It was a vision based on “faith in

fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal

rights of men and women and of nations large and small”.

5

Heads of State and Government gathered once again in September 2019 to take stock

of how far countries have come in realizing their commitments. The voluntary national

reviews presented in advance of the United Nations Summit on the Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs) attest to the wide-ranging actions taken by Governments

and other stakeholders in responding to global challenges.

6

Yet, as the United Nations

General Assembly recognized in its declaration of the Summit, inequalities in wealth,

income and opportunities are increasing. Governments will need to do more and

faster in order to leave no one behind.

7

While the challenge is clear, there is far less consensus on what is fuelling these

trends and on what can be done to address them. Many of the factors driving

growing inequalities are specic to countries or regions based on their history,

geography, policies and institutions. At the same time, powerful economic, social

and environmental forces are also at play. The implications of these global forces –

or megatrends – are far-reaching and varied. While some are helping to equalize

INTRODUCTION

5

Preamble to the Charter of the United Nations (1945).

6

See: Note by the Secretariat: Compilation of main messages for the 2019 voluntary national reviews (E/HLPF/2019/5).

7

A/RES/74/4.

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

16

opportunities, others are exacerbating income inequality. Some are taking a toll on

the poorest countries and groups while others are solidifying the advantages of those

already better off.

This report examines the impact of four megatrends on inequality: technological

innovation, climate change, urbanization and international migration. Technological

change is an engine of economic growth offering new possibilities in health care,

education, communications and productivity. Yet it can also raise wage inequality

and displace workers. Climate change is affecting all countries, but it is hitting

the poorest countries and population groups the hardest, affecting most directly

people seeking to eke out a living in rural areas. Urbanization offers unparalleled

opportunities for poverty reduction, while rural areas remain disadvantaged in terms

of services, jobs and income in both developing and developed countries. Yet urban

areas are more unequal than rural areas and inequalities are rising in cities and

megacities around the world. International migration allows millions of people to

seek new opportunities and can help reduce global disparities, but only if it occurs

under safe and orderly conditions.

The 2030 Agenda recognizes that critical challenges facing the world today require

integrated solutions. It explicitly states that eradicating poverty in all its forms,

combating inequality within and among countries, preserving the planet, creating

sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, and fostering social

inclusion are interlinked and interdependent. Indeed, without decisive action to

manage each of these megatrends in a strategic and coordinated way, the world will

see inequalities widen. Conversely, addressing inequality now will help countries

seize the opportunities presented by these transformative changes, and protect

people living in poverty and other disadvantaged groups against their most

negative effects.

The report traces recent inequality trends. It discusses why inequality matters and

provides an overview of the impacts of each megatrend. In considering the effects

of technological innovation and of urbanization, the focus is on inequality within

countries. The report assesses the effects of climate change and of international

migration on inequality both among and within countries. These megatrends and

the policies aimed at managing them interact with each other in multiple ways.

Technological change, for instance, can help combat climate change. Unaddressed,

climate change will affect international migration trends. Even though these

multiple interactions require policy attention and analysis, the focus of this report is

exclusively on the direct effect of each megatrend on the distribution of resources

and opportunities.

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

17

While these trends are global, how each of them affects specic countries, communities

and population groups, immediately and over time, depends on the institutions and

policies in place. A key message of the report is that the effects of new technologies,

urbanization, international migration and even climate change on the distribution of

resources and opportunities are not predetermined. Some countries have managed to

protect the most vulnerable from the negative impacts of these trends while ensuring

that their benets are broadly shared. Despite constraints, there is still ample scope

for independent national policymaking to help harness these global forces for the

good. Policies can and should rectify trends that are neither socially, environmentally

or politically sound nor morally acceptable.

At the same time, global challenges call for global solutions. Actions taken by one

country affect other countries. Coordination and collective decision-making are

needed to manage the global commons and the international movement of people.

The evidence presented in this report arms the critical role of multilateral action to

address the driving forces of inequality under the global social contract embodied in

the 2030 Agenda.

WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2020

18

QUOTE

CHAPTER 1

INEQUALITY: WHERE

WE STAND TODAY

19

INEQUALITY IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

KEY MESSAGES

• Inequality within countries is very high but it is not rising everywhere. Since 1990,

income inequality has increased in most developed countries. Inequality declined in

most Latin American countries from 1990 to the early 2010s but is increasing again

in some of them.

• Inequality trends differ across countries at even similar levels of development.

• Income inequality among countries has declined in relative terms but is still higher

than inequality within most countries. Absolute income differences between countries

continue to grow.

• The world is far from the goal of equal opportunity for all: circumstances beyond

an individual’s control, such as gender, race, ethnicity, migrant status and, for

children, the socioeconomic status of their parents, continue to affect one’s chances

of succeeding in life.

• Group-based inequalities are declining in some cases but still growing in many others.

Unless progress accelerates, leaving no one behind will remain a still distant goal

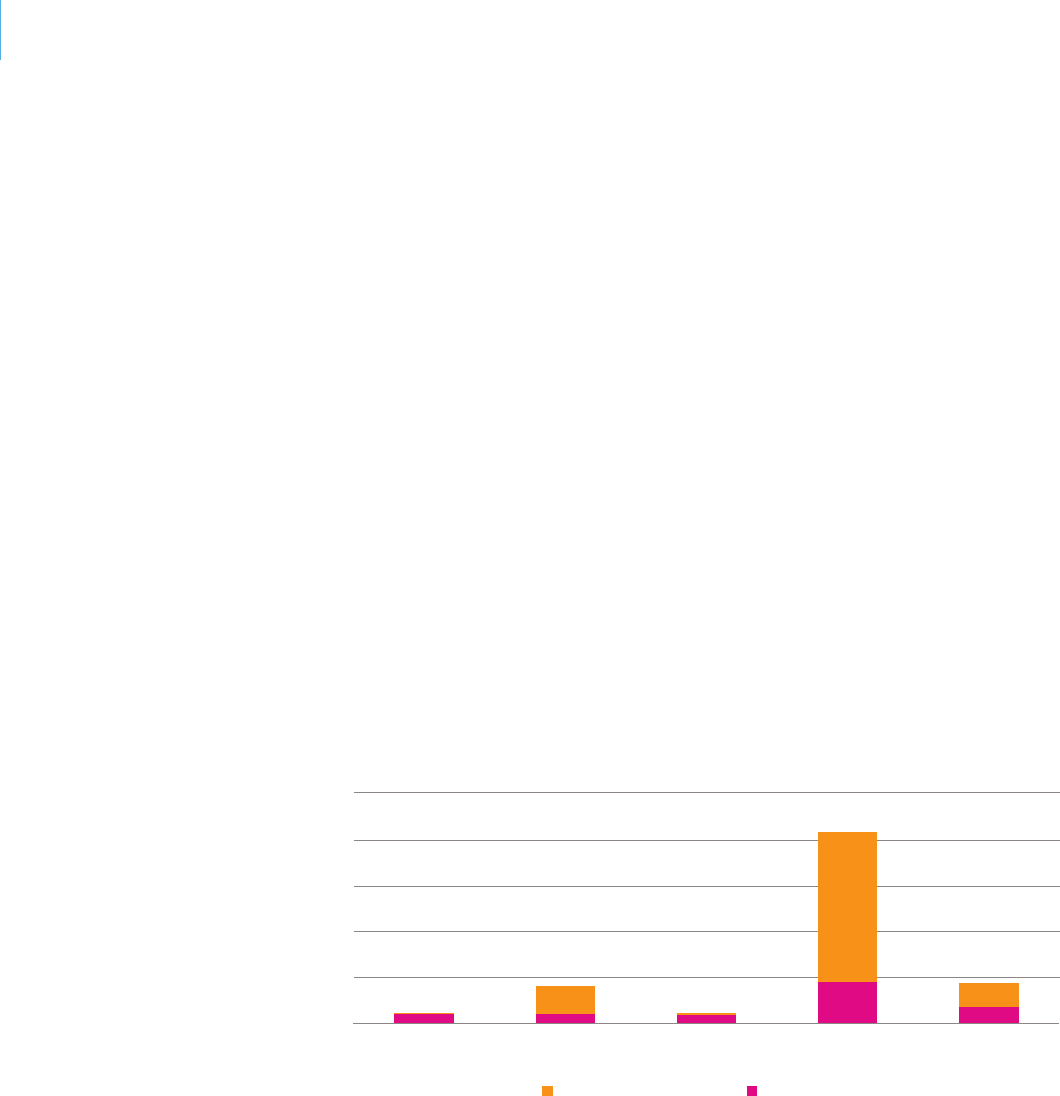

by 2030.