Food Sci. Technol, Campinas, v42, e94321, 2022 1

Food Science and Technology

ISSN 0101-2061 (Print)

ISSN 1678-457X (Online)

OI: D https://doi.org/10.1590/fst.94321

1 Introduction

Foodborne diseases (FBDs) are a major public health issue

worldwide, especially for young persons, older persons, and those

who are sick (Fungetal., 2018). e World Health Organization

(WHO) denes FBDs as ‘diseases causing the infection or

poisoning of human bodies, usually caused by pathogens that

enter bodies through ingestion (Guoetal., 2018). In China, the

most common pathogens of foodborne diseases are Dysentery

bacilli, Typhoid bacilli, Salmonella, Vibrio parahaemolyticus

and Escherichia coli. e peak incidence of those pathogens

mentioned above is concentrated from July to September. And the

peak incidence of norovirus was concentrated from November

to May of the following year (Fuetal., 2019;Wuetal., 2021).

Microbial contamination is an important cause of morbidity

and mortality.

According to a report by the WHO, in 2010, 600 million people

fell ill globally, and 420,000 people died from FBDs. e global

burden FBDs caused in 2010 was 33 million disability adjusted

life years(DALYs) (Havelaaretal., 2015). Internationally, one

of the most notorious incidents is the Minamata disease caused

by methylmercury poisoning, which, released from factories,

accumulated in sh and shellsh and entered the body through

consumption, rst discovered in 1956 in Kumamoto Prefecture,

Japan (Fungetal., 2018). Another incident occurred in the Jinzu

river basin, Japan. e local residents along the river suered

an illness called ‘itai-itai’. e river and crops were polluted by

the sewage discharged from mining. us, cadmium entered

the body through water and rice consumption. is caused

a series of symptoms, with ostealgia as the main symptom

(Fungetal., 2018).

On average, one in every 6.5 people in China suers from

FBDs due to eating unsafe food (Chen, 2016). Food safety issues

are also causing concern. In 1988, an outbreak of hepatitis A

occurred in Shanghai due to consumption of raw clams, which

resulted in nearly 300,000 people suering from illness, and

11 deaths (Liuetal., 2018). In 2008, consumption of melamine-

tainted milk had sickened more than 294,000 infants and young

children, of whom 51,900 were hospitalised and resulted in at

least six deaths, mainly due to kidney problems (El-Nezamietal.,

2013). In 2011, in Henan province in China, many farms fed pigs

with fodder mixed with clenbuterol for economic benets. Once

an anti-asthma drug, clenbuterol is banned in fodder because

it brings great harm to humans through the consumption of

pork (Huetal., 2019).

Unsafe food not only aects human health and security, but

also threatens economic growth and social stability.Food safety

was ranked rst in the top ve safety issues in China (Lametal.,

Surveillance for foodborne diseases in a sentinel hospital in Jinhua city, Midwest of

Zhejiang province, China from 2016–2019

Fang-Rong XU

1

, Yang YANG

2

*

a

Received 19 Sep., 2021

Accepted 20 Oct., 2021

1

Department of Clinical Nutrition, Aliated Jinhua Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Jinhua, Zhejiang, China

2

Department of Prevention and Health Care, Aliated Jinhua Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Jinhua, Zhejiang, China

*Corresponding author: yangyangyy[email protected]

Abstract

To analysis the main clinical symptoms and causative hazards of foodborne disease outbreaks to provide a reference for the

prevention, control, and early warning of foodborne diseases. 2,919 FBDs cases were collected and summarised through the

China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) surveillance system. Foodborne diseases were detected according to national

standards. Microso Excel 2010 and SPSS 12.0 were used for data descriptive analysis. e mean±standard deviation was used

to describe the numerical variables, and the frequency and composition ratio were used to describe the classication variables.

ere were 2,919 FBDs cases included in the analysis. e highest number of cases occurred among students (41.49%) and

farmers (22.85%). e months of August (398,13.63%), September (333,11.41%) and July (330,11.31%) accounted for most cases.

e two most frequent pathogens supported by laboratory conrmation are Norovirus and Salmonella. e major symptoms

of illness were diarrhoea (97.64%), fever (27.95%), abdominal pain (24.67%), vomiting (22.30%), and nausea (13.7%). is

study revealed epidemiological characteristics of FBDs and identied some higher risk factors for interventions. Salmonella

and Norovirus were the main pathogens. Foods from catering service settings and animal foods were the factors most likely to

contribute to foodborne diseases. Most cases of intoxication and outbreaks were related to wild mushrooms.

Keywords: foodborne diseases; surveillance; epidemiology; risk factors.

Practical Application: is article provided clues for health education of community oriented, school oriented or other society

groups.

Original Article

Food Sci. Technol, Campinas, v42, e94321, 20222

Surveillance for foodborne diseases

2013). In 2009, the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA)

set up the FBDs surveillance system to ensure food safety and

prevent unnecessary foodborne illnesses. is included checking

for pathogenic microorganisms, food products and plants entering

the food supply, and chemical contamination (Wuetal., 2018).

e system monitored FBDs cases, outbreaks and suspected risk

factors to identify potential hazards. Zhejiang Province started the

FBDs surveillance system in 2010. To date, 31 major surveillance

hospitals are involved. e Aliated Jinhua Hospital, Zhejiang

University School of Medicine, as the biggest sentinel hospital

in midwest Zhejiang, is among them.

Previous literature shows there were few studies from the

perspective of hospitals. e objective of this study is to describe

the demographic and epidemiological characteristics of FBDs

surveillance carried out by Aliated Jinhua Hospital, Zhejiang

University School of Medicine during 2016–2019. Furthermore,

it provided several recommendations for policy perfection and

cooperation between hospitals and centres for disease control

and prevention (CDC).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Case denition

FBDs cases are dened as patients with diarrhoea (frequency

equal or greater than three instances of abnormal stool characters)

or vomiting or toxic symptoms suspected of being caused by food

consumption. An outbreak is dened as two or more patients

with FBDs who consumed the same food prior to the onset of

illness at a similar time, and the clinical manifestations of all

poisoned patients are basically similar.

2.2 Data sources

We collected and summarised data through the CFDA’s

surveillance system. 2,919 FBDs cases were selected in a sentinel

hospital in Jinhua city from 2016–2019, and 1,651 (56.56%) were

male, while 1,268 (43.44%) were female. e information was

collected for the number of outpatients and patients hospitalised

due to diarrhoea. Each patient’s details included gender, age,

occupation, home address, contact information, diet, duration

of disease, clinical symptoms of illness, suspected food vehicle,

setting of food preparation or consumption and the number of

cases by suspected causative hazards. Stool samples (only from

patients with diarrhoea) were collected and sent to the laboratory

for conrmation, and they are mainly detected by bacterial

culture and molecular biology. All the laboratory examination

methods were executed in accordance with national standards

(GB47894-2010, GB47895-2003, GB47897-2008 and GB47896-

2003) and the testing procedures specied in e Manual of

2014 National Foodborne Disease Monitoring Work.

2.3 Food vehicle classication

Food vehicles were combined into nine classications for

clarity. For example, meat products and aquatic animal products

were included in animal foods. Vegetable products, fruit products

and fungi products were included in plant foods. Multiple foods

refer to consuming two or more classications of foods. Blended

foods refer to a mixture of two or more classications of foods,

such as dumplings.

2.4 Data analysis

2,919 FBDs cases were derived from the CFDA surveillance

system. SPSS12.0 were used to carry out descriptive analysis of

numerical variables, frequency and composition ratio analysis

of categorical variables.

3 Results

3.1 Demographic distribution

Of 2,919 FBDs cases from 2016–2019, 2,480 cases reported

suspected food. e 0~, 16~ and 26~ age group had higher

percentages. Students and farmers are high risk groups of food

poisoning, accounting for 41.49% and 22.85% of the total cases,

respectively. (Table1).

3.2 Time distribution

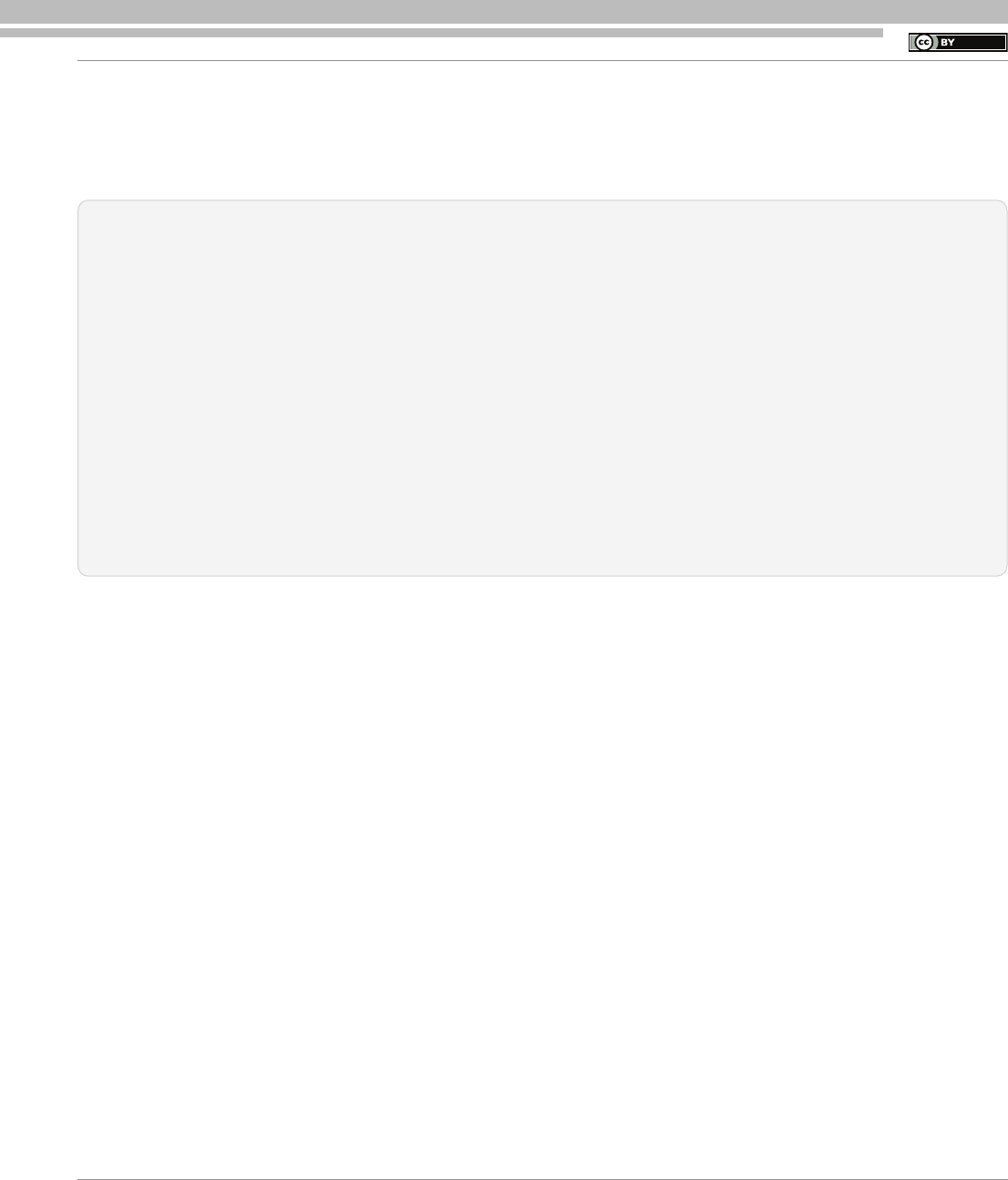

e months of August (398, 13.63%), September (333, 11.41%)

and July (330, 11.31%) accounted for most cases. e fewest

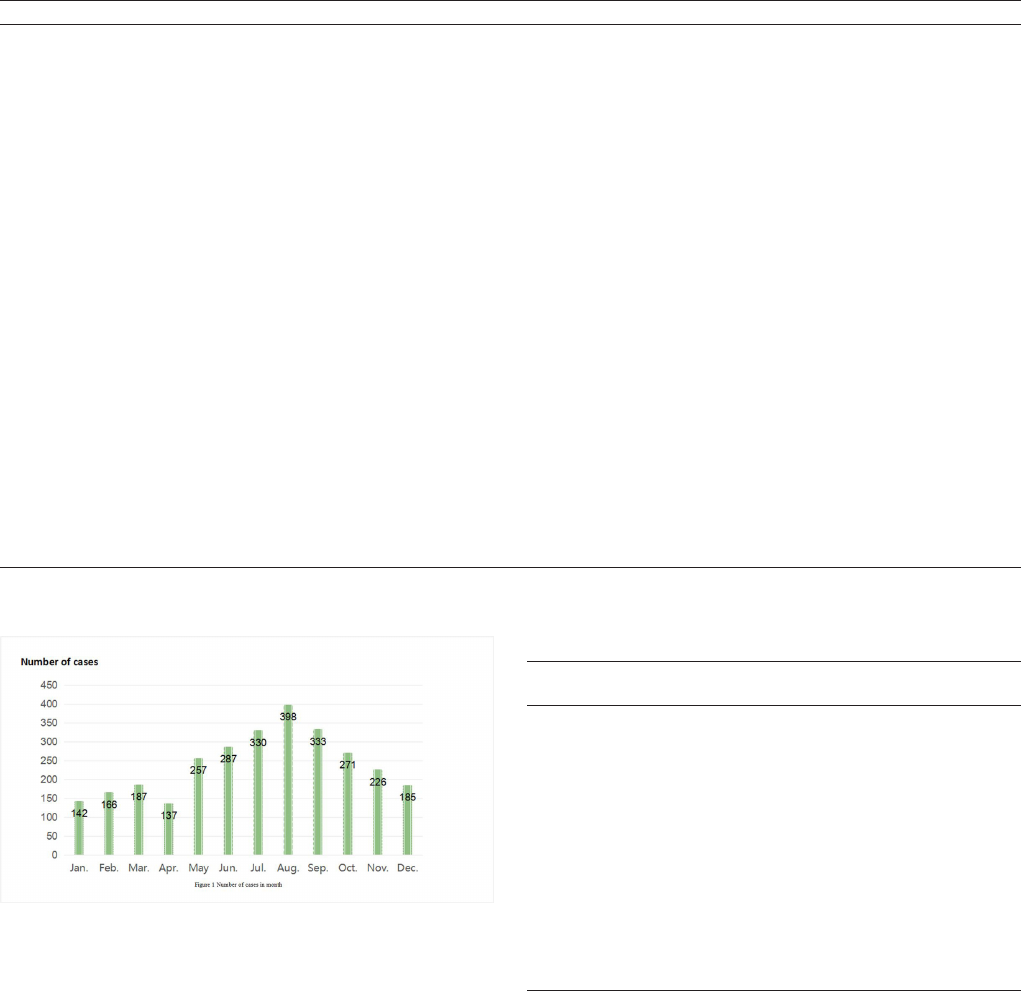

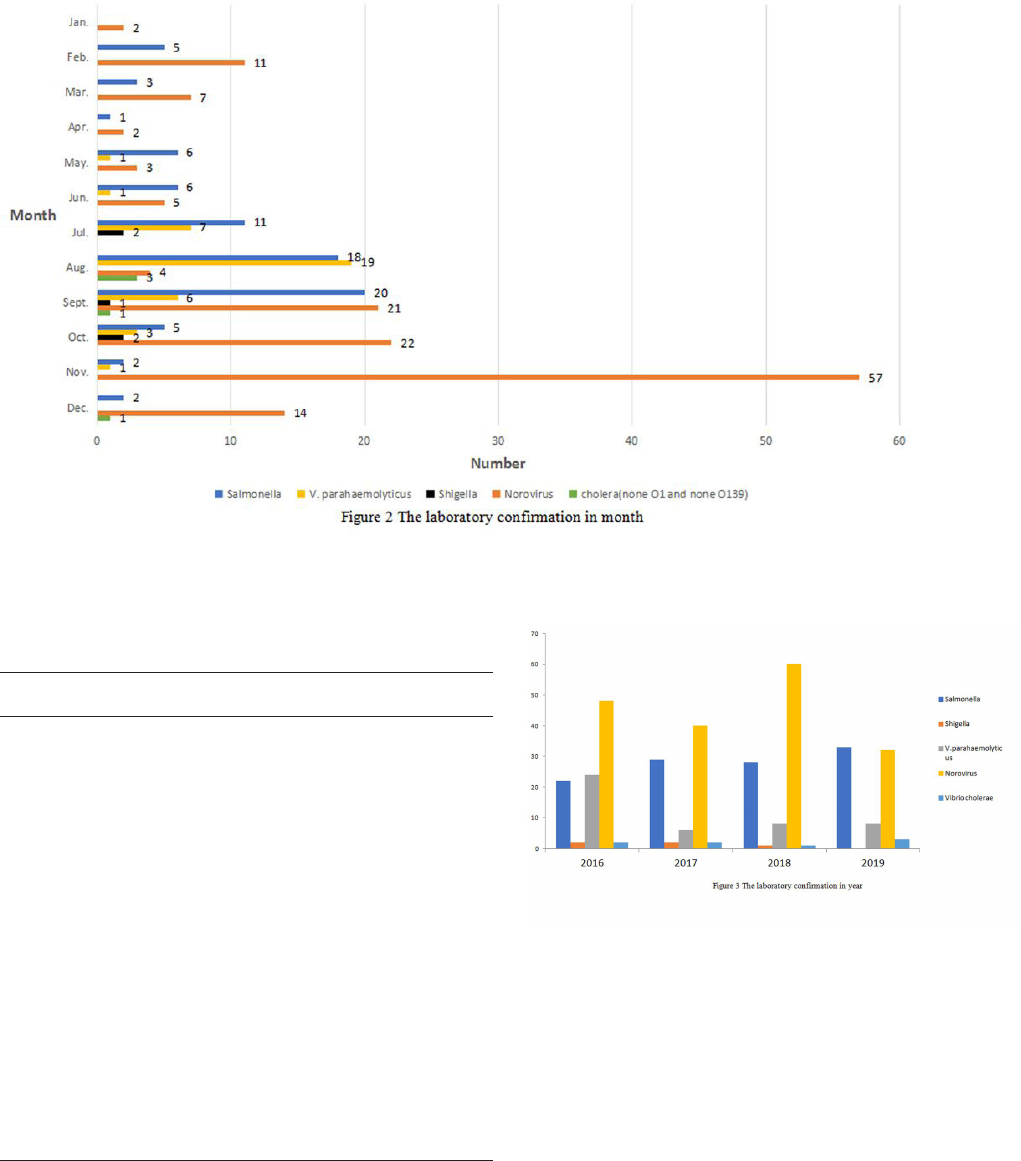

cases occurred in the January to April period (Figure1). e two

most frequent pathogens supported by laboratory conrmation

are Norovirus and Salmonella (Figure2and3).

3.3 Number of patients and hospital admissions due to

diarrhoea

From 2016–2019, the number of outpatients suering

from diarrhoea made up an average of 0.67% (0.53%–0.87%)

of the total patients. e number of patients hospitalised due to

diarrhoea made up an average of 0.53% (0.38%–0.74%) of the

total hospitalised patients.

3.4 Main clinical symptoms of illness

e major symptoms of illness were diarrhoea (97.64%),

fever (27.95%), abdominal pain (24.67%), vomiting (22.30%),

and nausea (13.7%). e clinical symptoms of cases are shown

in detail in Table 2 and Figure 4.

3.5 Setting of food preparation or consumption, and

suspected food vehicles

Of 2,919 FBDs cases, 2,480 patients were willing or able to

provide information about food consumption in terms of food

processing and packaging methods. Catering services accounted

for 979 cases (39.48%). Homemade food was the second most

common method, accounting for 840 cases (33.87%), followed

by bulk food (273 cases, 11.01%), other methods (229 cases,

9.23%) and prepackaging (159 cases, 6.41%). Nine food

classications were detected. e top ve were animal foods

(798 cases, 32.18%), multiple foods (405 cases, 16.33%), plant

foods (369 cases, 14.88%), milk and beans (263 cases, 10.60%)

and others, mainly including lactation of human milk (303 cases,

12.22%) (Table3).

Original Article

Xu; Yang

Food Sci. Technol, Campinas, v42, e94321, 2022 3

3.6 Causative hazards

e causative hazards were classied into infectious and

cases of intoxication. With decreased immunity, the human body

produces less antibody synthesis. is enhances the number of

infectious cases. Poisoning cases occurred due to misuse of toxic

wild mushrooms and herbs or misuse of pesticides. Consuming

wild mushrooms resulted in the majority of cases of intoxication

and outbreaks (Table4).

4 Discussion

From 2001 to 2010, 5,021 outbreaks of FBDs were reported

in China, causing 140,101 illnesses and 1,427 deaths (Lietal.,

2018). FBDs cause a huge burden of disease globally, especially

in less developed countries. As a typical developing country,

China’s economy has developed rapidly since the reform and

opening period. However, public health systems like food safety

surveillance in China did not improve until the outbreak of

SARS in 2002, which posed serious challenges. e food safety

incidents mentioned above have not only heavily damaged

China’s food industry and exports but also done serious harm

to its national reputation and international image. Worryingly,

the more serious accompanying negative eects have not been

completely eliminated.

Table 1. Demographic distribution of foodborne disease cases.

Classication Number of cases Percent(%) Classication Number of cases Percent(%)

Gender Year

Male 1651 56.56 2016 923 31.62

Female 1268 43.44 2017 732 25.08

Age group(yr.) 2018 677 23.19

0~ 732 25.08 2019 587 20.11

6~ 260 8.91

16~ 367 12.57

26~ 367 12.57

36~ 253 8.67

46~ 304 10.41

56~ 309 10.59

66~ 327 11.20

Occupation

Students(include

preschoolers)

1211 41.49

Farmers 667 22.85

Oce sta 310 10.62

Workers 283 9.70

Commercial service 275 9.42

Unemployed 146 5.00

Catering services 10 0.34

Other 17 0.58

Tot a l 2919 100 Tot a l 2919 100

Figure 1. Number of cases in month.

Table 2. Clinical symptoms of foodborne disease cases.

Main clinical

symptoms

Number of cases Rate(%)

Diarrhea 2850 97.64

Fever 816 27.95

Abdominal pain 720 24.67

Vomiting 651 22.3

Nausea 400 13.7

Hypourocrinia 138 4.73

irst 61 2.09

Dehydration 49 1.68

Wea k ness 36 1.23

Tic 30 1.03

Chills 29 0.99

Convulsions 15 0.51

Original Article

Food Sci. Technol, Campinas, v42, e94321, 20224

Surveillance for foodborne diseases

In our study, the patients’ symptoms are mainly diarrhoea,

fever, abdominal pain, vomiting and nausea, as shown in other

studies. Infectious cases usually have digestive symptoms of

diarrhoea, abdominal pain or vomiting. As the leading symptom

of FBDs, diarrhoeal disease is also one of the leading causes

of death in children under ve (Asefaetal., 2020). In a single

hospital like ours, within four years, 53,733 (0.67%) outpatients

seek treatment due to diarrhoea. Among these patients,

2,658 (0.57%) were hospitalised (Table2). is causes great

health and nancial burden to patients, as well as increasing

doctors’ workloads. Further, the risk of hospital infection could

be a threat to other patients.

Males were more likely to suer from FBDs, as men were

generally more adventurous than women when making irrational

decisions (Shanetal., 2019). Children under six were more likely

to suer FBDs, as mentioned in the previous study (Havelaaretal.,

2015), due to their lower immunity and the absence of health

education. Preschoolers and students accounted for more than

60% of cases. is is partly due to their lower immunity, as

Figure 2. e laboratory comrmation in month.

Figure 3. e laboratory comrmation in year.

Table 3. Number and proportion of food preparation or consumption

and vehicle.

Number of

cases

Percent(%)

Setting of food preparation or

consumption

Catering services 979 39.48

Homemade 840 33.87

Bulk food 273 11.01

Prepackaging 159 6.41

Else ( lactation of human milk, etc) 229 9.23

Suspected food vehicle

Animal foods 798 32.18

Multiple foods 405 16.33

Plant foods 369 14.88

Milk and bean 263 10.6

Blended foods 143 5.77

Cereals 95 3.83

Drinks 75 3.02

infant foods 29 1.17

Else(Sweetmeat, Nut, condiment, Algae,

etc)

303 12.22

Tot a l 2480 100

Original Article

Xu; Yang

Food Sci. Technol, Campinas, v42, e94321, 2022 5

mentioned above. is is also due to their lack of control over

their diets and the likelihood that they consume food at roadside

stands which usually have poor sanitary conditions. Signicantly,

farmers made up a h of all cases. Compared with developed

countries, most farmers in China belong to a low-income group.

erefore, they pay little attention to the food safety and hygiene

and consumption settings and, thus, are more likely to be invaded

by pathogens through contaminated food.

e seasonality of FBDs cases was observed in this study.

Most cases occurred in warm months (May to October), peaking

in summer. is was in line with other studies (Wu etal.,

2021;Lietal., 2018). On the one hand, high temperatures are

conducive to pathogen growth, as is known (Yangetal., 2019).

On the other hand, insects such as ies multiply rapidly when

the temperature is appropriate, and pathogens spread to many

places, along with those hosts’ movements. As showed in Figure2,

bacteria like Salmonella, V. parahaemolyticus, Shigella and

cholera (none O1 and none O139) were commonly detected

in warm months. However, a seasonal peak in summer does

not occur for some pathogens. For instance, Norovirus is more

frequent in winter months when the temperature is relatively

low (Halletal., 2012). Certainly, temperatures are not the only

factors with seasonality. Humidity, light or other climatic factors

could also inuence pathogen growth (Parketal., 2018).

Causative hazards will invade food during each link of

preservation and processing, such as food storage, food preparation,

cooking, the cooking environment, the hand hygiene of cooks

and pantry helpers and tableware disinfecting (Yangetal.,

2019;Brownetal., 2017). One well-known person was ‘Typhoid

Mary’ who brought typhoid to places where she worked as a

cook (Fegan & Jenson, 2018). About 40% of patients with FBDs

reported consuming food from catering service settings prior to

the onset of illness. In recent years, it has become fashionable

to order takeaway food through apps. is brings more unsafe

factors since it is dicult to supervise the quality of food and the

preparation process for those without xed shops. In addition,

due to the complexity of Chinese food and cooking methods,

pathogens could contaminate foods in more ways, making it

dicult to avoid FBDs. e main food vehicles suspected of

causing illnesses are animal foods and multiple foods. As it is

known, animal foods can provide hotbeds for pathogens if not

stored properly and, thus, cause diseases (Marr, 1999). Similar

to other studies (Wuetal., 2019;Fingeretal., 2019), multiple

foods remain one of the most common vehicles, and this presents

diculties in identifying the specic foods and preventing them

from circulation. It should be noted that homemade foods led

to more than 30% of cases. As shown above, 1.48% of FBDs

cases and 20% of the FBDs outbreaks related to people picking

wild mushrooms, herb or agaric and consuming them at home,

even consuming pesticide by mistake. All of this suggested the

absence of food safety education for the general public.

With globalisation, the problems of food safety will not

be restricted to a single country or region. In China, a large

population, environmental pollution, regional development

imbalances and public health system construction remain

crucial. Challenges are upon us, not merely to hospitals but also

government agencies, CDC, health supervision agencies and

food enterprises. Government agencies must reinforce laws to

strengthen food safety. Hospitals should be on the alert for FBDs

cases, provide proper treatment and share information with CDC

as well as other health supervision agencies or organisations.

As the source of the food supply chain, food enterprises must

stick to the rules and regulation on food safety and hygiene to

make people safe.

Some limitations exist in this study. First, we did not use any

sequencing or genomic methodologies. e use of the power

of whole genome sequencing in combination with laboratory

methods in order to understand genetic dierences between

pathogens and to conduct surveillance of diseases. Second, a few

patients failed to provide information about food consumption.

It reduced the available data of food consumption characters

to a degree. ird, when considering dierent diagnostic levels

and a lack of laboratory conrmation, a small number of cases

that might not be classied as FBDs were included in the study.

ese cases may provide some interference information for

analysis. Fourthly, this study was conducted in only one hospital.

In the future, we hope more hospitals in Jinhua city will join the

surveillance system. e data from each hospital will be combined

and be more representative of the whole city. Finally, only a few

pathogens were identied by the laboratory for conrmation,

resulting in some pathogens not being detected. We hope that in

future, more pathogens will be included and that this will improve

the rate of laboratory conrmation. us, suggestions from

studies will be more targeted for policymakers and supervisors.

In these future studies, we will make improvements according

to the above limitations.

Table 4. Number of cases by suspected causative hazards.

Causative hazards Number of cases Percent(%)

Infectious cases 2876 98.52

Toxic cases 43 1.48

Wild mushrooms 28 0.96

Herb 11 0.38

Agaric 2 0.07

Pesticide 2 0.07

Figure 4. Pathogen constituents.

Original Article

Food Sci. Technol, Campinas, v42, e94321, 20226

Surveillance for foodborne diseases

Fegan, N., & Jenson, I. (2018). The role of meat in foodborne disease: Is

there a coming revolution in risk assessment and management? Meat

Science, 144, 22-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.04.018.

PMid:29716760.

Finger, J. A. F. F., Baroni, W. S. G. V., Maffei, D. F., Bastos, D. H. M., &

Pinto, U. M. (2019). Overview of foodborne disease outbreaks in

Brazil from 2000 to 2018. Foods, 8(10), 434. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/

foods8100434. PMid:31547589.

Fu, P., Wang, L. S., Chen, J., Bai, G. D., Xu, L. Z., & Guo, Y. C. (2019).

Analysis of foodborne disease outbreaks in China mainland in 2015.

Zhongguo Shipin Weisheng Zazhi, 31(01), 64-70.

Fung, F., Wang, H. S., & Menon, S. M. (2018). Food safety in the 21st

century. Biomedical Journal, 41(2), 88-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.

bj.2018.03.003. PMid:29866604.

Guo, S., Lin, D., Wang, L. L., & Hu, H. (2018). Monitoring the results

of foodborne diseases in Sentinel Hospitals in Wenzhou city, China

from 2014 to 2015. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 47(5), 674-681.

PMid:29922609.

Hall, A. J., Eisenbart, V. G., Etingüe, A. L., Gould, L. H., Lopman, B.

A., & Parashar, U. D. (2012). Epidemiology of foodborne norovirus

outbreaks, United States, 2001-2008. Emerging Infectious Diseases,

18(10), 1566-1573. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1810.120833.

PMid:23017158.

Havelaar, A. H., Kirk, M. D., Torgerson, P. R., Gibb, H. J., Hald, T.,

Lake, R. J., Praet, N., Bellinger, D. C., Silva, N. R., Gargouri, N.,

Speybroeck, N., Cawthorne, A., Mathers, C., Stein, C., Angulo, F.

J., & Devleesschauwer, B. (2015). World Health Organization global

estimates and regional comparisons of the burden of foodborne

disease in 2010. PLoS Medicine, 12(12), e1001923. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001923. PMid:26633896.

Hu, D. W., Liu, C. X., Zhao, H. B., Ren, D. X., Zheng, X. D., & Chen,

W. (2019). Systematic study of the quality and safety of chilled pork

from wet markets, supermarkets, and online markets in China.

Journal of Zhejiang University Science B., 20(1), 95-104. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1631/jzus.B1800273. PMid:30614233.

Lam, H. M., Remais, J., Fung, M. C., Xu, L. Q., & Sun, S. S. M. (2013).

Food supply and food safety issues in China. Lancet, 381(9882),

2044-2053. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60776-X.

PMid:23746904.

Li, Y. Q., Huang, Y. L., Yang, J. J., Liu, Z. H., Li, Y. M., Yao, X. T., Wei, B.,

Tang, Z. Z., Chen, S. D., Liu, D. C., Hu, Z., Liu, J. J., Meng, Z. H., Nie,

S. F., & Yang, X. B. (2018). Bacteria and poisonous plants were the

primary causative hazards of foodborne disease outbreak: a seven-

year survey from Guangxi, South China. BMC Public Health, 18(1),

519. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5429-2. PMid:29669556.

Liu, J. K., Bai, L., Li, W. W., Han, H. H., Fu, P., Ma, X. C., Bi, Z. W., Yang,

X. R., Zhang, X. L., Zhen, S. Q., Deng, X. L., Liu, X. M., & Guo, Y.

C. (2018). Trends of foodborne diseases in China: lessons from

laboratory-based surveillance since 2011. Frontiers of Medicine, 12(1),

48-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11684-017-0608-6. PMid:29282610.

Marr, J. S. (1999). Typhoid mary. Lancet, 353(9165), 1714. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)77031-8. PMid:10335825.

Park, M. S., Park, K. H., & Bahk, G. J. (2018). Interrelationships

between Multiple Climatic Factors and Incidence of Foodborne

Diseases. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public

Health, 15(11), 2482. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112482.

PMid:30405044.

Shan, L., Wang, S. S., Wu, L. H., & Tsai, F. S. (2019). Cognitive biases

of consumers’ risk perception of foodborne diseases in China:

examining anchoring effect. International Journal of Environmental

is study revealed epidemiological characteristics of

FBDs in our hospital and identied some higher risk factors for

interventions. is study revealed epidemiological characteristics

of FBDs and identied some higher risk factors for interventions.

Males and preschool children were more likely to suer FBDs.

Salmonella and Norovirus were the main pathogens. Foods from

catering services settings and animal foods were the factors that

most oen contribute to foodborne diseases. Most of the cases

of intoxication and outbreaks were related to wild mushrooms.

Some information was provided to the government and other

organisations for further policy-making and supervision to

ensure food safety.

Ethical approval

e study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration

of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Aliated Jinhua Hospital, Zhejiang University

School of Medicine (2019-301).

Conict of interest

e authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and material

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included

in this published article.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author contribuitions

ese authors contributed equally to this study.

Acknowledgements

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or

publication of this article.

References

Asefa, A., Qanche, Q., Asaye, Z., & Abebe, L. (2020). Determinants

of delayed treatment-seeking for childhood diarrheal diseases in

Southwest Ethiopia: a case-control study. Pediatric Health, Medicine

and erapeutics, 11, 171-178. http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/PHMT.

S257804. PMid:32607050.

Brown, L. G., Hoover, E. R., Selman, C. A., Coleman, E. W., & Rogers,

H. S. (2017). Outbreak characteristics associated with identification

of contributing factors to foodborne illness outbreaks. Epidemiology

and Infection, 145(11), 2254-2262. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/

S0950268817001406. PMid:28689510.

Chen, J. S. (2016). Who is the number one enemy of food safety?.

Dietetic Science, 2016(5), 20.

El-Nezami, H., Tam, P. K. H., Chan, Y., Lau, A. S. Y., Leung, F. C. C.,

Chen, S. F., Lan, L. C. L., & Wang, M. F. (2013). Impact of melamine-

tainted milk on foetal kidneys and disease development later in life.

Hong Kong Medical Journal, 19(Suppl 8), 34-38. PMid:24473527.

Original Article

Xu; Yang

Food Sci. Technol, Campinas, v42, e94321, 2022 7

Epidemiology of foodborne disease outbreaks from 2011 to 2016 in

Shandong Province, China. Medicine, 97(45), e13142. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1097/MD.0000000000013142. PMid:30407341.

Wu, X., & Xu, D., Ji, L., Zha, Y., & Chen, L. (2021). Surveillance results

of foodborne diseases in Huzhou, Zhejiang, 2018–2020. Disease

Surveillance, 36(9), 958-962.

Yang, L., Sun, Y. B., Zhong, Q., Duan, D. S., Liu, S. Q., & Zhang, Y.

(2019). Epidemiological characteristics and spatio-temporal patterns

of foodborne diseases in Jinan, Northern China. Biomedical and

Environmental Sciences, 32(4), 309-313. PMid:31217068.

Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2268. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/

ijerph16132268. PMid:31252539.

Wu, G., Wang, L. S., Wang, Q., Han, R., Zhao, J. S., Chu, Z. H., Zhuang,

M. Q., Zhang, Y. X., Wang, K. B., Xiao, P. R., Liu, Y., & Du, Z. J. (2019).

Descriptive study of foodborne disease using case monitoring data

in Shandong province, China, 2016-2017. Iranian Journal of Public

Health, 48(4), 722-729. http://dx.doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v48i4.1006.

PMid:31110983.

Wu, G., Yuan, Q., Wang, L. S., Zhao, J. S., Chu, Z. H., Zhuang, M. Q.,

Zhang, Y. X., Wang, K. B., Xiao, P. R., Liu, Y., & Du, Z. J. (2018).

Original Article